Grits is broadly sympathetic to the much-ballyhooed claim (championed most prominently by the Texas Association of Counties) that Texas state government unfairly cost shifts to county and municipal governments via "unfunded mandates." But critics of unfunded mandates are wrong to include indigent defense in the "unfunded mandate" critique and are only doing so by ignoring the real and much more costly "unfunded mandates" running in the other direction.

In the Waco Tribune Herald, McLennan County Precinct 4 Commissioner Ben Perry articulated the oft-heard complaint:

Indigent defenses expenses are a good example of an unfunded mandate forced on counties, Perry said.

The state once covered the costs of providing legal representation for people accused of crimes who cannot afford adequate defense, as required by the U.S. Constitution. But the state has been reducing its contribution for years.

The county has almost $4.7 million budgeted for indigent defense this year, up from $4.1 million in 2014.

That includes $270,000 in state money this year, down from $532,000 in 2014.

The Texas Fair Defense Act of 2001 does not include a way to pay for its requirements, shifting the expenses to county taxpayers, the county’s resolution states. Statewide spending on indigent defense in 2016 was more than 2.7 times as much as it was when the act passed, according to the Texas Association of Counties.

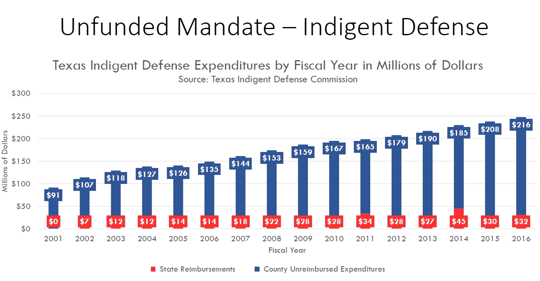

The state spent $247.4 million in 2016, up from $91.4 million in 2001.The second paragraph in that pull quote is just a lie. There has never been a time when the state paid for all indigent defense costs in Texas; it was entirely a county-level responsibility until after the new millenium. The article itself includes a graphic demonstrating that claim is false:

Notice the state contribution in 2001 was $0. The state began to put in MORE money after the Fair Defense Act, not less. Moreover, the majority of the increase at the county level may be accounted for by inflation and population growth.

The big (unstated above) problem is that, before the Fair Defense Act, counties simply didn't comply with their obligations to appoint counsel, especially in misdemeanor cases. That was, indeed, cheaper. In many counties, when the Fair Defense Act passed, no misdemeanor defendants were appointed counsel - zero, zilch, nada. Now, appointment rates often approach 50 percent, not great but better. You can blame the state for making the locals comply with the constitution, if you prefer to deprive defendants of their 6th Amendment right to counsel to save a buck. But that doesn't make this an unfunded mandate, any more than it's an unfunded mandate to require counties to pay for local prosecutors.

The volume of indigent defense services required is largely a function of local decisions and priorities, so if the DA's office is still prosecuting lots of penny ante cases even after crime has declined for two decades, locals should foot the bill for those defense costs.

The flip side of this "unfunded mandate" argument are the un-discussed unfunded mandates to the state. McLennan County has a reputation for securing tougher-than-typical plea bargains, but state taxpayers must pick up the tab for high incarceration rates and longer sentences. And those costs are FAR greater than the costs for those prisoners' lawyers.

Grits has long believed the Lege should offer the Texas Association of Counties a deal on indigent defense: The state picks up the full indigent defense tab, and counties pay to incarcerate every defendant they send to TDCJ for the whole time they're inside. Then everything would be "fair."

Except that "fair," as I frequently tell my granddaughter, is a place where they judge pigs. It doesn't generally have much to do with the Texas justice system, and certainly not with how it's financed.

RELATED: If crime is down, asks legislator, why are indigent defense costs rising?

ALSO RELATED: 'Cap and Trade' proposal could end mass incarceration

RELATED: If crime is down, asks legislator, why are indigent defense costs rising?

ALSO RELATED: 'Cap and Trade' proposal could end mass incarceration

Once upon a time nearly all 'justice" was handled at the local level throughout Texas. Don't know if you happened to see 60 Minutes last Sunday with the segment Oprah Winfrey did on the legacy of lynchings throughout the nation, but Texas was certainly not immune from this practice. I get the quid pro quo you're suggesting with swapping indigent defense costs for incarceration costs, but I'm afraid the consequences of any such plan would simply be a return to vigilante justice in those counties which didn't have the resources to send their criminals to prison. Are you willing to also give up state oversight of county jails and other forms of local punishment (penal farms? chain gangs?) in your proposal? As long as we're negotiating the state's abandonment of its role in the correctional system, we might as well put everything on the table, right?

ReplyDelete@6:46, jail regulation is unrelated to indigent defense, fwiw.

ReplyDeleteAnyway, it's county governments who hope to "abandon" their historic role in the justice system by pawning off indigent defense costs on the state. I'm just pointing out the bigger "unfunded mandates" in the other direction that they never mention. What I suggested is not a real proposal bc the counties would NEVER go for it - the unfunded costs THEY mandate to the state are many orders of magnitude greater than costs for indigent defense. So I was using the argument to make a point, not offering a politically viable suggestion.

As if the states money comes from a different pocket than the counties. Neither is a business, the money that they have to operate comes from our pockets. The argument seems trivial. Counties enforce the laws the state adopts within the sentencing guidelines provided by the state. If you don't like the outcome, change the sentencing guidelines. The larger argument regarding indigent defense seems to be missed in the discussion of who "pays for what". I would be curious to know how the use of options such as deferred adjudication have increased since the implementation of indigent defense. Are these folks getting a better deal now then they were then, or are the state taxpayers paying a lawyer a fee so the defendant can take the same plea deal they would have been offered without representation anyway? If that is the case then is not the larger issue with those representing defendants rather than counties as you cite?

ReplyDelete@Mark, the criminal justice system is vast and complex. One can critique bad arguments from the counties about funding for indigent defense without waiving the right to critique bad lawyers. This blog frequently does both, but one can't make every argument in every post.

ReplyDeleteGrits,

ReplyDeleteRead the article you referenced when it was written. Did not listen to the podcast, but the article cited "But it's also because the government is complicit in ineffective assistance by underfunding indigent defense, so there's a bit of a wink-and-a-nod arrangement for merely lazy as opposed to actively harmful representation." I don't agree that paying a lawyer more makes him do his job better. It shouldn't. If he doesn't like the fee arrangement he shouldn't take court appointments. It is logical however to advocate for more pay given the fact that to incarcerate a state jail felon for the minimum sentence costs the taxpayers 10,180. I don't agree however that it will change the quality of their representation. By the way, these same taxpayers, not only did they spend 500 dollars for defense, but they funded the prosecution and the court as well.

Re: "I don't agree that paying a lawyer more makes him do his job better. It shouldn't."

ReplyDeleteThis is false. An attorney cannot work many hours or even days on the case of a defendant for whom she's being paid $150 - not and pay for rent, groceries and law school debt.

Paying lawyers more doesn't make them more ethical. But systematically (and IMHO intentionally) underpaying them creates ethical problems at an institutional level that you are not acknowledging.

Finally, you're right that county taxpayers "funded the prosecution and the court as well." That's why it's disingenuous for the Texas Association of Counties to claim indigent defense costs are an "unfunded mandate." The deal has always been that counties pay for those costs and the state pays for (much more expensive) incarceration. Now they want the state to cover their piece, but that doesn't make it an "unfunded mandate."

Kind of a catch-22. Police officer rank and pay increases are based on the number of arrests they make, but the counties whine about losing money when they must pay attorneys to represent the poor. Perhaps the rank and pay increase of officers should be based on something besides the number of arrests they make?

ReplyDelete2 quick points: The US Supreme Court in Gideon v Wainwright required states to provide attorneys not counties. The Court wouldn’t make that requirement, that’s not our our system of govenrment was set up in the Constitution; it’s a Constitution of the Federal Government and the states. Secondly, counties and cities can’t place mandates on the state. That is not how our state constitution is set up, it flows downhill to the municipalities and counties.

ReplyDeleteUltimately taxpayers are paying for indigent defense. Not the state or the county. The question is which payment mechanism do we want to use. If it’s the county mechanism then we want to pay for it with higher property taxes, if it’s the state mechanism then we want a broader spectrum of payment mechanisms and specifically we don’t want to use property taxes because as we all know the state may not assess property taxes. {Though the state can’t assess property taxes, when the state drops their proportion of school funding, as they have been doing, they do increase the amount of property taxes that we have to pay.}

@4:01, in fact, the right to counsel in Texas was enshrined in statute four years before Gideon.

ReplyDeleteAnd you're wrong about counties placing no mandates on the state. Locals set sentences (the mandate) and the state must pay to incarcerate. That's reality, and nothing in the state constitution contradicts it.

Finally, I guess you can pretend that all of history and existing government structures don't exist and that we may debate these issues in the abstract. But that's not true once the Lege rolls around, and the future of indigent defense won't be decided on that basis. Rather, it will be decided amidst the existing structure that bifurcates state and county funding for different parts of the system. And if counties want to change the deal, IMO ALL aspects of the deal should be up for grabs.

Oh, I should mention I agree with you about school funding, and THAT's where the real debate over unfunded mandates should occur. This BS of trying to lump indigent defense into that debate is particularly weak tea and undermines the argument where counties and school districts really need to win it. I'm your ally on that if you engage in the debate honestly. Try and lump in every cost in your budget, however - even when it violates historical norms and simply shifts costs to the state - and you lose people like me who'd otherwise be with you.

ReplyDeleteTo the extent that Texas statute is in conflict with the Supreme Court ruling the statute is irrelevant so I take the Court’s ruling as controlling not Texas statute . If Texas decided to not provide indigent defense by statute it wouldn’t matter. So that responsibility is a state responsibility by my reading of the Court’s take on the issue.

ReplyDeleteOn where in law it says counties may not send mandates to the State: A county may not do anything unless the state allows it. I’m unaware of the state allowing counties to mandate anything on the State thus a county “state mandate” would be unconstitutional IMO.

On the setting sentences: when someone is prosecuted for a crime it is “State v John Doe” not ”Houston v John Doe.” Though the locals and the judiciary are administering these punishments it is the State that has decided the minimum, maximum, or discretionary amounts for the sentencing. These aren’t local sentence they are State sentences so they can’t be a local “state mandate.” And it’s not just a semantic argument there are very sound Constiutional and legal reasons why the State is the prosecuting party not the locals.

But again (and I think we agree on this point) it’s going to be paid for from one bucket or another, so the question is how much should come from the property tax bucket. I completely agree with you that everything should be up for discussion when unfunded mandates are debated. I guess I just disagree that there was a deal that counties made with the state or a historical norm that would prevent the rising costs in indigent defense from being brought up as a legitimate complaint from the locals. If there was a “deal,” the terms of the deal and the context has changed a hundred times since then so I don’t think it counts anymore. But you hit it on the head, the crux of it all is whether or not the cost should be shifted to the state or remain paid locally by property taxes.

Thanks for your time, comments and responses. If you have any other thoughts on my response please share and take the last word on it. Keep up the good work!

Anonymous,

ReplyDeleteI am curious about your thoughts surrounding the idea that a court appointed lawyer is somehow justified by not performing their job to the full extent due to the fact they are not compensated enough to "pay their bills" as posted by grits at 10:51. The constitution guarantees the right to counsel. As a taxpayer I am all for seeing that each individual gets a fair shake in court. I would even agree as a taxpayer to increase indigent defense funding, regardless of State or County, as I believe it would ultimately result in saving by reducing incarceration costs, and firmly believe in the right to be represented. What I cannot stomach however is the idea that an individual that agrees to perform a job for an agreed to amount is justified in doing sub-par work because of the pay they agreed to. 74% of felons are represented by court appointed counsel. Many of those whom have agreed to represent folks deemed indigent by courts, do not crank out the same caliber of work as they would for a client paying them directly despite the fact they are required to do that very thing. If they don't like the pay, they shouldn't have agreed to take court appointments. Thoughts.

@11:54, if politics stopped at the final page of a civics textbook, you'd be 100% right. As a practical matter in Texas politics - when we look at the reality of WHO the decision makers are (local DAs make decisions on who is prosecuted in "State v. John Doe," with local judges and [rarely] juries setting sentences) - you're simply wrong and (it seems like intentionally) obfuscating reality.

ReplyDeleteThe deal on criminal justice as long as you and I have been alive in Texas is that counties pay for what goes on in the courthouse and the state pays for what goes on at the prisons. Pretending that's an "unfunded mandate" is self-interested foolishness. TAC should stop lying about that situation and focus on the school-finance issue where they're actually on solid ground.

Mark, you wrote: "As a taxpayer I am all for seeing that each individual gets a fair shake in court." But I don't think that's true. After all, you were earlier suggesting that defendants would be just as well off unrepresented.

ReplyDeleteRegardless, nobody said bad lawyers are a good thing, nor that they should get off the hook for bad lawyering.

But in Austin, for example, on misdemeanors they're paid $175. They walk into the courtroom, receive a file from the clerk, turn around and meet their client for the first time, and plead them out sometime minutes later. If lawyers demanded time to investigate the case or otherwise delay proceedings, they won't get more appointments because keeping the cases moving is the court's main priority. If they try to bill for more time, they will be denied. So the structural, institutional situation in which the lawyers operate DEMANDS ineffective assistance and punishes anything but. That's how things work in the real world. Should lawyers for the indigent do better? Yes. Is it possible for them to do better given the institutional, structural pressures on attorneys providing indigent defense? In many cases, almost certainly not. The ones doing the work could quit, but NOBODY could do the job effectively under those circumstances. It's a practical impossibility.

You seem to want to imply that I don't mind bad lawyering because I wrote a post on how indigent defense is financed. But there are more than 9,000 other posts on this blog and quite a few of them criticize crappy lawyering. I'm not sure why you think being critical of misrepresentations by TAC makes me an apologist for the defense bar. It doesn't. More than one thing can be true at the same time.

Pass legislation enforcing constitutional right to counsel and due process for all lower level crimes, specifically for probation/jail-able misdemeanor offences.

ReplyDeleteOR

Pass legislation decriminalizing order-maintenance and lower level possession misdemeanors.

Choice A or Choice B?

I want to point out a misinterpretation everyone seems to be making... and, as a Board Certified Criminal Defense attorney who practices nothing but criminal law for several decades now, I believe I can speak with some authority on this matter.

ReplyDeleteThe implication above is that a court-appointed lawyer does sub-par work on court-appointed cases, implying that it’s an intentional act. Wrong! That is almost 100% NOT the case. The court-appointed lawyer, unfortunately, is a sub-par lawyer. Generally, they are young, new attorneys with no experience. Once an attorney becomes good at their job, they stop taking court-appointed cases due to the fact that court appointments pay so poorly. A good defense attorney can make more money on one retained case than ten court-appointed cases. As for older attorneys who choose to remain on the court-appointed lists, they do so because they cannot “make it” only taking retained cases. Why? They aren’t any good!

Sadly, I see it all the time—court-appointed attorneys are not choosing to do a worse job... they are simply worse attorneys.