But lately your correspondent has undertaken a research project reminding me that these records have much greater value than just informing policy debates of the moment. In many cases, they're the only records available involving important historical people and events. District Attorney and police agencies are among the earliest, continuously operating government departments, and case files are a rich source of detailed, local information.

This is especially important when mainstream information sources about marginalized people are scarce. For example, in New York City, prosecutor records were used to document the early 20th century exploits of an

. Wrote one of the authors of that investigation:

These files record the lives of marginalized populations, often silenced in the historical record. Poor New Yorkers, women, immigrants, queer residents, and people of color, whose lives might have evaded contemporary published material but whose voices appear -- albeit refracted through the justice system -- in these archives.

We're finding that's true in the historical stories I'm researching centered in East Austin. Researching black history in Texas from the 1920s and '30s is a tremendous slog: only a few editions of the main black newspapers remain, and the white press largely ignored black news, sports, and culture. But many of these same people interacted all too frequently with the justice system. To the extent their voices can still be discovered at all, often it's only "refracted" through that ignominious but invaluable lens.

After 75 years, Texas state law eliminates most confidentiality restrictions and discretionary authority to withhold release on criminal records, making them technically public. But most DA's offices don't treat them that way. Here in Travis County, my wife and I recently filed an open records request for files from the early 1940s. The Travis County DAO initially replied that they intended to deny disclosure under all the "discretionary" exceptions they could identify.

We appealed the matter, pointing out that the Public Information Act doesn't afford them any of those discretionary exceptions. The DA agreed, and supposedly we'll get those records soon. But what's really needed is for prosecutors to develop written policies about record retention and release, then to migrate files to local archivists better trained to handle and preserve them.

What kind of records are we talking about? Certainly, it differs case by case. But we have lots of examples because, in 2009, then-Travis-County-District-Attorney Ronnie Earle transferred 35 boxes of records, mostly from the 1940s and 1970s, to the Travis County Archivist, which also retains old records for the constables offices, the probation department, and other county law enforcement agencies.

The transfer of these 35 boxes appears to have been a one off. The archivist said there was something in the database about concerns that the files were deteriorating wherever the DAO stored them before. Regardless, they're now all sitting on a shelf at the archivist's office on Airport Blvd.

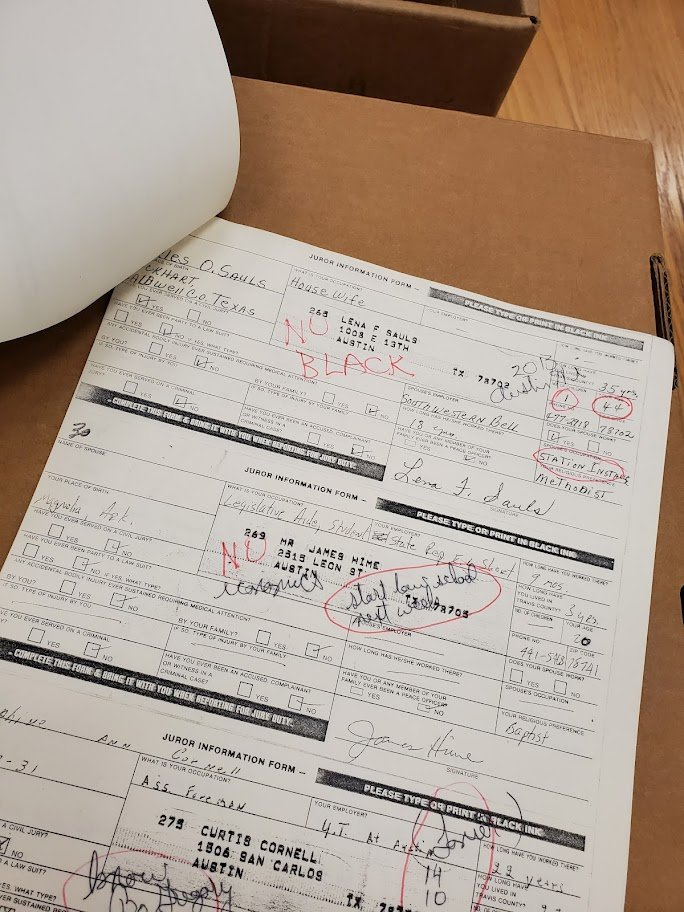

Kathy and I went to review several of these boxes to see if they contained files related to the now-long-deceased people I was researching. They did not. But Kathy noticed these documents in an unrelated case in which prosecutors adamantly struck black jurors in red pen:

I'm not a lawyer, but I'm pretty sure these aren't Batson-approved jury-selection practices. After I posted these photos on Twitter, I got an email from the Travis County DA's first assistant saying she'd referred it to their Conviction Integrity Unit! Bully for them.

This naturally spurred my curiosity. This was a case I was neither looking for nor familiar with, but I'd snapped a photo of the caption and cause number:

It turned out to involve a man named Arthur Raven and a codefendant, Audrey McDonald, and would have been an extremely high-profile case. (Long-time readers will recognize a pattern: the higher-profile the case, the more likely somebody cuts corners to secure a conviction, as with this jury-selection process.)

Raven, a white man, was the first football coach at Reagan High School when it opened in 1965 and from the beginning was highly successful, winning three 4A state championships in 1967, '68, and '70. Reagan was a predominantly black high school, built to replace the old L.C. Anderson HS, which closed in 1971. After his third state title, Austin ISD elevated Raven to become athletic director district-wide.

His son, Arthur Jr., was a Texas Department of Public Safety trooper. In 1972, he attempted to capitalize on name recognition from his father's success to run for Sheriff against 20-year incumbent T.O. Lang. Lang was a "Shivercrat," a conservative Democrat who'd spent World War II as Austin PD's liaison with the FBI hunting subversives. After the war in the late '40s, he was an APD homicide detective before running for office.

To this day, no one ever held that position longer and, after two decades, lots of people thought it was someone else's turn.

Also running against Lang in 1972 was Raymond Frank, a leftie reformer attempting to capitalize on the same momentum that ousted a wave of right-wing Texas Democrats at the Legislature following the Sharpstown banking scandal. Insiders blamed Raven, Jr., when he split the traditional law-enforcement vote, allowing Frank to push Lang into a runoff. Lang lost. And his allies were furious.

Once in office, District Attorney Robert O. Smith almost immediately turned his sights on Frank. A grand jury under his direction issued a report critical of the new Sheriff. Frank turned around and accused Smith of corruption and

manipulating the grand jury.

Arthur Raven, Sr., was accused of coercing prostitution while all this was going on, but

convicted of a lesser, misdemeanor charge while the jury acquitted his codefendant. We didn't read the whole prosecutor's file, just this portion concerning jury selection. But news accounts say Raven took the stand in his own defense, testifying most of the day as the defense's only witness. Your correspondent hasn't done enough research to form an independent opinion, but Raven certainly thought he was being railroaded.

Was Smith retaliating against the old ball coach because his son's campaign helped the DA's nemesis get into power? Grits has no first-hand knowledge. But I bet I'm not the first person to imagine so.

To be clear: I haven't read the file and just snapped a few photos and read a few news clips. I don't know who was in the right in these controversies, whether Arthur Raven, Sr., was guilty, or if his prosecution was politically motivated. But this glimpse into the historical record shows how important these old files can be to interpreting past events. Knowing prosecutors went to unethical lengths to exclude black people from Raven's jury is an important part of that story that would remain hidden if one relied only on news accounts.

In 2009, Ronnie Earle (God rest his soul) thought it was fine to make records from the 1970s public at the Travis County Archivist. That policy should be formalized. It's a waste of scarce resources at the District Attorney's office for lawyers to review every request. Better to pass that task along to library-science professionals employed precisely to perform these tasks.

I'm looking forward to receiving the records we requested, which I have no doubt will answer a long list of nagging questions surrounding the historical research Grits has been working on.

Once we get them, the next step is for the DA's office -- eventually, for every DA's office -- to develop written policies for retention and release of historical records. We hear a lot about police and prosecutors as custodians of public safety. They should also be recognized as custodians of history, and behave as such.

.jpg)