|

| Source: TCJC Twitter feed. |

During the 17-25 year old period, and particularly before age 21, neuroscientists now understand that young brains have yet to finish developing, especially as it relates to cognitive reasoning and impulse control. And some national experts have persuasively argued that the justice system needs to more effectively accommodate those differences in brain function.

So, in that vein, Grits was interested in this story out of the Phildadelphia Inquirer (9/7) detailing the fates of 70 released murderers who committed their crimes as young men and women. Like the defendant in Kentucky, they had served sentences for heinous crimes committed when they were teenagers. But they are now being released some two generations later. Here's how the story opened:

For the first time in a generation, Pennsylvania prisons are releasing convicted murderers by the dozen.

In the last year, 70 men and women — all locked away as teens — have quietly returned to the community after decades behind bars. They're landing their first jobs, as grocery store cashiers and line cooks, addiction counselors and paralegals. They are, in their 50s and 60s, learning to drive, renting their first apartments, trying to establish credit, and navigating unfamiliar relationships. They're encountering the mismatch between long-held daydreams and the hard realities of daily life.

These are the first of 517 juvenile lifers in Pennsylvania, the largest such contingent in the nation, to be resentenced and released on parole since the Supreme Court decided that mandatory life-without-parole sentences for minors are unconstitutional.The struggles facing these parolees perhaps are to be expected. If you'd been incarcerated since Smokey and the Bandit was in theaters, you'd face difficulty adjusting to 21st century America, as well. Regardless, "So far, not one of the 70 has violated parole."

Perhaps that should be expected, too. As it happens, murderers have among the lowest recidivism rates. And the judge out of Kentucky whom we discussed in our podcast cited this study in his ruling to say that, "ninety (90) percent of serious juvenile offenders age out of crime and do not continue criminal behavior into adulthood."

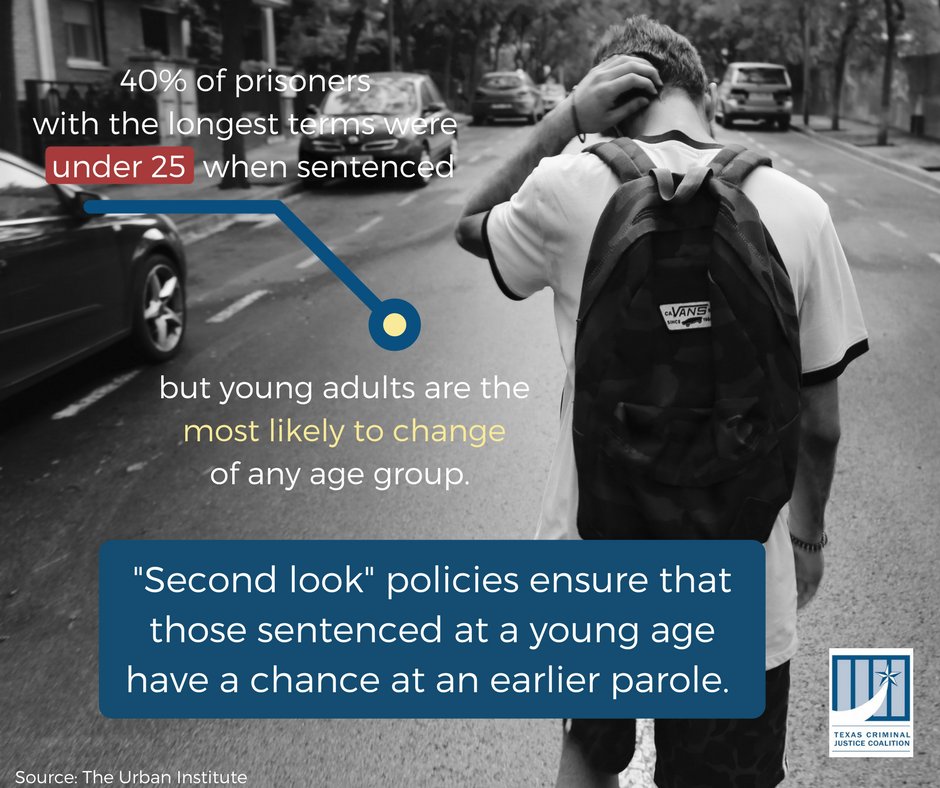

This represents a lot of folks. This summer, the Urban Institute issued a study which, the Marshall Project reported, found that two out of five inmates serving very long sentences committed their crimes before age 25. (See Grits' earlier discussion.)

There are a few different ways one could take into account these differences in youthful brain chemistry, and likely more Grits hasn't considered yet. My old pal Vinnie Schiraldi has suggested creating a separate third system to deal with 18-25 year olds (it'd be 17-25 in Texas, where we have not yet raise the age of adult culpability to 18). Elsewhere, some states like Connecticut are considering expanding their juvenile justice system to cover offenders up to age 21. Alternatively, Schiraldi has privately suggested to Grits that perhaps certain enhancements, barriers to reentry, etc., could be eliminated or reduced for younger offenders since their likelihood of rehabilitation is so much higher.

I'm sure there are other ways to skin this cat. We're on the front end of a national conversation about these topics spurred by recent scientific advancements. The suggestions for how to accommodate this new information remain prefatory and barely formed. But over time, as scientists better understand the human brain - and as the justice system slowly but surely adapts that knowledge to inform its various functions - it's not difficult to imagine major implications for these observations about brain development in a justice system based on identifying and punishing bad decisions, even if we can't say for sure what they'll be yet.

That said, inevitably, someone's parole will be revoked among this Pennsylvania cohort. The road to reentry is too difficult (as this article effectively described) and the array of humanity caught up in the system is too diverse for it to never happen. But prisoners who've served decades until they're now old men (and to a less common extent, women), especially if they had good behavior records while inside, are remarkably safe release risks compared to many younger inmates convicted of less serious offenses.

And not a single word regarding the victims and their survivors. I guess they just don't matter do they?

ReplyDeleteIf the topic is the "rehabilitation potential for teen killers," what would you have me say about victims and their survivors? Merely that they exist? Should I mention them just as a genuflection, so you can check it off some imaginary list of victim affirmations? If that's all you want, you're too easily satisfied.

ReplyDeleteIf you're complaining that the system doesn't meet the needs of victims and survivors, I'm 100% with you and we could discuss the whys and wherefores all day. But if you're pretending that somehow extending the most extreme prison sentences past four decades for offenders who committed their crimes under age 25 benefits survivors in some specific way (no way at that point to benefit victims), you'd have to articulate exactly what that is. I don't see it, which is why I didn't mention it.

Grits, you didn't comment on global warming or ethnic poverty either. Lets just toss it all in there so the trolls won't have anything to complain about. Oh, wait a minute . . . They're trolls. That's what they do - tear down and complain. Carry on, Grits; carry on.

ReplyDelete