Grits readers have seen me complain about sensationalist, de-contextualized media coverage of crime and punishment nearly since this humble blog's inception. Turns out, if your correspondent had been transported in a time machine to the early 1920s, the problem would be even worse and Grits may well have gone clean out of my mind.

Recently, I ran across what appears to be the earliest quantitative analysis of media crime coverage in America in a massive, 700+-page document titled, "Criminal Justice in Cleveland: Reports of the Cleveland Foundation Survey of the Administration of Justice in Cleveland Ohio." On p. 544 of this behemoth, we find this remarkable assessment of a media driven crime panic over the course of one month in Cleveland and the predictable, and current-day-relevant policy results from this brand of journalistic malpractice.

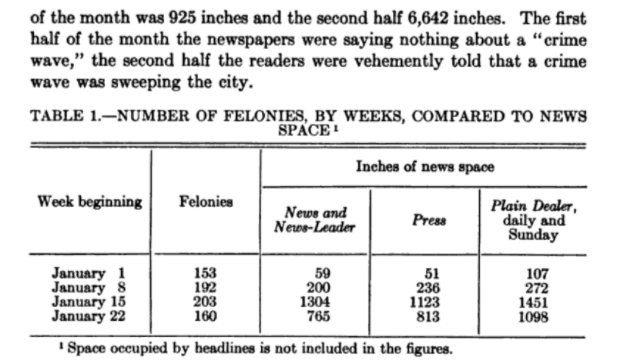

The Cleveland Foundation summarized its criticisms of local media coverage thusly:

Further:

The same sort of misguided attacks were made on parole decisions, focusing on high-profile recidivists while ignoring more numerous, less-attention-grabbing success stories.

The Cleveland Foundation wrote this near the height of a massive, media-driven crime-wave panic. Google has a search function to see how often a word or phrase was used in books they've scanned that were published that year. Here's the graph for the phrase "crime wave."

I've read more than a few historians and critics over the years trace the American media's crime obsession to the cases of Bonnie and Clyde and John Dillinger in the 1930s, when such outlaws became well-known anti-heroes in the eyes of huge swaths of the public. But this graph and the Cleveland survey tell us that compulsion was in full flower - and perhaps even more intense - more than a decade earlier.

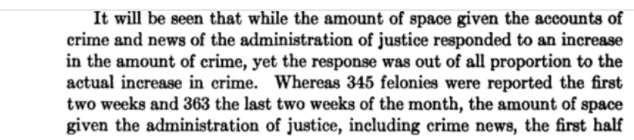

Perhaps most telling was their depiction of an episode in 1919 Cleveland which could have been taken straight from 2019 Houston:

During January and February, 1919, there occurred what was known as the 'bail bond expose.' ... It became known that a number of persons suspected or actually arrested and charged with crimes had been previously under arrest and released on bail. Special newspaper attention was given to the fact that bail was fixed by judges on the recommendation of the prosecutor, and in view of this power of fixing bail by recommendation the prosecutor was urged to demand higher bail.

The over-the-top language was totally out of proportion with all data and designed to mislead and rile up the public. For example: "The toll of pillage and murder increases. Gangsters scoff at law and courts. And peaceful citizens shudder."

This is reminiscent of a litany of overhyped commentary in Houston - most of it in TV news stories quoting Andy Kahan at CrimeStoppers or Houston police Chief Art Acevedo - criticizing judges for lenient bail practices. So this is at least a century-old trope: You could use the same time machine to transport those two back to the 1920s (indeed, I wish you would) and their quotes would blend right in with the rest of the media landscape. In fact, the results of their advocacy in Houston have been similar to the unintended (but predictable) consequences in Cleveland: Jails full of low-level offenders who needn't be there. From the report:

Many of those locked up were liquor law violators who couldn't pay fines; some who couldn't pay were sent to "the workhouse." Even so, the Cleveland Foundation lamented that "the work of individual judges receives special but wholly erroneous interest" in the press, and that demagoguery against judges became so intense that one judge received personal death threats. Even more concerning to judges, however, were the day-to-day practical problems it created:

Houston judges are in the same boat. The jail is currently overcrowded as a result of some combination of regressive media influence, COVID-driven court backlogs, and the governor's executive order limiting bail. The COVID delays are exogenous to this question, but media pressure on judges and the governor's executive order are directly analogous to the judges' and prosecutors' actions in response to media coverage in Cleveland. Here's the

lede to a recent Houston Chronicle story about overcrowding at the Harris County Jail:

Preston Chaney died of COVID-19 after more than three months at the Harris County Jail on allegations he stole lawn equipment and frozen meat. Two days later, Chaney’s court-appointed lawyer, who’d logged just two hours on his case, billed for additional work.

Chaney had a hold and was rejected for personal bail under Gov. Greg Abbott’s pandemic order banning the release of anyone with violent charges or prior arrests. Had the 64-year-old been able to scrape together $100, he could have waited for trial away from the packed downtown lockup.

This was an avoidable death. Tuff on crime demagoguery has consequences. Local media, particularly in TV news, deserve a share of the blame for it.

.jpg)

2 comments:

If you used that time machine to go back to the 1920s, you’d likely complain almost exclusively about the Democrats in office that created the majority of the laws of that period.

If you think this blog shies away from criticizing Democrats you haven't been reading too long.

Post a Comment