Bail reform failed at the Texas Legislature this year, but litigation pending against Harris County may still dramatically alter the landscape regarding judges making pretrial detention decisions based on the ability to pay. (Grits interviewed one of the litigants, Texas Fair Defense Project Executive Director Becky Bernhardt, when the litigation launched last fall.)

Harris County lost Round One in federal district court. While we wait to see what the 5th Circuit thinks about that case, the action on bail reform shifts to New Jersey, where Gov. Chris Christie signed comprehensive bail reform into law last year. The bail bond industry is hitting back hard. See coverage from the NY Times and NBC News.

Reform opponents including the Texas District and County Attorney Association Twitter feed have been touting this case as an example of the failures of risk-assessment systems. In that episode in San Francisco, a court employee entered mistaken data into a risk assessment developed by Texas' Laura and John Arnold Foundation and a released inmate committed a murder.

That is indeed a terrible tragedy. But if a court employee entered flawed data, that's hardly an indictment of the tool. Moreover, nobody said the risk assessment system will never make mistakes, only that it will make FEWER mistakes than human jurists. In the end, flaws in either system can only be judged by answering the question, "Relative to what?"

These are vast human systems prone to error at the margins. Based on various studies by academics and practitioners, Grits has estimated in the past that perhaps 1.5 to 2.5 percent of TDCJ inmates at any given time are actually innocent people falsely convicted. Some of them, like Timothy Cole or Carlos De Luna, may die before they're exonerated. And where there are false positives, there are also false negatives, where people should have been jailed but aren't. In extreme cases, some of them will take the additional opportunity to commit murder. We're talking about an error-ridden system with a change-resistant culture.

But because both risk-based and bail systems can generate errors, the question becomes, "which is more erroneous?" And the answer is the money bail system by a country mile.

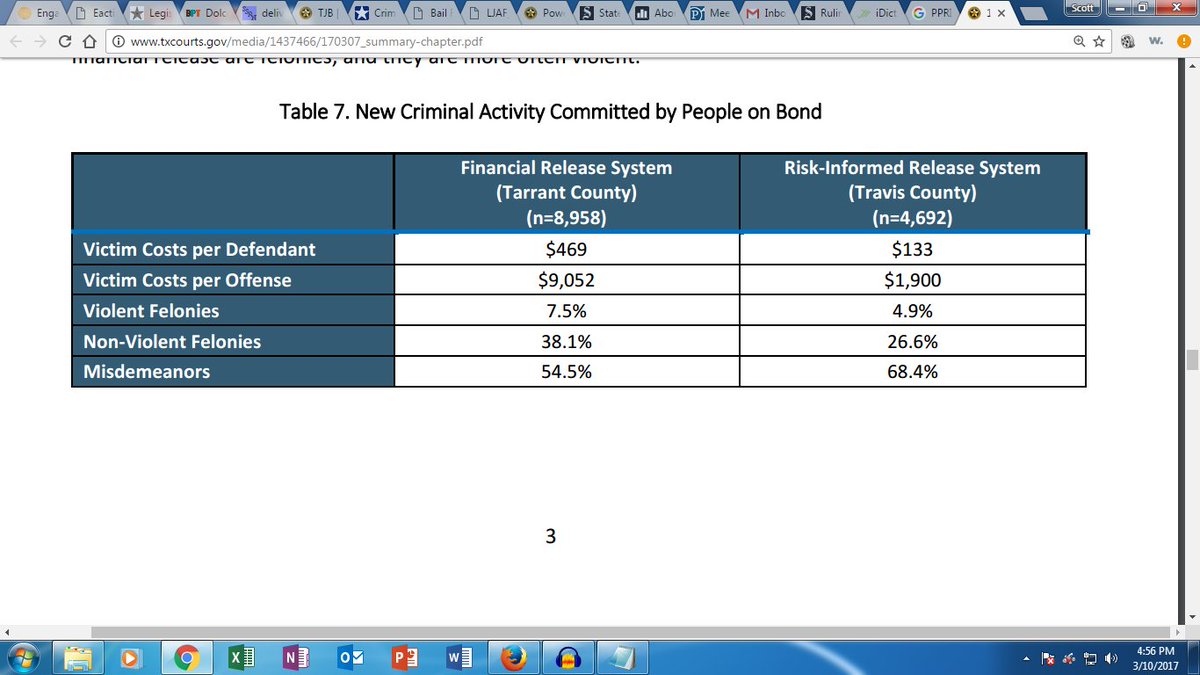

A study out of Texas A&M comparing Tarrant County's money bail system to a risk-based system in Travis County found that 7.5 percent of those released on bail committed a violent felony while they were out compared to 4.9 percent under a risk-based system. Victim costs were also much lower under the risk-based system.

Page 50 of that report includes a table with more detail. Under Tarrant's money-bail system, 4.6 percent of those out on bail allegedly committed a violent assaultive offense, compared to 3.6 percent under a risk-based system. Similarly, 2.1 percent released on bail in Tarrant allegedly committed robberies, compared to 0.8 percent in Travis. So the risk assessment system doesn't always identify potential problems, but it does a better job than human judges.

To the point of the case out of San Francisco involving the Arnold Foundation risk assessment, the A&M study found that 0.2 percent of defendants released on money-bail in Tarrant during this period committed homicides, compared to 0.0 percent in Travis. That's about 18 murders over the 3.5 year period studied, which for the record is more than zero.

But, even if there had been a homicide or two committed by pretrial releasees in Travis County under the risk assessment model, any criticism must be couched in some context: Compared to what? Are we judging based on a comparison to outcomes under the money-bail status quo, which are much worse? Or are we comparing to some Platonic ideal/fantasy where no one released pretrial ever commits a new offense or fails to show up for court? Every system looks terrible compared to the fantasy. But if we're picking the best among real-world options, errors under the risk assessment model are more tolerable.

If one murder by a pretrial releasee is hyped by reality TV stars and heavily covered by the media, while 18 murders under the money bail system in a single Texas county get no coverage at all, that doesn't mean all the problems lie on the risk assessment side. It just means the bail-bond side is more adroit than reformers at PR.

A risk assessment tool does what it says, assesses risk. It does not eliminate risk. And it is not a crystal ball. Moreover, as they're implemented, tools should and inevitably will be constantly evaluated and tweaked to improve performance. We're at the beginning of this conversation, neither the Arnold Foundation assessment nor any other represents the last word on what these tools will finally look like.

But even at these early stages, it's possible to identify and dismiss disingenuous and self-interested criticisms, particularly those which ask us to judge risk-assessment errors in a context-free environment. When confronting a problem as decentralized, vast, and flawed as American mass incarceration, it's important not to allow the perfect to become the enemy of the good.

It's a point in fact that people who are innocent are less likely to be wrongly convicted if they are released prior to the tril.

ReplyDeleteGrits, the bail bonds crowd are already circulating "Willie Horton" horror stories, just too much money at stake for them to admit changes are needed.

ReplyDelete