And yet, facts persist. Sigh. Let's talk about one that nobody in the political class wants to believe, and that will certainly only bring Grits grief for even mentioning: The just-released National Crime Victimization Survey - one of the two main measurements of crime in the United States - found that, "From 2019 to 2020, the total violent victimization rate declined 22%, from 21.0 to 16.4 victimizations per 1,000 persons age 12 or older." Burglaries and trespassing complaints declined, the survey found. And the decline was especially pronounced among youth age 12-17, for whom violent victimizations decreased 51%.

Does that jibe with the breathless news coverage about crime you've read in the last year? Of course not. The decline in violent victimization won't attract viewers/readers the same way as "Be afraid, killers on the loose," so it won't be reported. Compare this to how the increase in murders played out in the press last year.

As John Pfaff observed on Twitter, this news reinforces the extent to which the reported crime increase being touted near-daily in the press has been largely about homicides. Assaults and violent victimizations overall were down last year, according to this metric, particularly in suburban areas. Simple assaults were down, but also more serious ones. Firearm victimizations, which in this survey includes pointing a firearm as well as firing one, declined from 481,950 in 2019 to 350,460 in 2020. Burglaries were down 19%.

The NCVS is one of two main, national crime measurements in the United States. The "Uniform Crime Reports" (UCR) count crimes reported to law enforcement agencies, while the NCVS surveys crime victims to include crime victims who didn't report to police.

The NCVS is especially important right now because of changes to UCR data. Without going too deep in the weeds, the feds are shifting to an incident-based reporting system that supposedly is more accurate but results in data that's not an apples-to-apples comparison to what was reported before. Plus, many smaller agencies haven't yet made the switch. So for the next few years, it will be problematic to judge crime trends based on these data: They'll be establishing a new baseline that's not comparable to the old numbers.

The NCVS, by contrast, is still performed as it was in the past, though in-person interviews were halted last year for a time bc of COVID. Moreover, the story it tells corroborates UCR data on crime beyond homicides: News reporters and criminologists have puzzled that murders increased but reports of other types of violent crime went down. The NCVS confirms that crime victims simply were victimized less, not just that reporting went down because of distrust of police (or whatever reason one wants to assign).

So many in law enforcement have taken the recent murder spike as an excuse for a money grab, there's little reason to hope public policy might adjust to reflect actual, in-real-life crime data. So Grits offers up the NCVS analysis without any real belief that it will convince anybody of anything. Everyone will just look at it for evidence that confirms their priors, cherrypick that, and move on.

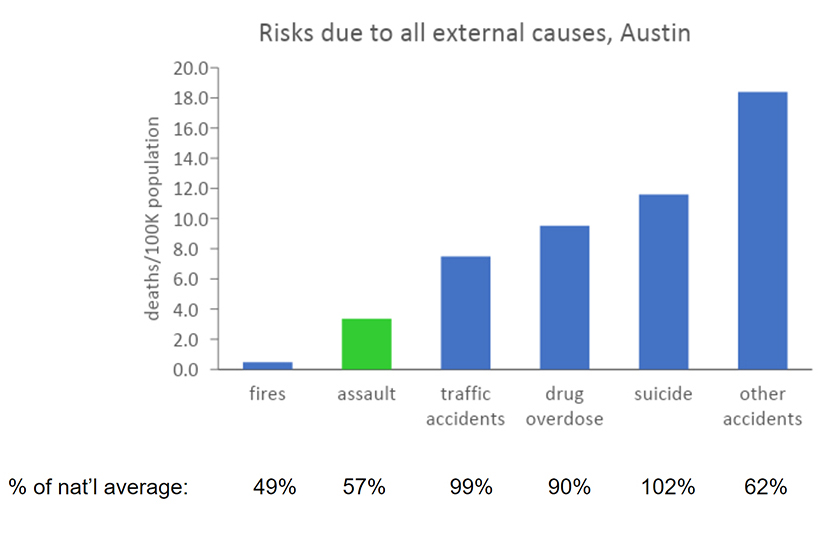

In the context of declining violent crime victimization, it's worth revisiting recent research from Dr. Bill Spelman at the UT LBJ School. He analyzed the major risks of death for Austinites and found murder was a far less salient risk than traffic deaths, suicides, or drug overdoses.

Anyone truly concerned about "public safety" in this town would, by any reasonable measure, be chiefly concerned with the causes of death on the right-hand side of this chart. But we spend most of our time in city politics and a majority of the city budget on the causes on the left hand side. It's exhausting. And stupid. And I don't know if it can or will ever change.

.jpg)