Local, mainstream media coverage of the Austin police union contract - which was

rejected Wednesday night after a dramatic, 8-hour special-called city-council meeting - has been disturbingly bad. People whom I've considered good reporters on other topics have written pablum-filled junk on this one. For the most part, journalists appeared to go out of their way to avoid reporting factual information when it was provided by advocates or movement leaders, and instead chose to report spin and outright falsehoods from the police union and (to a slightly lesser extent) police department management.

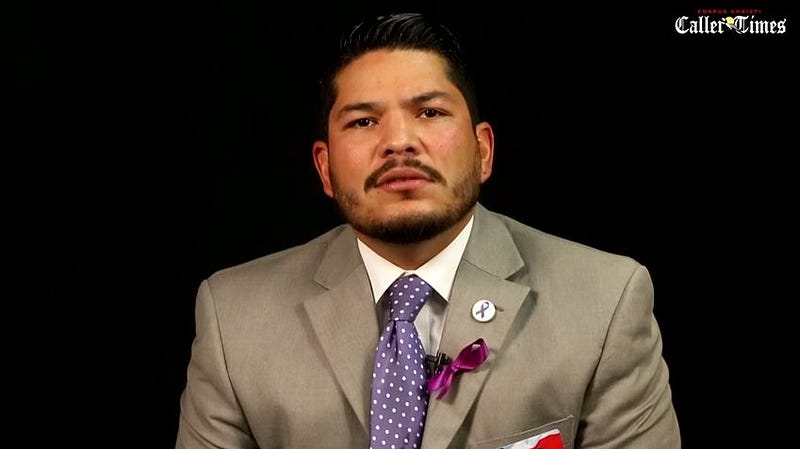

With the exception of Michael Barajas at the Texas Observer, most reporters leading up to the council vote portrayed opposition to the contract as coming from only a handful of critics, often suggesting Austin Justice Coalition's Chas Moore was the sole, vocal opponent.

The Austin Statesman at one point

estimated that "several" activists opposed the contract, and after the council vote, a

local TV station said "dozens of community members" opposed it. In reality 20 different organizations signed on against it - including Travis County Democratic Party precinct chairs voting unanimously to recommend rejecting it - and more than 220 people signed up to speak against the contract Wednesday night, with 54 police officers and their family members signed up for it, the Mayor announced at end of the meeting. (The total actually speaking was lower on both sides in the end because many people donated their time to others or had to leave before their name was called.)

Beyond simply downplaying the size of the movement, a lot of false information has been propagated because reporters simply accept official sources uncritically and do not seek out alternative sources or views. Sometimes these official sources lie, but the reporters aren't performing even the most basic legwork to fact check those falsehoods.

To take the most immediate example, Chief Brian Manley and the police union have been saying - and the Statesman repeated the line as the top news about the contract - that

up to 300 veteran officers could retire if the contract was rejected. These were official falsehoods being promoted as a scare tactic.

And now that the contract has been rejected?

Reported KXAN-TV, police union president Ken Casaday said, “We’re expecting somewhere between 25 and 50 to leave.” So between 1/12 and 1/6 of the number he was estimating a week before. While KXAN reported the new, much smaller estimate, the headline did

not not say, "Far fewer officers will retire than expected." Instead, they doubled down on the original falsehood with the scary headline, "Some APD officers already putting in for retirement after contract was stalled." Not one media outlet has called out police management or union officials on their earlier misrepresentations. Instead, they're collaborating in a spin campaign.

So, since we can't expect local reporters to do it, let's go ahead and answer the question, "Is 25-50 retirements significant?" It turns out, according to the

annual report from the Austin police officer retirement system (p. 133),

56 officers retired in 2016, and 71 retired in 2015. So even minimalist reporting, checking the most basic facts about the topic in easily accessible public sources, would show that these numbers of retirements aren't really a big deal at all. Austin cops with enough years in to make them eligible for retirement make upwards of $120K per year, including overtime - among the highest paid in the nation. There aren't other jobs, anywhere, where they can make that much, so most will stay put.

Reporters should aspire to be more than stenographers. These are the sorts of failures by the journalism profession which, on the macro level, brought us Donald Trump: Quoting public figures without fact checking their comments, refusing to report factual information because it doesn't come from a preferred source (usually the government), and focusing on personalities instead of issues.

Austin journalists who've covered the police contract for the most part should be embarrassed. They never provided the public with a

meaningful assessment of the issues at stake, despite

ample documentation, numerous community meetings, public forums and other

opportunities to cover them. A massive, city-wide debate has taken place on this topic over the last six months, and it has occurred almost entirely

without the MSM playing any meaningful role.

You could read everything written in the MSM about the contract before Wednesday's vote and have at most a minimalist understanding of the issues contract critics raised. Only one

Statesman article, in October, even listed the eight accountability measures demanded by AJC and its allies. From that story, here's the most detailed MSM discussion Austinites ever got of the policy questions that ultimately caused the police-union contract to be shot down:

The resolution suggested, as Austin activists have for months, eight different reforms to the police contract: reforming the department’s 180-day rule, which limits the amount of time the police chief has to discipline officers; eliminating automatically downgraded suspensions; giving subpoena power to current oversight bodies; allowing misconduct to be considered equitably in promotions; allowing citizens to make complaints online or over the phone; allow the police monitor to initiate investigations even without a citizen complaint; stop permanently sealing records related to police misconduct; and releasing records without removing content.

And I should give those reporters credit: No one else except Barajas ever even listed them. However, each of these amounts to a complex debate into which the general public cannot meaningfully enter without much more detail and context than what's being provided. No media outlet ever discussed them at length, much less linked them thematically to the various cases which inspired the recommendations in the first place. Police union positions, however, were quoted over and over again.

As a result, Statesman readers, and consumers of all other local MSM, were essentially shut out of the real conversation. Instead, the most important debates took place online, in hundreds of one-on-one conversations behind the scenes, and in numerous public forums to which our journalist friends had access, but of which they chose not to avail themselves. Most reporters took the lazy way out, filling their stories with quotes from the police union and the city and using their authority to marginalize critics.

At times, it almost seemed intentional. More than a few of these reporters have shown they're better than that in other settings. In this instance, though, the local Austin press corps chose to serve as shills and propagandists for the powers-that-be, missing the story about an eruption of public discontent over a major public policy issue until after the fact. It was a sad and disappointing display.

.jpg)