One of the items on my

research checklist regarding slave patrols and early Texas policing was to examine newspaper items on runaway slaves from Guadalupe County (and perhaps others going forward) in order to identify anecdotes that a) humanize the history I'm reading in old commissioners court records and b) clarify the role and functions of slave patrols in Texas vis a vis the more traditional law enforcement apparatus, like Sheriffs or City Marshals (Texas' precursors to modern police departments). Luckily, some of this legwork has been done by Kyle Ainsworth and his students at the Runaway Slave Project at Stephen F. Austin University in Nacogdoches. Let's go through the notices they've compiled from Guadalupe County both to record the stories and see if they provide further research avenues. You're basically just seeing my raw notes here, but it's as good a place to put them as any.

A Texan Huck FinnMy favorite of these stories I think of as Texas' Huck Finn. According to The Texan Mercury, a paper out of Seguin, in 1853 a young German boy stole a horse and apparently helped a runaway slave to escape. They were captured, likely by the slave patrol, and brought to the Sheriff to be held. But they broke free and fled again, possibly together headed to Mexico. The short article was published on 10/8/1853 and used the incident to editorialize in favor of the county constructing a proper jail less prone to escapes. Research followups: Check district court for "German boy's" horse thieving case. Also: Find out when the first Guadalupe County Jail was constructed and look at public debate surrounding it.

Dreams of Mexico: The Destination

According to the 9/9/1854 Texas State Gazette, one runaway slave from Guadalupe County drowned and three more were captured trying to cross the Rio Grande. The Austin paper blamed the existence of Mexicans living in white people's midst: "It is daily becoming more difficult for the slaves to get into Mexico, and by a little timely exertion in clearing our country of rascally peons, we think the planter in Texas will be more secure in his slave property than most other Southern states." Research angle: Perhaps border sheriff records on captured slaves could be fruitful? Were there patrols in border counties? Was there pressure from slave holding counties to enforce south-bound border and what was local law enforcement's enthusiasm level? Idk. For that matter, I want to know more about free, black communities in Mexico. Hoping this item on the reading list will fill in some of the gaps.

Anti-Mexican sentiment among slavers

The same issue of the Texas State Gazette reported on a public meeting in which locals agreed to collectively offer $250 reward for capture of escaped slaves. Slave owners were so obsessed with the idea that their property might flee to Mexico, the group voted to recommend banning "peons," by which they mean vagrant or unemployed Mexicans, from Guadalupe County outright. Presumably they believed black people couldn't walk south without a guide, though there is evidence that Mexicans near the border helped runaway slaves survive the desert and get across the river, typically for a fee. Sometimes passage across the river was exchanged for indentured servitude with Mexican hacendados. Finally, and most ominously, the group in Guadalupe County "provide[d] for a standing committee of twenty discreet men to enforce the resolution." To me, that sounds like people planning for vigilante violence against Mexicans. Reported the Gazette:

The peons, to which this meeting refers, have no reference to the permanent Mexican citizens, many of whom are worthy men and generally esteemed, but to a vagrant class--a lazy, thievish horde of lazaroni (editors note: OMG!! most original homeless slur I've heard in months!), who in many instances are fugitives from justice in Mexico, highway robbers, horse and cattle thieves, and idle vagabonds, who prowl about our western country with but little visible occupation or pursuit. Indeed, many of the robberies and murders attributed to Indians have been the work of this class of men. A new trade has been opened up to them, in aiding the escape of slaves. They scruple at nothing, and a few dollars from a negro is sufficient to secure their services. If a summary punishment is visited upon them, it is certainly what they may well expect from our incensed countrymen; and in the absence of a prompt and efficient remedy through the laws, this abuse will be corrected by the citizens themselves as a matter of self-preservation.

Guadalupe County's resolutions inspired similar ones in Bexar County, and a statewide slaveholder convention was announced for Oct. 2, 1854 in Gonzales to discuss the matter. Runaway slaves were treated like they required quarantine: "All slaves brought back from Mexico are to be sent off to a foreign market and disposed of, and up to that time, they are to be closely guarded and not permitted to associate or converse with other negroes." Research notes: Need to find out more about this slaveholder gathering: Check newsclips, secondary sources. Also, are there records of runaways disposed of in "foreign markets"? How would one research this? Idk.

Proletarian slaves in Texas

On 7/1/1854, the Texan Mercury mocked the notion that a slave named Alfred belonging to a local "mercantile firm," was caught in public in possession of hundreds of dollars and his employer said it was his. As an aside, Alfred may have been an example of black folks working in an economic scenario I'd never considered before launching this research: Slaves who hired themselves out for pay and gave master a cut, but lived independently like a proletarian. Newspapers complained of this practice in every large Texas town (see, e.g., this Austin case study), so it was as widespread as it was scorned by white supremacist absolutists. They thought it would give other black folks ideas and foster an inappropriate sense of equality and independence among them. In 1856, the Texas Supreme Court ruled in a Guadalupe County case that slave owners could not be prosecuted for allowing their slaves to accept employment. In my estimation, this practice arose because slavery as a business model didn't work as well in the cities as on the plantations. The economic incentives to let slaves hire themselves out probably drove the decision more than some urban libertarianism. More money with less hassle and responsibility? I'm guessing some urban slaveowners said "Sign me up!"

More runaway examples

On July 11, 1859, a slave named Oben belonging to Guadalupe County slave owner James George was reported captured in Bexar County, likely by the patrol, and taken to the Sheriff to be held. Followup: Check George in GC Slave Transactions book.

On January 25, 1862, a slave named George, reportedly belonging to a slave owner who'd left town the prior year, was captured by the patrol and incarcerated in the Guadalupe County Jail.

Habeas! Of course!

As Bexar County is next on the list, I was interested to discover this habeas corpus case which may be instructive: A dark-skinned Mexican woman was captured by a slave patrol and accused of being a runaway without evidence, though witnesses supported her story. Research notes: How hadn't I considered habeas corpus cases as a source for anecdotes? I love 19th century habeas cases! Will have to consider how to identify those. Maybe a start is this database of black Texans with cases before the Texas Supreme Court in that era. Another tedious but potentially fruitful research path.

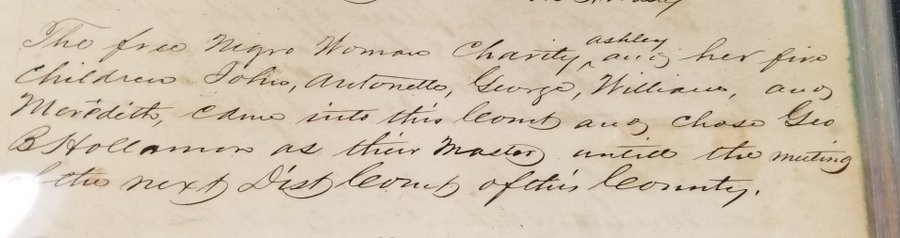

Charity Ashley: Free but for (a terrible, horrific) choice

Finally, a bit more detail on the story of Charity Ashley, the free black woman with five children who

chose to re-enter slavery and take on a new master in the late 1850s. (Texas

banned free blacks during the Republic and as a state passed coercive legislation aimed at forcing them back into slavery.) I found a

brief mention of her decision in the commissioners court minutes, which referenced a District Court hearing I still need to research. Anyway,

according to the 1850 census, Ms. Ashley was born in South Carolina and at that time was 36 years old, making her roughly 44 when she reportedly

sought out a local patroller as her new master for her and her five kids. Though it doesn't mention her or her family, the Seguin Gazette-Enterprise in 1996 ran an

historical profile of George Holloman, the slaver and patrolman who became her new master.

Ashley and her children were

listed in 1850 as living at the same dwelling as the families of John A.M. Boyd and William King, but separately under their own name, not as property. I wondered on Twitter, "What arrangement led her to be staying there? How did she make a living? How did she come to be free and why was she living in Texas w/o a husband? When the state decided to coerce free blacks back into slavery, why didn't she choose Boyd or King as masters?" If she was already in Seguin with five kids by 1850, Ms. Ashley was a relatively long-time resident by the time she chose a master, and probably one of the few free, black people in town. So many questions! I can't wait to see the district court file in her case, assuming it still exists 170+ years later.

A Forgotten Precursor to Secession

Professor Ainsworth from SFA tells me slave patrols ramped up following the little-known "Texas Troubles" in 1860. Certainly, in 1862, the Legislature expanded the patrol requirement to mandate weekly rather than monthly outings,

according to Randolph Campbell's "Empire for Slavery." But some Texas cities may also have created patrols, if sometimes short-term. Occasionally, antebellum Texas witnessed the activation of informal, pre-Klan vigilante networks. There's no way to know the overlap, if any, between those mobs/posses and patrol membership. But things could erupt quickly.

The all-but-forgotten episode referenced by Prof. Ainsworth involved white Texans misinterpreting a series of fires caused by a faulty batch of matches as evidence of Negro insurrection and arson. This was false, but up to 100 or more black folks and several white (alleged) abolitionists were lynched or otherwise murdered in the aftermath. Dubbed the "Texas Troubles," the incident with the faulty matches was a more important,

proximate cause of Southern insurrection fears when they seceded than Nat Turner's rebellion decades prior. But today they're mostly forgotten.

Slaves foraged for food during Civil War shortages

I haven't yet found Texas slave narratives that mentioned patrols. But I did see a passage that presented the

hardships facing slaves in Texas during the Civil War period.

During the Civil War time were very hard. I have known slaves to pull up tobacco stalks and smoke chip them and use okra seed for coffee; [to] build pens in the woods and catch turkeys. [They would] lay poles on top, dig a hole under the bottom of the pen, and drop corn fifty steps leading up to the pen. The turkeys would go in. After they eat they would never look down. Deer would have a regular place to jump in the filed. Slaves would set a stob and sharpening [the] upper end and sometimes catch a deer. Father did the weaving during the Civil War. I imagine seeing him dashing the sickle right and left, the women carding and spinning.

See prior, related Grits posts:

.jpg)