This month:

- Texas Legislature legalizes hemp and in the process may have accidentally made it impossible to prosecute workaday pot cases. Is this really a problem?

- San Antonio Judge ignores due process on probation revocations. How common is this?

- Texas Legislature created 50 new crimes in 2019

- Alfred Brown denied innocence compensation

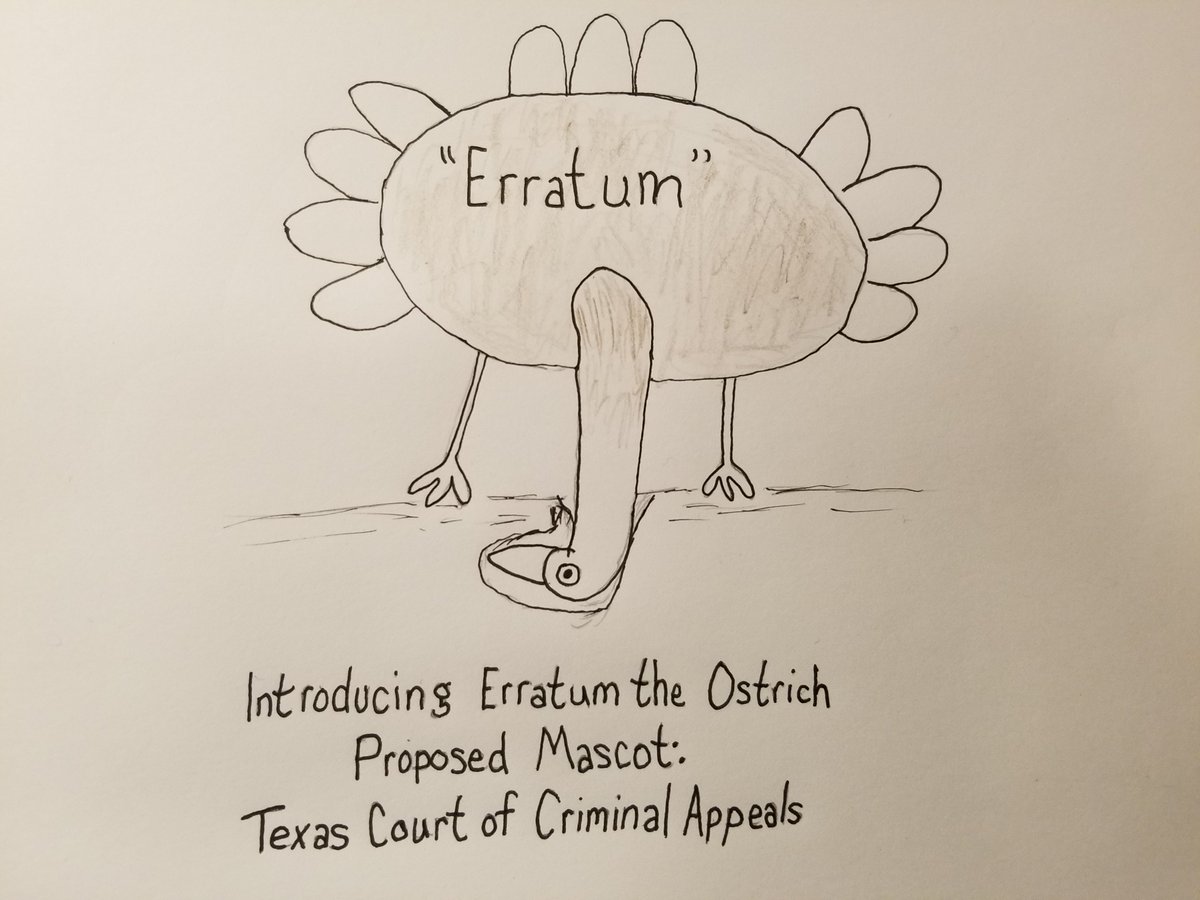

- The Canadian Supreme Court has a fuzzy mascot owl named "Amicus." What should be the mascot for the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals? My suggestion:

Transcript: July 2019 episode of the Reasonably Suspicious podcast co-hosted by Scott Henson and Amanda Marzullo

Amanda Marzullo: Hi, this is Amanda Marzullo, and this is the Reasonably Suspicious Podcast. Scott, the Texas Legislature is requiring prosecutors to prove somebody can get high from marijuana before they can prosecute the person for possessing it. What does this mean for Texans?

Scott Henson: I think it means it's always 4:20 somewhere and now it's always 4:20 in Texas, so smoke 'em if you've got 'em, people.

Amanda Marzullo: Yeah. I don't think that's what it means, Scott.

Scott Henson: Okay. Well, we're going to talk more about what it means later, I suppose, but hello boys and girls and welcome to the June 2019 edition of Just Liberty's Reasonably Suspicious Podcast, covering Texas criminal justice politics and policy. I'm here today with our good friend, Amanda Marzullo, who's Executive Director of the Texas Defender Service. How are you doing today, Mandy?

Amanda Marzullo: Never been better, Scott.

Scott Henson: All right, improving every month.

Amanda Marzullo: Yes.

Scott Henson: You say that every month, so-

Amanda Marzullo: Yeah, it's just-

Scott Henson: A constant upward curve.

Amanda Marzullo: That's me.

Scott Henson: Excellent. This month I speak to Marc Levin from the Texas Public Policy Foundation about parole reform. Just Liberty's Chris Harris stops by to discuss criminal justice's responses to homelessness and the Texas Legislature may have almost, accidentally, sort of legalized pot.

Amanda Marzullo: Or not at all.

Scott Henson: Or not at all or something to that effect. We're going to dig into it. Mandy, what are you looking forward to on the podcast today?

Amanda Marzullo: You know, misbehaving judges, which is later on down in the list.

Scott Henson: Obviously, always a fun topic.

Amanda Marzullo: Yes, exactly. Black robe disease, it affects lots of people.

Scott Henson: First up and our top story, following the lead of the Trump Administration, the Texas legislature legalized industrial hemp this session. Hemp is the same plant as marijuana, but it's now legal if the THC content is below .3 percent. The problem is no crime lab in Texas has the equipment necessary to calculate the THC percentage, so prosecutors have dropped dozens of marijuana cases around the state, claiming they can no longer prove the charges in court. Mandy, what do you think of this snafu?

Amanda Marzullo: That is a surprising issue of implementation more than really what the law is. I think most people would have expected that for someone to be prosecuted in the state of Texas for possessing a substance that it would be something that you can get high from.

Scott Henson: Right. The idea that you can have a marijuana plant that you can't get high from, but it still going to get the same criminal penalties would make no sense to anybody.

Amanda Marzullo: Yeah.

Scott Henson: It's the getting you high that is supposedly the problem.

Amanda Marzullo: Yeah, exactly. I think, as outraged or frustrated as a lot of prosecutors are in what the law is requiring them to do really just makes sense.

Scott Henson: Right. The idea that you're going to prosecute someone, you're right, you couldn't even get high from it in the first place, is problematic. That's a fix to a problem in one respect. The other thing is, the prosecutors and the cops and the police unions have just been weeping and gnashing teeth and crying about this all over and there's story after story. The reality is, there's still a lot of ways around this for them. There're still ways for them to enforce all this. First, the problems with the crime lab equipment only really applies to things like edibles or CDB oil or things like that. They can't-

Amanda Marzullo: Yeah, so body lotions, products that have hemp in them.

Scott Henson: That's right. They can test the plants and anyway, smokable plant materials excluded from the hemp statute, so that's not a problem to begin with. Also, even if someone claims, "Oh, this is industrial hemp," if they don't have the paperwork with them to show that it's industrial hemp, they've still committed a class C misdemeanor. Well, the governor wanted to change pot possession to a class C misdemeanor anyway, so no one thinks that it should be prosecuted any more than that really except I guess Dan Patrick, the Lieutenant Governor, and so-

Amanda Marzullo: I mean, a few people that work for him.

Scott Henson: That's right. At the end of the day, I think that there's still lots of way to enforce this. It does sound like there may be more of an issue for the consumable products, but even there, that's a tiny, tiny portion of the market. We're not talking about anything that's inhibiting a common law enforcement purpose.

Amanda Marzullo: Yeah, so when some prosecutors have announced that they're dropping massive numbers of cases, I think that makes me worry that they're actually prosecuting a lot of cases where someone is not possessing material that someone could get high off of.

Scott Henson: Right. I really want to see a breakdown of some of this now, some of the numbers that have come out of exactly how much resources are being expended on all of this is remarkable. In Houston, supposedly these marijuana cases are taking up 18% of the crime lab's capacity. That's kind of astonishing. I think we're wasting a lot of resources enforcing something that the public thinks should be legal straight up and-

Amanda Marzullo: Yeah, it's-

Scott Henson: ... I don't know. It's a bizarre situation. It's really funny. It's kind of like eliminating the plumbing board and making us all master plumbers on the spur of the moment. This thing where the legislature just writes laws they haven't considered well and they have weird, unintended consequences is really one of the great joys of our every two-year, post-session experience.

Amanda Marzullo: Yeah. I mean, I will say that this session seems to have more issues with this than I remember in past sessions. Maybe I'm forgetting [inaudible 00:06:02], but I do think that some of this may have been, it may have really resulted from a dysfunctional senate.

Scott Henson: Well, I'm enjoying it whatever caused it.

Amanda Marzullo: A misdemeanor court judge in San Antonio, named Wayne Christian, had a probation revocation in a DWI case overturned by the Fourth Court of Appeals because he routinely excludes prosecutors from the probation revocation process, negotiating himself on behalf of the state and refusing to hold formal hearings even when defendants request them. Scott, what do you think of this judge bypassing the probation revocation hearing process to make decision by himself?

Scott Henson: This was a fascinating, fascinating story, both the article in the San Antonio Express News and the Fourth Court of Appeals opinion and the briefs behind it. This was a situation where the prosecutors agreed with the defense on what was occurring. All of these allegations about not holding a hearing, not allowing evidence to be presented, those were all things that the state, Joe Gonzalez, the new DA in San Antonio agreed with the defense on and it really showed this judge's action in a light that we rarely get to see. It now turns out, and I think we're going to see more and more come out, but we've been hearing through the rumor mill, through other sources, that this is not a practice that's just in Judge Christian's court. This is something that may well occur in other counties and I'm hoping we can have more to say about that down the line because it really is quite remarkable.

By the way, not only did the judge not hold a hearing and simply decide by fiat, when the habeas corpus writ was filed for bond reduction and it went to the district judge, the district judge actually lowered the bond amount and was going to let her out. Judge Christian went and changed the date of an appointment that she was supposed to have. She was not notified and when she failed to appear at this appointment that he had changed the date of and moved it up five days, he immediately revoked her again. There really did seem to be, I don't know, some sort of animus or that almost seems personal. The more I think about it, though, I don't think it's personal against the defendant, I think it's personal probably against the lawyer. I don't want you to be challenging me. If you do, I'm going to punish you.

Amanda Marzullo: Who knows, but at the end of the day, this is just unethical behavior on behalf of a judge who's not behaving as a judge. The duty of a judge is to be an impartial fact finder and that is not what's happening.

Scott Henson: He literally refused to allow facts to come in.

Amanda Marzullo: Exactly, so he's eschewing that responsibility in every way and really, at the end of the day, kind of eroding our judicial system.

Scott Henson: The court said there was less than a scintilla of evidence supporting the revocation because he had allowed no evidence to come in-

Amanda Marzullo: To come in.

Scott Henson: ... whatsoever.

Amanda Marzullo: Yeah, he didn't allow the prosecution to submit evidence and he didn't allow the defense to submit evidence. It was just, I'm going to revoke probation on this person.

Scott Henson: He didn't allow the prosecution to speak. He behaved on behalf of the state and did the negotiation himself and when the defense asked for a hearing, he told them, "It's too late for that."

Amanda Marzullo: Because I've made up my mind based on my own facts.

Scott Henson: Right.

Amanda Marzullo: This is unethical behavior. I think it violates the canons of judicial conduct. It's disturbing and the allegations that it's happening on a regular basis in front of his court is even more disturbing.

Scott Henson: Right. I think that there's a lot more to come out of this story. I want to see what the State Commission on Judicial Conduct does with it because it seems to me he's clearly violating his duties as a judge. I want to see if the State Bar does anything with this because honestly, what are you doing with an attorney's license if you're just going to straight up ignore the law and do this sort of thing on your own? I want to find out how often this happens elsewhere because, again, when this story came out, one of the things that happened was defense attorneys around the state said, "You know, that happens in my jurisdiction, too," and we're starting to hear those stories. I think this really was more like... this story was more like a starting gun than the end of the story. It may have been the end of the story for that DWI defendant, but it was the starting gun for a bigger story on these motions to revoke.

Amanda Marzullo: Yeah. At the end of the day, it's going down to our judicial culture. How is it that someone can behave like this and that it isn't just a huge scandal that has really captivated a courthouse?

Scott Henson: The final thing I should mention on this that I find just amazing, all of the pictures of Judge Christian in this story are of him. He happens to operate the Veterans' Court in San Antonio and he runs the Veterans' Court wearing a camouflage robe. He actually has a robe that he clearly had custom made in military camouflage to wear on the bench and he wears this for photo ops and to perform judicial duties in the Veterans' Court. When you first see it, I almost thought that it was a joke or somebody had put in... you know, somebody had photoshopped it. Nope, that's him. That's the guy.

Amanda Marzullo: Yeah. I don't know what to make of that.

Scott Henson: This is a quirky fellow I guess we can say to begin with who's really sort of making his judicial post his own, shall I say?

Amanda Marzullo: Yeah, he's definitely.

Scott Henson: He might have taken that a little bit too far.

Amanda Marzullo: Yeah. Absolutely. Next, Marc Levin of the Texas Public Policy Foundation and the National Right on Crime Coalition recently published a pair of white papers suggesting 10 recommendations, each for reforming probation and parole. Scott sat down with Marc to discuss them. Let's hear what he had to say.

Scott Henson: All right. I'm here today with Marc Levin from the Texas Public Policy Foundation. Marc, thanks for talking with me today.

Marc Levin: My pleasure.

Scott Henson: I was excited about your two new reports and I know that's something not everyone hears very often in this world, but I'm very excited about these two reports on community supervision, probation, and especially parole that you all came out with right at the end of session. I really was most excited because this is a big expansion of you all's footprint. You all sort of dabbled in the probation reform realm for many years and made your name in that area, but then with looking at parole and now you have another new report on SWAT raids and police issues, you all are really expanding your criminal justice footprint a lot and I'm really excited to see it and happy. I wanted to talk to you about the details, but also just wanted to say thank you and I'm really glad to see that.

Marc Levin: Well, thank you. Everyone over here is a major consumer of Grits for Breakfast, so we appreciate all of your insights.

Scott Henson: Tell me about and let's talk about your parole report first. They both are really about various forms of community corrections, so they all sort of have issues that intermingle, but I really, really liked your recommendation you had on making parole release decisions based on objective factors that focus on forward looking risk. As you know, I think it's a majority of our inmates are eligible for parole at the moment and many of them are set off and don't get parole simply because of the nature of the crime. You delved into that here. Talk to us about that. Talk to us about the problem and what are some of the solutions you see that we could get around that and start paroling more people who would not be a public safety risk if they were released.

Marc Levin: Yeah. No, that's a great question. We've got these 10 Tips for Policymakers papers that folks can find on TexasPolicy.com, RightOnCrime.com and you've linked to them as well. We provide, as the paper's title would suggest, 10 tips, and each of them for policymakers, but also frankly the public on how we can improve probation and parole. The bottom line is these systems, obviously, are designed as alternatives to incarceration, but they can also be trip wires to incarceration. Half the people nationally that go into prisons are revocations for probation and parole. That's kind of the idea just from a free market conservative standpoint, we want to look at any government system, whether it's welfare, healthcare, and say we don't just want a bigger system, we want to actually get better outcomes. We're applying that same lens of accountability and scrutiny to these systems, while recognizing they do important work and we certainly want to continue to emphasize that there's a need for probation and parole, but we need to do them in a more effective manner.

Getting to your point, we took a look at what Michigan did in 2018, which was to essentially adopt what they refer to as an objective parole law and it was signed by then Governor Snyder. The idea is to focus on the future as we're looking at candidates for parole and they can't change what happened in the past, the nature of the offense. I think that you can argue certainly that legislators, when they decided these offenses were going to be, number one, eligible for parole period, and number two, they would be eligible after a certain amount of time served, they took into account, they knew that it was a serious offense and, of course, that's also true when they were prosecuted. The prosecutor knew that, and in some places, you can tell the jury even when someone would be eligible for parole, the judge before they're sentenced. That makes the argument that that's already been baked into the cake and now we ought to focus on is this person prepared to be safely released provided the right level of supervision and treatment on parole?

We took a look at all of the factors that Michigan set forth in their law, which all make very good sense. They look not just at, of course, the risk that they might re-offend, but the risk of a serious offense. I mean, after all, if somebody's on parole and has a joint, that's not necessarily... that doesn't mean we made a mistake in releasing them. If they kill someone, then obviously that's a different question. I think, as you know, one of the most common reasons for denying parole in Texas is the nature of the offense, so we're not quite there yet in Texas. I think obviously the parole rate's gone up here. I remember back when I started probably in the mid-2000s, we were looking at a 25% parole rate. Now we're closer to 35%, so [crosstalk 00:17:12].

Scott Henson: We were at 15% when I started.

Marc Levin: Yeah, and we have fewer new thousands, very few new crimes by parolees than a decade ago. We've increased the number of people on parole and we have fewer new crimes, so it's been a successful trajectory in Texas, but I think we certainly could go even further. Then, finally, it's just important for people to know the length of time someone serves in prison has no correlation with recidivism reduction. Even a year in prison is more than enough to complete most rehabilitation programs. That's not the issue. Obviously, there's an incapacitation effect of prison, but a lot of these folks have already reached an age where they're beyond their crime committing years and there's increasingly accurate assessments that parole boards can use to really, with not a hundred percent by any means, but with some degree of precision, to be able to predict what somebody's risk level is upon release.

Scott Henson: That's right. Somebody said recently that people age out of crime the way they age out of skateboarding. I thought that was a pretty accurate and insightful way to look at it and similarly, once someone gets out on parole or once they're on probation, usually you can tell within a couple of years whether or not they're going to succeed on supervision. Some of these incredibly long probation sentences or just paroling someone, but then having them spend decades and decades on supervision, those outer years of supervision are not providing much public safety bang for the buck.

Now, let's turn to probation though. TPPF kind of made your bones on probation reform and you and I both have been around these blocks a long time. For whatever reason, our probation departments in Texas have just never been able to successfully knock down their rates of technical revocations. Parole did it, parole was able to bring them down dramatically, but still about half of the people who were revoked from prison or to prison from probation in Texas, have nothing but technical violations. They haven't necessarily committed a new crime and I know, "Oh, well you don't know how serious these technical violations are," is always the response. Some of those people might have failed a drug test or they might have not shown up for meetings. All that's certainly true, but you mentioned half of new receives nationally, new prison admissions are from revocations, and in Texas I think it's 45%-47%, somewhere in there. What can be done to finally get these Texas Probation Departments and the judges who oversee them to reduce technical revocations? It's been so long. We've been fighting about this for 15 years.

Marc Levin: Yeah. Yeah. Well, you're absolutely right. There's about 24,000 probation revocations every year in Texas about half, 12,000, are technical. Those numbers have been persistently high. Now, beneath the surface, there are a number of departments that have made major reductions. I mean, Harris County's a good example, but other departments that have not implemented things like graduated sanctions and incentives, those departments kept increasing their revocations over the last decade, so statewide, we've budged maybe just a couple percent.

Now, we have perhaps, obviously, a larger population in Texas than obviously our general population, but just in raw numbers, we haven't really moved the needle statewide on probation revocations. I think your listeners mostly know we have over 120 probation departments in Texas, so just having some... which we do. We have some excellent probation chiefs who have made tremendous change in their departments in terms of reducing unnecessary revocations. Then you have just many others that have not, so that's the danger we have, whereas, obviously, we have a statewide parole system that can turn on a dime.

There's a number of things we need to do. I think it starts with making sure the conditions of probation are tailored to the individual based on a risk needs assessment because if you... Chairman Whitmire's pointed out he probably couldn't succeed on probation because there are 60 plus conditions. We tell people, even who have never been an alcoholic, alcohol nothing to do with their offense, that they can't have a glass of wine with dinner, and who's going to enforce that? I mean, we have 120 people per probation officer, so it's just like disciplining a child. You want to choose, you know, prioritize the things that are most important and actually enforce those.

Scott Henson: You don't have a lot of unenforced rules. That's right.

Marc Levin: Yeah. Enforce them not with a sledgehammer, but with a scalpel. I always make the analogy to a child that touches the stove. You don't wait until he does it five times before he touches the hot stove and then you say, "You're grounded in your room for the rest of the year," but that's what we do in probation. That's the whole notion of graduated sanctions to say, okay, well you missed this meeting, so now we're going to increase your reporting or something like that, you're going to have a curfew. There's all sort of things we can do short of revoking people to actually accomplish a purpose was to get them to comply with their probation condition. If you do incarcerate them, a weekend in jail is just as effective because all the research shows it's not the duration, but it's the swiftness and certainty of the sanction.

On the flip side, actually positive incentives are even more effective than sanctions. Literally, telling people at the beginning of probation, you're going to decide how long your probation is. You can earn your way off of this by being exemplary. You can be out of here in a year or two years.

Scott Henson: Right.

Marc Levin: That's proven to be very effective and a lot of states have capped revocations, too. Louisiana even at 90 days and they had reduced recidivism, they saved taxpayers tens of millions of dollars. North Carolina similarly did the same thing.

Scott Henson: Nice.

Marc Levin: For people that are revoked for technical violations, why have it be that, okay, you have five or 10 years left on your sentence, you have to go back for all of that and instead say, "Well, now it's going to be 120 days. It's going to be 90 days." I think that obviously the savings would be enormous and we could reinvest those into proven supervision strategies that actually reduce recidivism because one of the interesting things underneath all of this is there's very little evidence, there's actually no evidence, that many types of technical violations are correlated with a new offense. Just because somebody missed a meeting doesn't mean they're going to commit a violent offense.

Now, there's obviously exceptions, like if you've got someone who committed a violent or sex offense and they're violating a no-contact order with the victim, now that's different. I would say, "Okay, let's perhaps revoke that person for the rest of their sentence," but I think by and large we can actually do away with most technical revocations.

Scott Henson: All right. Last but not least, I really wanted to get you to flesh out, because I thought it was an interesting suggestion and an interesting comment really, I guess, more than a suggestion, but an observation. On your parole document, the last of your 10 tips was to recognize that parole agencies are not always the best provider of every intervention. God forbid that the criminal justice system can't be all things to all people. Consider a role for non-profits with strong community ties. You mentioned the Colorado legislation, which I've learned a little more about recently and how really integrated their reentry programming and parole programming has become with some of these community organizations and community initiatives.

That really is different from what we've done, which when we did our big probation parole reform to limit revocations, a lot of that went to new, private prisons for some of these short-term, revoke you for three months instead of the full-term type things at the intermediate sanction facilities, but we really didn't use this community organization's approach. What would that look like? It's so fascinating to hear Texas Public Policy Foundation endorsing this after having heard basically some liberals out of Colorado endorsing the same thing, but when I read it, I see exactly why it's a bipartisan approach. Right? I mean, it checks a lot of boxes, so talk to me about this approach.

Marc Levin: Yeah, well, I mean, from a free market standpoint, the ideas is the government isn't best suited to deliver every service and I think it's particularly true with some of the interpersonal things that really, it's easy to measure how many times someone met with their probation or parole officer, but the quality of interactions is very difficult to assess and I think there's also a need for mentoring. Not everything... If you were on probation or parole, you want to tell your probation or parole officer, "I'm doing great. I'm not even thinking of anything bad. I'm not close to slipping back." You can actually tell a mentor or a peer mentor something, "Well, maybe I am having some issues and you can help me with those."

One of the examples, in the addition to Colorado I talk about, is the Arches Program in New York City, which is a mentoring, peer mentoring for 18 to 24 year old's on supervision. They've got mentors who may have went to prison 20 years ago themselves and now they've established a law-abiding lifestyle, but they have credibility as messengers to these young adults. They've had a two thirds reduction in recidivism with that program and then, Colorado was a similar concept, but a little bit different. This is the WAGEES program, Work and Gain Education and Employment Skills. Essentially, they carved out some money from the Department of Corrections Budget to a general contractor, which enabled that... the [inaudible 00:26:37] general contractor enabled them to have very small contracts, subcontracts, to providers, some of which were run by people who were formally incarcerated, but for example, there's a kind of a one-stop center in Denver and they do job training, a whole host of services, and they've had a 2.5% return to prison rate so far. These folks are still on parole, but they're getting these alternative services or these additional services from a non-profit that's really community-based, that has a staff who can identify with these individuals on supervision.

One of the things actually I'd like to mention is in Texas, we kind of took a similar approach to some degree last session, now this session, with regard to state jail reentry because as most folks know, state jails, almost everyone is discharged without supervision. They're not eligible for parole, they can earn up to 20% in earned time from a 2011 law that we worked on. In 2017, we worked with Tan Parker and Goodwill and a number of other allies, Texas Criminal Justice Coalition, on this program, this bill that Representative Parker passed in 2017 to say you could get out early from state jail on a pilot program, a little more than 300 folks, and you would be able to do your remaining time essentially in a work-release program through Goodwill or another non-profit.

It wasn't implemented until this session because this session legislature actually funded it in the budget. We're going to get a... pretty soon, get to see that starting up and what obviously we hope to see is lower recidivism, but also positive outcomes, higher employment rate for the 300 plus participants in this program. I think that it all goes back to this idea that basically it is called community correction, so we need to put the community back into it and when it comes to public safety, it's not just the government that is responsible for that. That we can engage non-profits, engage volunteer mentors. I mean, obviously, programs that we know like Prison Fellowship and Prison Entrepreneurship Program, Bridges to Life, there's a lot of good examples of that here in Texas.

Scott Henson: Sure. Tons of faith-based stuff.

Marc Levin: Yeah, yeah, so the government isn't always the best position to deliver some of those things and I think that having people on probation or parole being able to have relationships with folks that they're not in a... you know, they're not reporting to, but they're having a more peer to peer or professional interaction, I think that's really valuable. One of the issues we also discussed in the Top 10 Tips for Policymakers on Parole paper is some of the states severely limit restrictions, place severe restrictions on people on parole on who they can interact with, so they say you can't interact with anyone with a criminal record. Well, you just precluded peer mentoring. Right?

Scott Henson: Right.

Marc Levin: Some of the best programs now we're seeing for interrupting gang violence use people that were former gang members because they're the trusted messenger. We really have to make sure that we're kind of open to a variety of different delivery models and not just saying it all has to come from a centralized government agency.

Amanda Marzullo: Next up, the City of Austin eliminated its No Sit No Lie ordinance aimed at the homeless while simultaneously authorizing a new shelter and expanded access to services. Just Liberty's Chris Harris sat down with Scott to describe local activists' Homes Not Handcuffs campaign that led to this result.

Scott Henson: Okay, Chris, tell me about the Homes Not Handcuffs campaign. Tell us a little about the genesis of how this got started and what you all were asking for, what you wanted the City of Austin to do, and I know there were compromises at the end of the process. Tell us what you finally ended up with.

Chris Harris: Sure. Thanks so much for having me. What we tried to push for with the Homes Not Handcuffs campaign was the repeal of local Austin ordinances that criminalize homelessness. Basically, behaviors associated with extreme poverty and your status as not having shelter and needing to sleep, be, live outdoors. Specifically, in Austin, there was three ordinances. There was an ordinance that prohibited camping, there was an ordinance prohibiting sitting, lying, and sleeping in the downtown area, and there was an ordinance that prohibited panhandling, both the aggressive variety and any form around certain locations, like ATMs or after 7:30 at night.

We started the campaign to repeal these ordinances and we really, the genesis of it was November 2017, the organization I was working for at the time, Grassroots Leadership, was approached by a theater troupe and this woman named Roni Chelben, who was organizing people who were currently and formerly had experienced homelessness, into doing these theater of the oppressed style shows and their next show was something called No Sit No Lie and it was about that specific ordinance told from the experience of people that had been ticketed. They wanted to know how they could have the most impact with the performance. Then, literally, within a week or two of that meeting where we kind of talked about what that could look like if we wanted to do it, the first in a series of audit reports released by the City Auditor of Austin came out and it was about these three ordinances. What they basically said was that they were costly and ineffective, they were creating a burden for people experiencing homelessness, which obviously, we already knew, and they directed the city to fix them because they also might be unconstitutional.

With that, we launched the campaign and 18 months later, we didn't get the full repeal, but we did get a drastic narrowing of all three of the ordinances that we think is going to have a big impact, positive impact, for people experiencing homelessness in the community.

Scott Henson: Okay, and the groups involved in the campaign were Grassroots, it was Texas Fair Defense, who else?

Chris Harris: That's right Gathering Ground Theatre, that theater troupe I mentioned, Mobile Loaves and Fishes was also involved, and Austin Democratic Socialists of America came in a little bit into the campaign and really added a lot as well.

Scott Henson: All right. Tell us what you ended up getting. You described what it was you were after and I know that in all these instances, what you got was sort of a compromised version. What ended up happening?

Chris Harris: What they did was that they narrowed both the camping and the No Sit No Lie to only now be prohibited if you are materially endangering yourself or someone else by the behavior. In the instance of camping, if you happen to be sleeping in a riverbank and it's raining and it's going to flood, then it doesn't really make sense to criminalize you in that moment, but the officer does have the authority to make you move, basically. That was the example that we were given for why that would be applicable in that case. Obviously, though, potentially could be some public health or safety issues related to certain things going on at a campsite, so there's some opportunity for the police to intervene.

Then, the other exception where police can still ticket is if you are making public property impassable, you are impeding the reasonable use of it, or you're making it hazardous. In the instance of either camping or sitting or lying down, this would mean if you were doing it in the middle of a sidewalk or a bike lane or a street such that people couldn't pass. If you were really taking up the entirety of some piece of public property, such that it couldn't be used otherwise for a long period of time and other people were trying to use it. Now, I think the main thing that really both of these are going to do is ensure that people can actually sit or lie down. There's a place where they can do these things that won't cause harm to anyone else, but will now allow them to actually perform the functions that we all have to perform as humans and not be subject to criminal citation.

The last thing is on the solicitation. This was the most like obviously unconstitutional. It's very much a freedom of speech issue to be able to ask for money. They would never ticket church groups panhandling, they would never ticket school groups panhandling, only people experiencing homelessness would get these tickets, so what they basically did was they took all reference to panhandling out of that ordinance. They changed it to an aggressive confrontation ordinance and it basically now is a blend of class C disorderly conduct and class C assault such that there is a... aggressive behaviors are still prohibited, if you're threatening or intimidating someone by touching or using offensive gestures or language at them, but asking for money in itself is not part of the equation in any way. People can ask for money as their first amendment right to protect.

Scott Henson: Well, the idea that giving someone a class C misdemeanor ticket that they can't afford to pay anyway was going to solve people asking for change on the sidewalk was always this bizarre concept. I mean, unconstitutional or not, and yes, I agree it almost certainly is, the just profound stupidity of the idea that that is going to solve the problem, that that's going to do anything but just end up with a bunch of homeless people in jail because they had warrants issued when they couldn't pay these tickets that you knew they couldn't pay when you gave it to them. They're begging for quarters-

Chris Harris: That's right, that's right.

Scott Henson: ... and you're giving them a ticket for 200 bucks or something.

Chris Harris: Yeah, it really highlights I think in one of the most explicit ways possible how as a society, we turn to the punitive responses, we turn to police, and courts and jails to deal with really social and economic issues, so I think that there was a lot of folks involved with our campaign that, as usual when you have compromises that we're really concerned about the level of compromise and I think I share that concern. I think to hear the police chief come in on Friday and talk about it, last Friday right after the City Council meeting, and talk about how this was going to fundamentally change how they ultimately, as police, deal with people experiencing homelessness, it really highlighted the degree of victory that this is and insist that we're not going to be using police to try to address homelessness anymore.

Scott Henson: Now it's time for our rapid-fire segment we call The Last Hurrah. Mandy, are you ready?

Amanda Marzullo: Locked and loaded, Scott. The Texas legislature created 50 new crimes this legislative session, including three new crimes that you can commit with an oyster. Scott, is there anything left to criminalize?

Scott Henson: Well, to be fair, those three new oyster crimes were all misdemeanors. They did not create any new oyster felonies. We're just stuck at 11, but we really have taken this over criminalization thing way too far. 50 new crimes, many, many more penalty increases in addition to the new crimes. This is a one-way ratchet and I really don't know what it will take to stop it.

Comptroller, Glenn Hegar, denied compensation to Alfred Brown after a Harris County court declared him actually innocent of the capital murder allegations that put him on death row for more than 10 years. Does his decision make sense?

Amanda Marzullo: No. Hegar has awarded compensation to a lot of people who have been in this same, exact position as Brown, makes no sense, it's illogical.

Scott Henson: The judge, the prosecutor, everybody agreed who was involved in the case that he was actually innocent. This is largely, I believe, because of the police union who keeps busting-

Amanda Marzullo: Busting it. It's also not Hegar's position. He's not a judicial expert. Why is he looking into the validity of a judicial order?

Scott Henson: Why indeed?

Amanda Marzullo: The Canadian Supreme Court has a fuzzy, human-sized mascot to promote the court. An owl named Amicus, which means friend of the court. Scott, what should the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals adopt as its mascot?

Scott Henson: Well, I posed that question on Twitter and our friend, Elsa Alcala had suggested it should be an ostrich, which I thought was a fine idea, so I had suggested the name Erratum, the ostrich. Erratum being, of course, an error that you have to correct in your opinion after its already been published.

Amanda Marzullo: With your head in the sand.

Scott Henson: That's right, so an ostrich with its head in the sand named Erratum I think is my current suggestion, but someone also suggested a piece of pocket lint with googly eyes and I'm open to that one as well. All right. We're out of time. We'll try and do better the next time. Until then, this is Scott Henson with Just Liberty.

Amanda Marzullo: I'm Amanda Marzullo with the Texas Defender Service. Thanks for listening.

Scott Henson: You can subscribe to the Reasonably Suspicious Podcast on iTunes, Google Play or SoundCloud or listen to it on my blog, Grits for Breakfast. We'll be back next month with more and hopefully better news. Until then, keep fighting for criminal justice reform, it's the only way it's going to happen. Shout out to Marc Levin, thanks a lot for doing the interview. I enjoyed it.

.jpg)

3 comments:

Your ostrich looks a lot like a turkey. A freudian slip of the hand perhaps ?

More like crappy, noobie artistic skills. :)

I would like to make a recommendation. The Prosecutor that ran for Judge in Montague County and told the Tea Party that he gives 10 year probation to defendants, so he can yank them back into the system. Why not investigate this incompetent Judge?

Post a Comment