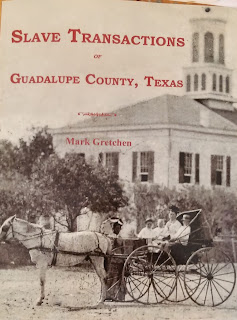

Grits' slave-patrol research homed in on Guadalupe County, in large part because records there have been preserved. I'm not the only one to take advantage of that serendipity. In Mark Gretchen's remarkable 2009 genealogical volume, "Slave Transactions of Guadalupe County, Texas," he included a comprehensive list of slavery-related criminal charges from Guadalupe County criminal court records. Almost all (20 out of 28) involved white defendants, not black ones.

To an extent, this should come as no surprise. Slave patrols were empowered to punish black people without judicial oversight. State law authorized them to give slaves up to 25 lashes for violations, and in some places like San Antonio or Indianola, the law authorized slave patrollers to give up to 39 lashes. Indeed, noted Gretchen, "by 1860, the only two sentences provided for convicted slaves in the Texas penal code were death and whipping." White folks, however, had to be taken before a judge.

Most of the slavery-related indictments against white folks in Guadalupe County were eventually dismissed or resulted in an acquittal. Even so, then, as today, you might beat the rap but you couldn't beat the ride. Those folks were still arrested by the patrol and conveyed to authorities, even if formal punishment seldom followed.

For example, Joel E. White was indicted in 1850 for purchasing a horse for $20 from a slave named Lawrence without receiving permission from his owner, Manuel Flores, who fought in the Battle of San Jacinto and was a brother-in-law of the town's namesake, Juan Seguin. The case was dismissed.

Ernst Schram was indicted for purchasing a cowhide from a slave without written consent of his owner, Samuel Millet, one of the larger slave owners in town who would later perish in the Civil War.

Otto Wupperman was indicted for purchasing a bushel of potatoes for a dollar from a "copper colored" negro named Henry who belonged to Andew Herron, a wealthy Presbyterian minister and one of the town's larger slaveholders. Herron owned 22 slaves at the time of the incident.

Gustav Thiessen and Louis Hipp were both indicted for selling spirits to slaves, with charges later dismissed.

Thomas Wilson stood trial for allegedly harboring a runaway slave named Maria, the only slave owned by a local named William A. Farris. The jury returned a Not Guilty verdict in May 1856.

A couple of cases against white folks resulted in convictions and a $50 fine: James W. Fennell was indicted in 1863 for "Placing Slaves in Charge of a Farm or Stocke Ranch," while Thomas J. Perryman that same year was indicted for "Keeping Slaves on a Farm Detached From His House." In both cases, the slaveholder failed to keep a free white man on the premises to govern them. Ironically, the law forbidding slaves from living in a detached dwelling was passed in 1858 by H.E. McCullough, the state senator from Guadalupe County.

That these are the only two cases against white people resulting in a final conviction and punishment tells us that allowing black people to live and work independently was taken especially seriously by authorities.

However, the most common charges against white folks were things like "Permitting Slave To Hire Time" and "Hiring Slaves To Slaves." The law allowed slaves to work for wages only in a limited way. Grits was unaware of this limited proletarianism afforded slaves in Texas and have never seen it discussed before. Turns out, after 1846, slaves could hire out their own time one day per week or a full week during the Christmas holidays. Beyond that, their owners could theoretically be prosecuted for letting them earn their own money.The year 1856 saw seven such cases. In the only instance resulting in a conviction, John M. Anderson was convicted and fined one cent: He appealed and the Texas Supreme Court overturned the conviction and dismissed the case. Apparently, prosecutors took this as a sign that all such cases were doomed. No more charges for "Permitting Slave To Hire Time" were recorded in Guadalupe County after that episode.

Only one case in the records involved a white man accused of abusing a slave. Clinton DeWitt was the son of Green DeWitt, empressario of the famous DeWitt Colony, and a well-known sadist. In 1847 he was indicted for "Unreasonably Abusing a Slave," though charges were eventually dismissed. Dewitt was later killed by his brother in law, shot to death while he was beating his wife with a bullwhip.

The brother-in-law, Tom Frazier, escaped but was later brought to trial for the murder in 1886. An unnamed former slave testified he was not the killer: "No, this man is not Tom Frazier. The Tom Frazier I knew is much younger and if the Tom Frazier I knew had not killed Clinton E. DeWitt, I was going to kill him." The jury acquitted Mr. Frazier.

All of the slaves indicted were for either assault or murder, including a slave named Dina indicted for throwing a rock at a white woman. If she'd been convicted, it would have resulted in a death sentence, but a jury found her "Not Guilty" in December 1859.

A slave named Jack was convicted of murder for killing his pregnant wife with an axe because she had informed on Jack to his master regarding some transgression, for which the master intended to beat him. Jack was considered a well-liked, gentle person known for making wooden toys for children in exchange for food, and his crime produced quite the local scandal. Some 1,500 people attended his hanging on the banks of the Guadalupe River and his owner was paid a portion of his $1,200 value to compensate for his lost property.

Except for these few criminal charges involving violence, the record remains silent on punishments issued to black folks, most of which were almost certainly imposed by the patrols without judicial oversight. Across the street from the courthouse in Seguin stands an old tree dubbed "The Whipping Oak" with a metal ring embedded in the wood for attaching the shackles of the person to be lashed. After the Texas Legislature ended corporal punishment for white people in 1848, only black folks would have been beaten there. We can only guess at the volume and intensity of those events: The historical record remains silent on the matter.

These records expand our understanding of Texas slave patrols by emphasizing their authority over white people as well as slaves. Maintaining racial separation and preventing black people from living independently were as much goals of the patrol as preventing runaways.

See prior, related Grits posts:- Racism and the origins of Austin policing: A history lesson for the governor

- Slave catching the dominant, early Texas law-enforcement apparatus

- Houton's early police chiefs: the thief, the Chief who wouldn't be fired (sound familiar?), and the Mysterious Disappearance of John Proudfoot

- Early Texans couldn't get enough slave patrols but didn't want to pay for them

- Republic of Texas passed law against being free and black

- Slave Patrol Research Update and Request for Research Advice

- A Texan Huck Finn, Proletarian Slaves, Dreaming of Mexico, and the Habeas Revelation: Lessons from runaway slave stories

- Can police patrol functions be separated from racist slaver legacy? Maybe not

.jpg)

9 comments:

I posted the below thought previously for which no response has been made.

“Grits - I believe your research is generally factually accurate for which I have either read (or glanced over) in prior postings. Tying the origins of LE to slave patrols is probably accurate to a degree. However, it is like an incomplete sentence if you don’t also discuss the elected officials of those periods of time which codified LE authority and criminal violations of that time.

If the elected majority party at that time (you pick when) was democrats, republicans, etc. are they the root cause? “The Wikipedia“ (I take Wikipedia with a large grain of salt) reflects of all the Texas governors: 39 were Democratic, 7 Republican, and three others of varying parties. While the governor does not make laws, he/she can veto laws and provide legislative priorities.”

Since you listed specific dates, I’ll make the correlation to the governor’s party for those dates:

1846/47 - Democratic

1848 - Democratic

1850 - Democratic

1856 - Unionists

1858 - Democratic

1859 - Democratic

1860 - independent

1863 - Democratic x2

Having the governorship dominated by one party (1840s-1860s), who played a major role in codifying LE’s authority and the statutes enacted of that period, one could reasonably conclude the Democratic Party of that period enacted and enabled the mistreatment of the black population.

@Thomas is right, the LE didn't act on their own, nor did they establish their own organizations organically. LE is established to E the Ls enacted by politicians, all of whom owe fealty to a party. Therefore, the identity of the party who championed unsavory Ls to be Eed is valid data.

Certainly it's "valid data." What's invalid is an attempt to inject that observation into a discussion about modern parties, as the political parties have since reversed sides on civil rights. You both know full well Rs and Ds flipped positions on civil rights in the '60s. Pretending 21st century Rs are in any way akin to, e.g., post-civil war Radical Republicans who championed black liberation, is an historical misrepresentation. All the old Dixiecrats became Republicans and that's inarguably their modern political home.

BTW, I was attempting to focus on the LE history and not engage in partisan bickering. To me, LE issues are nonpartisan, neither R nor D. But if you're going to try to turn it into a partisan debate, let's be honest about the modern context.

Grits - I understand the parties flipped and thus my statement “Democratic Party of that period enacted and enabled...”. I’d content omitting the politics and primary political party of that time to solely demonize LE of the 1840s-1860s+ is short sided at a minimum. Call them all demons.

I didn't omit it to demonize anyone. I omitted it because it's irrelevant to the topic at hand. Why do you bring it up? If they were Whigs would it make any difference?

If they were Whigs, I too would have listed them for accuracy. If the Whigs were the political party that codified law enforcement and statutes of “that period” which treated blacks ill, it is relevant. Regardless of who (party wise), it is relevant as someone sought the formation of LE and asked LE to do a job, slave patrols as your research shows. The political parties of that period (1840s-1860s+) are not the same as today. Likewise, LE of that period are not the same as LE of today. I realize your intent is to show the origin of LE as it relates to slavery and I agree with your general findings. Interjecting “how”, “why” and for “whom” created these slave patrols is important too.

What have I written that's "inaccurate"? Seriously. Quote the inaccuracy or say what I wrote where omitting the word "Democrat" creates a misimpression. It doesn't. It's just irrelevant to the topic. You're the only one who cares and it's because you want to make this about present-day partisanship, implying Democrats of today share 1858 values on race.

If you understand that the parties "flipped" on civil rights then you understand that no understanding is gained from emphasizing party structures from the past (without much more unnecessary elaboration that can be avoided by focusing on the actual point). Political positions of the antebellum Democratic Party are not germane to the present day party in a meaningful way, in large part because black people are allowed in now and its positions have changed! By contrast, the *policing structures* established in this period are still with us in their original forms. That's the history I'm interested in. The partisan stuff is your thing.

I said “I agree with your general findings” and “factually accurate”. Both compliments. We can agree to disagree about how, why and whom created LE in Texas is relevant or not to the history of actions of LE.

“Policing structures established in this period are still with us in their original forms”, yes. Each LE agency is created by a governing body, possess a chain-of-command, and provides some form of function (enforcement, regulatory role, public safety, etc.). I agree with you again.

Post a Comment