Tuesday, February 23, 2021

#Txlege should use savings from closed prison units to fund needed treatment services

Monday, February 22, 2021

Plano police do best 'Cartman' impersonation arresting black kid for walking home in the snow

Rodney Reese, an 18-year old black man living in Plano, was walking home from his job at the Walmart during the Snowpocalypse when police officers stopped him ostensibly for a "wellness check." Carrying a plastic bag, underdressed for the cold in a short-sleeve shirt, he told them he didn't want their help and was on his way home. But the cops wouldn't take "no" for an answer and soon told him he was under investigation and being formally detained, eventually arresting him for "pedestrian in a roadway." To their credit, the Plano PD quickly posted the dashcam video. You can watch the video here.

A couple of things stand out. First, despite the police chief saying he didn't believe race was a factor, it's virtually impossible to imagine Plano cops treating a white 18-year old boy in a similar fashion, or for that matter that any Plano resident would have called the cops in the first place if the boy were white. That's just the truth. The chief said he can't know what's in officers' hearts, but their actions revealed more than words could convey short of calling him the N-word. They weren't treating him like a citizen whose wellbeing they cared about - the ostensible purpose of a "wellness check." He was there to play a role, in their minds, and was punished for refusing to go along with the charade.

Second, there was no public-safety justification for what happened. Reese told them he was going home and was under no obligation to talk to police. (One has a "right to remain silent," after all.) He'd done nothing wrong and his incentive to keep moving and not stop in his under-dressed state was obvious; there was nothing suspicious about his behavior. He was arrested because he chose to exercise his rights.

That element reminded me of the episode in Keller, TX with Dillon Puente and his father. There, the cop got upset because Puente said he was afraid of him, citing images of police brutality on television. Rather than try to understand where the kid was coming from, the cop considered his reticence to interact suspicious and ended up arresting him for making a wide right turn. (In that case, officers also pepper sprayed and arrested Puente's father who was shooting video of the episode.)

Watching the video from Plano, the male cop escalated the situation unnecessarily. The woman initially approached Reese used a lighter touch, but should have taken "no" for an answer. The male cop, however, exhibited what can only be described as a bout of toxic masculinity, tinged with racial animus. This black boy challenged his authority by ignoring him, and that the cop couldn't abide. It was like watching the character Cartman from Southpark insisting "You will respect my authority!" Same energy, as the kids say.There likely was nothing this kid could have done to avoid this outcome. The cops weren't sent there to investigate a crime, but invoked their investigative powers the moment he failed to show maximal deference and detained him for no good reason. He was 100% right not to want to engage with them.

Mr. Reese was charged with being a pedestrian in the roadway - a Class C misdemeanor - and hauled off to jail. The maximum penalty for that offense is only a $500 fine, so the arrest punished him to a greater extent than the maximum a jury could have imposed following a guilty verdict.

On Facebook we're told, "The arresting Officer noted in the arrest report that although the subject committed the Class B misdemeanor offense of Interference with Public Duties by resisting Officers efforts to detain and handcuff him, the Officers elected to only charge him with Pedestrian in the Roadway, a Class C misdemeanor." This tells you all you need to know about the officer's mentality, framing it as though he was doing the guy a favor. What "duty" was he performing that Mr. Reese interfered with? Checking on the boy's wellbeing. But the kid already told him he was fine and on his way home. In truth, the officer was violating his duty to respect the lad's rights.

Finally, I should add that the Plano Police Chief, who himself is black, to his credit, immediately ordered charges dropped against the kid and said the arrest should never have been made. And he deserves a lot of credit for releasing bodycam video footage so quickly, that's exemplary police management behavior rarely seen in Texas' larger jurisdictions. But his comments absolving the officers of racial motivations rang hollow: It's not credible to imagine white kids in Plano get treated that way. If they were, likely arrests for Class C misdemeanors would have been forbidden a long time ago.

Thanks to data collected under the 2017 Sandra Bland Act, we now know that 64,100 people were arrested for Class C misdemeanors at Texas traffic stops in 2019, and untold more were arrested on the street for Class Cs, like Mr. Reese. Every one of those arrests was an abuse of police power just as much as this was. It has to stop.

Sunday, February 21, 2021

Radio silence re: ransomware attack on Texas courts

This reminds me we've received almost zero information about the ransomware attack on Texas courts last year, and no journalist of whom I'm aware has dug into the topic beyond notices based on agency press releases.

The breach impacted not just the Texas court system but all the agencies under the Office of Court Administration's umbrella, including the Forensic Science Commission, the State Prosecuting Attorney, the Office of Capital and Forensic Writs.

I've heard anecdotally the OCFW faced problems filing briefs in the aftermath of the breach. The Forensic Science Commission was in the middle of rolling out accreditation for forensic analysts when it happened: no word on how any of that was impacted.

Not only has there been virtually no journalism on the topic, there were no public hearings in the interim (the year between Texas' biennial legislative sessions) for legislators to learn what happened or how to prevent it from happening again. It's been near-complete radio silence.

I'd like to believe Texas officials quietly fixed the problem and it won't happen again, but after watching how the state was managed during last week's Snowpocalypse, who believes anyone in state government is either a) competent enough to actually fix problems and b) humble enough not to brag about it if they did? Grits suspects the silence instead is cover for problems we weren't told about.

MORE: Here's an academic piece by David Slayton from the Office of Court Administration giving the most detail I've seen on the Texas courts breach. ALSO: There was another major ransomware attack on CJ systems in Texarkana in December.

Thursday, February 11, 2021

Texas oyster crimes are no joke and a symptom of broader problems

Marc Levin, who recently left the Texas Public Policy Foundation to become general counsel at the new Council on Criminal Justice, first launched this meme as a way to critique overcriminalization, highlighting the fact that Texas has so many felony statutes on the books it's difficult even to count them.

Your correspondent played into the gag, wondering aloud how many crustacean-related crimes are sex offenses and counting the number of oyster-related felonies in "The Walrus and the Carpenter."

Over the years, however, Grits has come to realize Texas' "oyster crimes" aren't just a silly government foible to be mocked at conservative conferences. (TPPF for years held a panel at their biennial legislative conference highlighting "overcriminalization" and featuring this example.) Rather, they're illustrative of some of the core challenges involved in disentangling criminal law from regulating non-criminal behavior in a society organized around what Jonathan Simon has called "Governing through Crime."

Texas has so many oyster crimes on the books for two, fundamental reasons: Scorn for regulation and the environment. Harvesting native oysters is terrible for the latter and the Legislature prefers criminal law to the former.

Including misdemeanors, Texas has dozens of oyster-related crimes on the books, all because the state uses criminal law to regulate unwanted business practices that other states manage through non-criminal regulatory enforcement.

In most other coastal states, civil regulators enforce rules about oyster harvesting. In Texas, it's game wardens and prosecutors. This leads to a spotty patchwork of enforcement dependent on some random lawyer elected DA knowing and caring about the topic and/or being willing to ignore local donors who might object.

For years, the prosecutors' association scoffed at the oyster-crime depiction, insisting such cases were rarely prosecuted. An old college pal of mine who's written their law books for the last couple of decades said the same thing on Twitter when the oyster-crime meme arose this week. But if that was ever true, it's not any longer.

Hurricane Harvey disrupted the unfettered harvesting of native oysters, requiring more robust state regulation for the industry to survive. Texas A&M Professor Joe Fox noted in 2019, “Due to overfishing, excessive freshwater inflow and loss of infrastructure mainly due to hurricanes, Texas oyster harvests have been trending downward and have experienced a 43% loss in the past three to four years.”

That's what's generating the push for greater enforcement. Without it, the industry could vanish. But prosecutors aren't regulators. Their job is to prosecute crimes, not regulate aquatic industries, even if the latter task de facto falls to them under Texas' absurdist system.

Even if you took these criminal laws off the books, state intervention would be needed for this industry to exist. Otherwise, overharvesting would wipe out the native oyster population in short order. In the 4-day sweep in December, game wardens restored 48,000 pounds of illegally harvested oysters to the bay. In a similar sweep in 2018 netting twice as many cases, "Some of the violators intercepted had cargo consisting of up to 35 percent undersized oysters."

So it's not that the criminal laws governing oyster harvesting are unnecessary. The government has a role to play here. But criminal statutes are a blunt instrument for regulating fishermen. That's the wrong tool for the job.

Saturday, February 06, 2021

Crime, Bail, and the Media: A century-old recipe for error and injustice

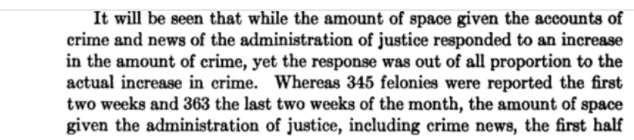

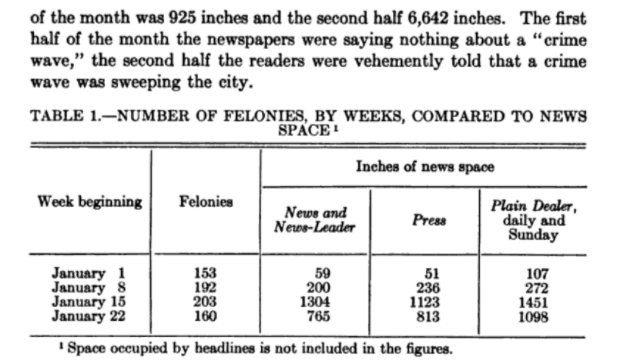

Recently, I ran across what appears to be the earliest quantitative analysis of media crime coverage in America in a massive, 700+-page document titled, "Criminal Justice in Cleveland: Reports of the Cleveland Foundation Survey of the Administration of Justice in Cleveland Ohio." On p. 544 of this behemoth, we find this remarkable assessment of a media driven crime panic over the course of one month in Cleveland and the predictable, and current-day-relevant policy results from this brand of journalistic malpractice.

During January and February, 1919, there occurred what was known as the 'bail bond expose.' ... It became known that a number of persons suspected or actually arrested and charged with crimes had been previously under arrest and released on bail. Special newspaper attention was given to the fact that bail was fixed by judges on the recommendation of the prosecutor, and in view of this power of fixing bail by recommendation the prosecutor was urged to demand higher bail.

Preston Chaney died of COVID-19 after more than three months at the Harris County Jail on allegations he stole lawn equipment and frozen meat. Two days later, Chaney’s court-appointed lawyer, who’d logged just two hours on his case, billed for additional work.

Chaney had a hold and was rejected for personal bail under Gov. Greg Abbott’s pandemic order banning the release of anyone with violent charges or prior arrests. Had the 64-year-old been able to scrape together $100, he could have waited for trial away from the packed downtown lockup.

This was an avoidable death. Tuff on crime demagoguery has consequences. Local media, particularly in TV news, deserve a share of the blame for it.

Tuesday, February 02, 2021

Deep in the Weeds: Sandra-Bland data provides first-ever detail on scope of arrests, searches at Texas traffic stops

Your correspondent needed to pull some data this morning for other purposes, so let's dump some interesting, previously un-reported tidbits here.

The Scope of Texas Traffic Enforcement

In 2019, Texas law enforcement officers reported making 9.7 million traffic stops in racial profiling reports submitted to the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement.

About 3.9 million of those stops, roughly 40%, resulted in citations. (For reasons no one fully understands, citation totals have been falling for more than a decade.)

Agencies reported someone was arrested at 306,962 stops, or at 3.2% of all traffic stops in 2019.*

A majority of those arrests (168,951) related to penal-code violations. In many cases, officers discovered contraband that triggered these arrests. Seventy percent of all contraband found was drugs or drug paraphernalia.

Avoidable Arrests

Roughly a quarter of arrests at traffic stops (73,911) were for outstanding warrants. These are folks truly suffering from the Debtors Prison Blues:

In addition, 21% of arrests at traffic stops were for Class C misdemeanors (64,100), mostly moving violations and a few arrests for breaking municipal ordinances. These are the arrests that would be eliminated under the George Floyd Act (and should have already been eliminated: similar language was pulled out of the Sandra Bland Act before it passed in 2017). Here's a breakdown of arrests by type:

Police reported using force at .6% of stops, or 60,034 total times in 2019, but use-of-force rates by department varied widely.

Why Do We Search?

In aggregate, Texas cops conducted searches at about one in 20 traffic stops statewide (5.1%), discovering contraband a bit more than a third of the time (34.5% of searches resulted in contraband "hits."). Roughly a quarter of all traffic-stop searches in 2019 (26%) were conducted based on "consent searches" in which the driver gave the officer consent to search. Another 35.8% happened because the officer observed probable cause; and about a third were "inventory searches" or "searches incident to arrest."

This data from the Sandra Bland Act casts new light on what previously was a largely opaque process illuminated only occasionally and momentarily by the release of bodycam video or civil litigation. But the plural of anecdote isn't "data" and until recently, we didn't have department-level numbers to provide insight into local, much less statewide traffic-enforcement practices.

Opportunities

As I look at this heretofore-unreported data, it reinforces the key opportunities for decarceral legislation aimed at traffic stops: The Sandra Bland/George Floyd Act language would eliminate 21% of traffic-stop arrests. Reducing the number of warrants under the Omnibase program would shrink another sizable chunk.

Finally, if drugs make up 70% of contraband found, Grits would expect most of that to be marijuana. So drug-related penal-code arrests could also go down when we see 2020 data because of the Great Texas Hemp Hiatus. (Grits would prefer to see marijuana straight-up legalized, but even tamping down arrests via the new hemp law is an improvement over prior practices.)

Traffic stops are a major, front-end driver of county jail admissions. So anything that reduces how often they result in incarceration also reduces pressure on local taxpayers and avoids adding people to the jailhouse petri dish who might be exposed to COVID.

The newest round of "Sandra Bland" data comes out March 1st, and this time, problems with racial categorizations are supposed to have been fixed. So reporters and researchers should mark that date on their calendar (some agencies have already begun to submit) and set aside time for a deeper dive when that information becomes available. There's a lot of good stuff there.

*A handful of small agencies reported that they arrested someone at every traffic stop. This was clearly an error and those agencies' arrest totals were excluded from this calculation.

Monday, February 01, 2021

Beyond "aid" to law enforcement: Crime-lab independence speaks to scientists' differing priorities from cops

Austin's city manager Spencer Cronk for years has balked at making the crime lab independent. Now that the community has made such "decoupling" a part of "reimagining" the police budget, he has had little choice but to embrace the idea. But he's doing so in the most tepid, pro-cop way imaginable.

Here's the proposed ordinance, which places the crime lab under control of the city manager with no independent oversight board. Check out the vision statement for the new agency, then let's compare it to Harris County's forensic science center.

The Forensic Science Department shall be engaged in the administration of criminal justice in support of state, federal, and local laws, and shall aid law enforcement in the detection, suppression, and prosecution of crime. In carrying out this purpose, the Forensic Science Department shall:

• Conduct objective, accurate and timely analyses of forensic evidence supporting the administration of criminal justice, and perform related services;

• Allocate substantially all of its annual budget to such criminal identification activities; and

• Be responsible for the following services in support of criminal justice: crime scene investigation; evidence management; firearm/toolmark examination; seized drug analysis; toxicological analysis; latent print examination; DNA analysis; and related forensic services as may be now or later developed for public safety purposes.

• Establish such policies, management control agreements, and procedures as necessary to carry out its purposes and activities stated above.

By contrast, here's the Mission/Vision statement for the Harris County Institute of Forensic Science:

The Mission of the Harris County Institute of Forensic Sciences is to provide medical examiner and crime laboratory services of the highest quality in an unbiased manner with uncompromised integrity.

Vision

To provide consistent, quality death investigation and laboratory analysis for the benefit of the entire community.

To create a technological strongpoint for legal agencies to facilitate justice in criminal and civil proceedings.

To establish an academic environment for training in the field of Forensic Science.

Notice the difference? In Harris County, the "mission" is about quality science that benefits everyone. In Austin, the proposed mission is to "aid law enforcement in the detection, suppression, and prosecution of crime" and to "Allocate substantially all of its annual budget to such criminal identification activities."

If the department allocates "substantially all" of its budget to "identification," will it be able to implement the sort of quality-assurance systems needed to prevent false convictions? Will the department spend adequately on scientists' professional development? They haven't in the past. Nothing in the proposed ordinance reflects any of the myriad problems that put the lab on the "decouple" list in the first place.

In the Harris County example, scientists are encouraged to be scientists; in Austin, the city manager views them as an agent of law enforcement.

These are quite different approaches, reinforced by different governance structures: The Austin City Manager has suggested the crime lab report to him just like other departments. By contrast, the Harris County lab director reports directly to the county commissioners court. The Houston lab - itself spun off from the police department - has its own independent board.

Several local civil-rights and victim advocacy groups are petitioning the City Council to change the proposed mission statement and "activities" before this comes to a vote on Thursday. The same groups aim to champion changing the lab's governing structure soon after the new department is created.

.jpg)