police focused on other duties, jails avoided extra prisoners during COVID, court caseloads shrank, taxpayer-funded hemp testing was (largely) avoided, and counties avoided paying for some indigent defendants’ lawyers. Commercial hemp was legally harvested and sold. And nobody cared. Not really. There has been no hue and cry. If anything, the public hue and cry favors full-blown pot legalization.In the meantime, more than 40,000 Texans who would otherwise have been arrested in FY20 avoided prosecution for pot possession, which meant they not only avoided a criminal record but also had more money to support their families when the COVID crisis hit. Would anyone be better off if 40,000 extra families, many of them already losing income from a virus-caused economic depression, were saddled with fines, court debt, probation and drug testing fees, etc.? Not at all! Everyone is better off because those prosecutions didn’t occur.Aggressive marijuana enforcement does more harm than good and the natural experiment conducted in Texas over the last year shows that there are no negative consequences when it suddenly stops. There’s no need to “fix” the hemp law or spend millions more on specialized testing.

Thursday, October 29, 2020

Hemp law radically reduced pot prosecutions in Texas: Don't go back

Monday, October 26, 2020

A chance to expand police oversight: Why Texas should begin charging cops and jailers licensure fees

But a new document from the Legislative Budget Board shows that TCOLE may need to begin charging licensure fees just to keep its funding at current levels. Here's why:

Since 2004, TCOLE has funded most of its activities using General Revenue–Dedicated Funds from Account No. 116, which is composed of consolidated court fees collected pursuant to the Texas Local Government Code, Section 133.102. Currently, multiple agencies spend funds from Account No. 116, including TCOLE, the Comptroller of Public Accounts, and the Department of Public Safety. In addition, employee benefits are paid from this fund. The amount of revenue collected has been decreasing for at least the past 15 fiscal years.

Check out this chart showing the rate at which this account has been outspending intake:

So the account balance is scheduled to drop below expenditures by the end of the next biennium, meaning TCOLE and other agencies funded by Account 116 must turn elsewhere for funding. Or as LBB put it, "Without replacement, the loss of this funding would halt the majority of TCOLE operations." In that light, for TCOLE, charging licensure fees makes loads of sense.

LBB suggested four options for raising revenue for Account 116, but none of them involved licensure fees. That's a mistake not even to consider it. The people who license doctors, lawyers, plumbers, etc., are all financed via licensing fees, why not police and jailers?

Grits wanted more money for the agency to facilitate more oversight and compliance functions. E.g., in FY 2019, LBB reported, TCOLE audited 770 agencies for "law and rule compliance" and found "deficiencies" in 349 of them. It's great that they're catching violations after the fact, but that's an awfully high rate of deficient audits.

Moreover, Texas is one of only a handful of states where the peace-officer licensing agency can't revoke licenses of officers for serious misconduct. Here, we require them to be convicted of a felony first, which almost never happens. But a decertification program would require resources, particularly for attorneys, and licensure fees are the most obvious way to pay for them.

At the moment, TCOLE's budget runs around $4 million per year. Assuming a) a 95% payment rate, and b) licensure fee rates of $50/year for police, $40/year for 911 operators, and $30/year for jailers, Grits estimates about $4.9 million could be generated. One could fiddle with those fee amounts to adjust that figure up or down.

There are also nearly 3,000 agencies authorized to provide training who could also be asked to pay for the privilege. At $500 per year, ~$1.4 million could be generated from that cohort.

If Texas must begin charging licensing fees, anyway, it should do so at a level that lets the state expand oversight functions, not just keep up the status quo.

Related: See Grits' discussion of TCOLE's Sunset review.

Police Monitor: Austin police commanders ignore misconduct when they disagree with department policy

It sounds like commanders substituted their own personal judgments for policy in issuing such a light sentence: "Should an officer’s commander disagree with any section of [APD policy] ... In no scenario should anyone in an officer’s chain of command impart their opinions about policy through the disciplinary process," the OPO advised.

The OPO also expressed concerns about how investigators treated civilian witnesses, finding it necessary to warn that Internal Affairs investigators "should use caution with both the tone and subject matter of their questions and avoid questions that could discourage civilians from participating in current or future investigations."

The OPO further warned against IAD using "leading questions" with civilian witnesses and said their use threatened the "integrity of investigations."

They also pinpointed a pattern of manipulative questioning: "Interviewees should not be asked whether they believe that certain conduct meets a word's definition, especially when that word has a particular meaning in APD policy, without first having the word defined for them."

Thank heavens for the OPO! Without that agency (and the police-contract adjustments in 2018 allowing for greater transparency), the public, and for that matter the Austin City Council and city manager, couldn't know about such problems.

Thursday, October 22, 2020

Four stories let public peer into soul of Houston justice system

Monday, October 19, 2020

"I wonder why black folks don't want to join Waco PD?," cops telling on themselves in social media, SWAT excesses in Nacogdoches, and other stories

Talk is cheap when it comes to police accountability: Joe Gonzales, the DA in Bexar County, Texas, seems like a nice enough fellow. But it's time for more than promises that his office will scrutinize officer-involved shootings more closely in the future. That implicitly reminds the public your office wasn't doing so before, while failing to expressly acknowledge it or apologize for the failure. We're in a "show, don't tell" moment when it comes to law-enforcement officials reassuring the public they will punish police misconduct. People won't believe it until it actually happens.

Disrespectful: The level of armed surveillance at George Floyd's funeral was unnecessary:

Vice News reports police in Pearland, Texas, requested the presence of Border Patrol snipers at George Floyd’s burial on June 9 and gave them permission to use deadly force as members of the militarized tactical unit known as BORTAC surveilled funeral attendees. Records obtained by Vice also reveal an FBI surveillance aircraft was flown over the burial to monitor for so-called violent agitators. That day, at least six sniper teams were in place on rooftops and authorized to open fire.

SWAT-ing episode exposes police overreaction: Grits is late to discussing the SWAT-ing incident out of Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, but setting aside her classmates' culpability (and calling the cops on your friend is an asshole move) the idea that cops brought in the SWAT team to a dorm over a young woman with scissors speaks to a policy of needless escalation. Even if you accepted the false premise fed to police, their response wasn't warranted.

Hidden tragedy: Read the story of the first man to die of COVID in the Dallas County Jail.

Telling on themselves: An 18-year veteran Fort Worth Police Officer was fired after sharing on social media a meme of a black man in a coffin accompanied by the words, "Stop Resisting!"

Not a crime: Read the case against jaywalking being a crime: Grits agrees with roughly 95 percent of this analysis, though some of this history was new to me. But I've long opposed using criminal law to punish average people for the failures of traffic engineers.

People with criminal records need housing, too: After the public comment period was over, we finally got some MSM coverage of the new rules restricting access to supportive housing for people with criminal records. See prior Grits coverage.

I wonder why black folks don't want to join Waco PD? Read about Waco PD's difficulties recruiting black officers - or really, anybody - to join their ranks: "a police exam might draw close to 800 applicants 20 years ago, and 300 a decade ago, but that has dropped to about 100 in recent years." Readers may recall Waco PD topped the statewide list for agencies arresting the most people at traffic stops; in 2018, cops in Waco arrested about 4.5% of all drivers they pulled over.

Better late than never: Fact checkers at PolitiFact say Gov. Greg Abbott's assessment of crime in Austin was "mostly false." But it shouldn't have taken a separate "fact checking" team to report that. It was false when he first said it and should have been reported that way from the get go.

Varieties of Police Oversight Systems: For anyone interested in the pros and cons of various police oversight systems presently in use, check out this overview from the National Association of Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement. Fascinating stuff: Every decision regarding how to set one up involves sometimes-unexpected tradeoffs. Related: A 2016 guidebook for implementing "new or revitalized police oversight."

Friday, October 16, 2020

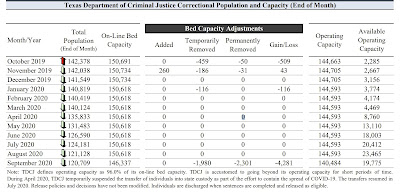

Texas prison pop reaches 21st-century lows, but jail populations rising again

Perhaps also contributing: a substantial, reported crime decline this spring and court slowdowns, including most not setting felony trials, thus possibly delaying plea bargains.

By contrast, Texas county jails statewide had reduced populations by about 15% this spring, but as of October 1st are back to pre-COVID levels.

Both juvenile commitments to youth prisons and certifications of youth as adults also declined in 2020, reported the Legislative Budget board.

Thursday, October 08, 2020

Rangers rule police shooting 'murder,' searches at traffic stops mostly fruitless, Sheriffs behaving badly, and other stories

- I'm not sure I've ever heard of the Texas Rangers announcing a shooting by a police officer constituted "murder," as they did in the case of Wolfe City Police Officer Shaun Lucas' killing of Jonathan Price. Either this summer's events have changed attitudes at DPS, the facts of case are especially egregious, or maybe both.

- Overwhelmingly, most searches at traffic stops are fruitless fishing expeditions. At the Houston Chronicle, Eric Dexheimer and St. John Barned-Smith dug into the data on contraband hit rates, newly available from Texas' Sandra Bland Act, and took aim at trainers teaching cops "deception detection."

- Read the case for ending binding arbitration for fired police officers.

- Ten people died in the Tarrant County Jail this year and a woman gave birth without the jailers noticing (the baby also died). Now Sheriff Bill Waybourn is up for reelection. Michael Barajas at the Texas Observer took apart his record.

- The Sheriff in Fort Bend County is running for Congress and taking heat for his record of on-the-job misconduct.

- The Texas Indigent Defense Commission has created a new primer for counties that want to create a Public Defender office.

- The Vera Institute of Justice has published a massive new report analyzing 911 call centers and suggesting reforms. More on this after I've had a chance to read it; perhaps it will help inform Austin's push to make the local call center independent.

Pernicious housing rule would worsen homelessness, make Texas less safe

TDHCA has suggested forbidding access to supportive housing for two years for anyone convicted of a nonviolent felony, for three years for certain offenses involving guns, retaliation, or obstruction, and imposing lifetime bans for people convicted of sex offenses, any "murder-related offense," sexual assault, or arson. Even a Class A misdemeanor would get a one-year ban.

What's the point of this except to exclude people from supportive housing options who would otherwise end up homeless? Would we be safer if felons, sex offenders, etc., are all desperate and living on the streets, or if they're housed with services and support that give them a chance to turn their lives around?

In a story I'd missed when it came out, the Houston Chronicle reported the agency has no "statistics showing there was a crime problem at TDHCA-backed housing" and does not even track that information. So this is clearly a leap-before-you-look situation.

Grits first wondered if this was proposed to undermine anti-homeless initiatives in the big cities, sabotaging them so the governor could later say they didn't work. Then a rumor reached your correspondent saying the rule may be a favor to a donor who opposes a specific development. In the Chronicle story, TDHCA said they're responding to complaints, but wouldn't say by whom. Who knows where it came from?

What we do know is that felons leaving TDCJ already struggle mightily to find housing, particularly those with special needs who would most benefit from supportive housing options.

This proposal makes Texas less safe and should be rejected, adamantly, by the TDHCA board.

To communicate with TDHCA about the proposal, email comments to htc.public-comment@tdhca.state.tx.us. Deadline is tomorrow (Friday, Oct. 9) by 5 p.m..

MORE: See related Texas Tribune coverage.

Monday, October 05, 2020

With one, unanswered question, Chris Wallace debunked weeks of Texas media coverage on Austin, Fort Worth, crime trends, and partisanship

Trump ignored the question's premise, doubled down, and blamed Democrats, while Biden never returned to the Fort Worth example. But Mayor Price says her phone began to blow up almost immediately. She responded the next day by distancing herself from the premise, championed by President Trump and Governor Greg Abbott, that crime is a partisan concern. "Not a party issue," she declared. "It just isn't. We always say potholes don't care what party you are. Crime certainly doesn't care what party you are."

Well, gee, Mayor, it would have been great if you'd been so non-partisan and pot-holish when you sat next to Governor Abbott while he demagogued against the Austin City Council, whose citizens are murdered at significantly lower rates than Fort Worth's. Don't blame the media for picking up on that: What's good for the goose is good for the gander. Price released this data comparing murder rates in Texas cities:

By Grits' calculation, if Austin's murder rate this year were as high as Fort Worth's, we'd had seen 74 murders instead of 34. So why hold a press conference in Fort Worth to tell Austin how to keep safe?Report from Houston Policing Task Force should launch broader conversation

The Task Force recommended more than Grits expected but less than I'd hoped. These are very much reformist approaches that contemplate improving systems addressing police misconduct, not reducing police interactions with the public overall. (The one exception is their endorsement of Houston PD availing itself of a 13-year old statute allowing police to give tickets instead of arresting for certain minor offenses.) That doesn't mean they're not important reforms, they're just not radical ones.

There's a risk a report like this with its 104 deep-in-the-weeds recommendations will be briefly acknowledged in the press, then shelved. But it could/should be the starting gun for a broader discussion across many subjects, not the final word on reform. Grits' hope is that these commentaries contribute to that conversation in Houston. It's much needed.

Saturday, October 03, 2020

Houston Mayor's Policing Task Force Recap, Part 3: Mental-health first response, What counts as diversion?, the 'all-purpose panacea promoted by people who oppose policy change,' and other stories

Mental-Health First Response

In Austin, Dallas, and elsewhere across the country, one of the approaches to displacing police from non-law-enforcement tasks has been mental-health first response, where many clients do not ask for a law-enforcement presence and end up in involuntary detention, more often than not, because police don't know what else to do with them. Adding insult to injury, when cops drop them off at the emergency room, they get credit for a "jail diversion"!

The Task Force found that "Diversion of mental-health-related 911 calls at the call center level is the earliest point of diversion before any law enforcement involvement. Since the beginning of the [counseling] program, CCD [Crisis Call Diversion] diverted more than 4,902 calls from law enforcement response and saved the equivalent of 7,353 hours of police time (March 2016 to May 2019)." The Task Force recommended funding 24/7 counselors to boost the diversion rate, as well as boosting the number of Mobile Crisis Outreach teams (civilian medical folks who respond to MH crises in the field), and tripling the number of HPD's CIRT teams, which are police officers teamed with mental-health practitioners.

The Task Force endorsed a legislative proposal folks in Dallas and Austin have been clamoring for as well: Amending state law (Chapter 573 of the TX Health and Safety Code) to allow health care professionals to handle decisions related to emergency detentions. Right now, only police can do so, and that law is a barrier to removing law enforcement from the equation in non-criminal mental health calls.

Mental health cases are a growing part of HPD's case load, as they are all over the state. In an article on CIRT teams, the Chronicle mentioned that, "In Houston, encounters between police and people with mental illness ballooned over the last decade from 23,913 mental-health calls in 2009 to 40,884 in 2019." That means that the Crisis Call Diversion handles a rather paltry 3.8% of calls.

The Mayor's task force claims HPD's CIRT teams focused on mental-health cases has a 95.9% rate of "diversion from jails." But that's a miseading figure. Fewer than one in four calls are resolved at the scene; in all other instances, somebody is taken away, usually against their will, and sometimes against the wishes of their parents, guardians, or care givers.

It's time for H-Town to challenge itself to substantially increase the share of mental-health calls met with a non-police response. A major goal should be boosting that "resolved on scene" number from less than 25% to 2/3 or more, reserving "emergency detention" for situations where a person poses a danger to themselves or others. Those criteria may include abusive behavior toward family and there may be good reason to detain any given individual (so spare me the parade of anecdotes in the comments, I get it). But in a huge number of cases there is not; too often, cops take someone based on a "better safe than sorry" logic. After all, the hospital/ambulance bills aren't going to show up in their mailbox months later.

Domestic calls: Do all of them need a cop?

The Task Force endorses a pilot program at HPD for intervention with high-risk domestic violence victims called DART (Domestic Abuse Response Team), which pairs officers with a victim advocate nurse. The pilot has been ongoing since January 2019, operating three nights per week (7pm to 3am) in three HPD districts. No information on how much it would cost to expand.

For that matter, I'd love to see any outcomes or research based on this pilot, comparisons to control groups, etc.. When I searched on the HPD website regarding the program, I only found one responsive web page: This flyer. If it's been going for nearly two years, one would think there'd be something out there.

When agencies do pilots, Grits believes they should always budget a research and data collection component. Domestic violence policies and police responses have always been all over the map. Maybe this is a great program; maybe other approaches would be better. When experimental programs are tested, somebody should be tasked with reporting on what they're doing, including any relevant metrics. Even better: Evaluating the program compared to a control population. That doesn't appear to be have been done yet for DART.

Regardless, Grits remains unconvinced that police need to go to every domestic disturbance call, even as security, as described in the DART program. There must be a response, and if a cops are needed, they should be called. But once the cop engages in violence or pulls their gun, that trumps clinicians' authority or decisions. Sending them only when needed reduces the chances that happens.

Indeed, one can make an argument that cops are simply the wrong messengers on this topic, as our pal Jessica Pishko recently reminded:

Other studies have found that police themselves are often the perpetrators of domestic and sexual violence, rendering them undesirable as a source of help, particularly for women of color who experience much greater rates of violence, including sexual violence, from police. Interactions with the police can also exacerbate existing conditions, like economic instability or trauma.Pishko quoted law prof Aya Gruber expressing a sentiment your correspondent has held for some time: "victims may be making a rational choice when they decline to testify against their abusers. 'Domestic violence prosecutions have little benefit to women and in fact can harm them,' she explained, 'but the prosecutors are very convinced they are saving women’s lives.'"

Task Force: Decriminalize prostitution! But make them work in criminalized environs.

Grits didn't foresee the Mayor's Task Force recommending that prostitution be decriminalized. That said, they weren't exactly suggesting the re-establishment of the city's red-light district: They still think the state should to prosecute "pimps, brothel and illicit massage parlor owners and managers, sex tourism operators, and sex buyers." But right now, they declare, "Law enforcement is arresting the wrong people."

Here's the oddity: Clearly they consider most prostitutes victims who deserve protection. Different folks feel differently about that, including sex workers, and I'm not trying to launch that debate. But I do question the virtue of claiming to "decriminalize" prostitution and then criminalizing everything about the industry except service provision.

In the age of the internet-personal ad, many prostitutes operate individual sole proprietorships without a formal "pimp" or brothel. For them, the Task Force's distinction doesn't make a difference.

If we're now going to express sympathy for prostitutes, then let's be clear: The biggest dangers they face all stem from the government banning their services and forcing members of the Oldest Profession to provide their wares in a black market. The sole proprietor of the liquor store may rely on police for protection; the sole-proprietor prostitute seeking security must turn to a pimp, which is an inherently unhealthy partnership.

Training: The all-purpose panacea promoted by people who oppose policy change

Look, I'm all for good police training. Indeed, much of what I've learned about police practices (and jailers, and prosecutors, and defense lawyers, and district judges, and appellate judges, and forensic analysts, etc.) has come from attending their professional training sessions, conferences, and CLEs over many years and/or reading training materials (plus chasing down items from their footnotes) from those events. While, between my illness and COVID, 2020 has been a dry spell, in the past I might normally attend several such events per year, including many that put me in rooms filled with police officers. Frankly, I've never had a bad experience doing that and highly recommend it.

That said, having worked on police reform now for more than 25 years, here's Grits' view: "More training" is the first thing reform opponents suggest whenever substantive reforms are proposed. It's always the first "reform" suggested and, as soon as it's implemented, reform opponents push hard to stop there. Every time. Some of the trainings on implicit bias and racial equity in particular appear to have little effect on outcomes. Grits didn't consider it good enough a quarter century ago and it's certainly not good enough now.

Yes, change your policies, train on the improved ones, and consistently, effectively punish officers who fail to follow them. That's how you change departmental culture. But training alone won't help.

Reflections on Mayor's Task Force Recommendations

Having now gone through the entire report, what to make of it as a whole? There are moments where it is bold, for example, recommending changes to the 180-day rule and insisting officers suspected of misconduct should be questioned at the beginning of the investigation process. And I was excited to see the recommendation that un-redacted bodycam video should be released, though I don't agree to limiting that to critical incidents.

Similarly, the suggestions that 1) Houston PD create a complaints database and 2) publish an annual report on disciplinary actions against officers, would constitute a major leap forward in transparency for the department. But it falls short of what's needed: Police departments also need to begin publishing data and detail about use of force incidents in online databases where researchers and the public can access them. Grits knows for a fact legislation requiring that statewide will be filed during the 87th Legislature, and the an executive order from Donald Trump mandated creation of a national database documenting "instances of excessive use of force."

Texas already has good data on police shootings and deaths in custody. That's the next step.

Grits remains less than confident they've figured out the right way to keep Houston cops from shooting people on mental-health calls or domestic disturbance calls. I'd prefer to see them working to expand the subset of those encounters at which police are absent entirely. They can always be called in if needed.

Other suggestions seem more like half measures that don't really get at the problems they hope to solve - redesign a website, issue a report on diversity efforts, etc.. All perfectly reasonable stuff the government must think about, but boring and unlikely to be decisive in addressing the problems.

Finally, I don't believe they've identified the right model for the Independent Police Oversight Board, potentially designing it to perform a fruitless, Sisyphean task that leaves them set up to fail. The Task Force acknowledged that the all-volunteer IPOB needs significant staff to do its job, and that more staff are needed to process complaints, both from the community and from officers themselves. Why not follow Austin's lead and create a full-blown Police Monitor to manage that staff, add value through regular reporting, and to advise the Mayor and Council on issues related to departmental conduct, discipline, and culture from an independent perspective?

Grits sees these Task Force recommendations as the beginning of a conversation, not in any sense the final word on what reform in Houston might look like. If all of them were implemented tomorrow, it would be a Banner Day for Criminal-Justice Reform. And yet, it would be insufficient. In just a few years, many of the same problems would arise.

This report had a great deal of crossover with recommendations from several city council members earlier this week, and was in a sense even more aggressive. Between them, they're a good conversation starter, but now the conversation must move forward.

Friday, October 02, 2020

Houston Mayor's Policing Task Force Recap, Part 2: "Let the 'good cops' speak!," toward a functional police-oversight system, changes to use of force and bodycam policies needed, and building trust through transparency

IPOB members’ recent support of the four HPD officers who shot Houston resident, Nicolas Chavez, 21 times confirms our belief that the IPOB’s culture must be fundamentally overhauled. It is distressing to the Task Force that the civilians put in place to hold officers accountable would defend these officers’ actions when even the Chief of Police himself said that he “cannot defend [the officers’] actions” and deemed their use of force “not objectively reasonable.”

Thursday, October 01, 2020

Task Force on reforming Houston police: Empower oversight board, remove civil-service barriers to accountability at #txlege, and have someone besides the DA prosecute police misconduct (Grits has a suggestion)

The Houston Chronicle reported that the Mayor asked for "a few days" to digest the report and meet with the task force chairman, sub-committee chairs, and council members before formulating a response.

Grits, however, has no need to wait. Let's dig into this report and see what's there. Obviously at 104 recommendations, we don't have time to discuss all of them. And some of them are rather small-time, anyway. But let's run through the big stuff, describing their recommendations with Grits' own annotations. This is Part One of what I anticipate will be a three-part analysis: I read the 150-page report so you won't have to! :)

Community Policing (yawn)

So-called "community policing" has always been a hustle. No one can define it and in practice departments interpret it as officers spending time hanging out with whomever instead of responding to calls or performing police work. As fear of crime has declined as the go-to driver of more police spending, "community policing" offers departments a new metric -- percent of time available -- to demonstrate that we always need more officers no matter what is happening with local crime stats. At HPD, Chief Art Acevedo uses the term "relational policing," but, "The Task Force believes it is similar, if not mostly the same." In other words, it's a buzzword intended to confuse with results that can't be measured. None of the recommendations here seem destined to reinvigorate this tired and fruitless approach, from giving cadets community tours, making them sit through more lectures, or having officers document "out of car engagements with civilians and/or businesses."

Updating promotion matrices to give points for community policing might be helpful, once there is a consensus on what exactly officers should be doing, but the report failed to discuss taking points away for officers with misconduct records. That might help, too. In 2017 legislation, Houston state Rep. Senfronia Thompson recommended deducting points for officers found to have engaged in misconduct. Perhaps it's an idea worth reviving?

I liked the "mobile storefront" idea, which was the final recommendation (#16) in the community policing segment. Most of the rest in this section seemed pretty lightweight.

Independent Police Oversight Board

Grits has never been a great fan of civilian-review boards because most of them are as worthless as the one in Houston. Austin's oversight board, along with the Office of Police Oversight (essentially a Police Monitor-Board model), at least has become a window into policing problems we've never had before. (Local press don't cover the complaints, but they're out there from a credible source, and advocates discuss them.)

The Task Force agreed with city council members who recently said they have "no confidence in the current format" of the IPOB. Its powers are truncated and it fails to perform even the duties it's been assigned, they concluded. (These recall the complaints of an IPOB member who recently resigned over the group's inefficacy.) The Task Force laid out three broad models of police oversight:

- Auditor/Monitor Model

- Investigative Model

- Review Focused Model

They recommended IPOB expand to 31 members and adopt an "investigative model," but Grits wonders, "to what end?" Their investigation results would not be part of the department's decision making process when it comes to disciplinary decisions. They have their own investigators for that in the Internal Affairs division. How will these investigations affect real-world outcomes, including policies and practices, much less in the individual cases they investigate?

Since it's been empowered to a) review previously confidential documents and b) publish sometimes de-identified results, Grits has found Austin's fusion of Monitor/Review models (to use the Task Force's nomenclature) gives advocates more empowering information than we had before. The oversight board here reviews cases with an eye toward recommending policy improvements, and the record they create was been a valuable tool for documenting problems in a way that city officials are able to hear. Requiring the Chief to respond in writing to civilian oversight recommendations has also helped.

The Task Force does recommend hiring dedicated, paid staff to support the civilian review board, including investigators who it hopes will have "subpoena power." (FWIW, I'm not sure what more they think they'll get with a subpoena beyond what they get by mandating access to the department's full file.) Regardless, having staff led by a dedicated Police Monitor's position, as Austin did, has the added benefit of creating a counterweight to the chief in the city bureaucracy on police-misconduct questions, where officials might not listen to part-time civilian volunteers. That's a big practical benefit and has been welcome change.

Legislative changes needed to civil service

The portion of the report which made your correspondent jump out of his chair and whoop with sheer delight addressed legal changes needed at the state or city level, but with particular focus on the state.

They want to change the much-derided 180-day rule in two ways - one significant, one not. For the uninitiated, state law and many union contracts say officers in civil service cities can't be punished more than 180 days after they commit a misconduct violation. The Task Force recommended changing this in two ways: 1) have the clock launch on the "date of discovery" of the misconduct instead of the date it occurred, and 2) change 180 days to 210.

The first change is significant; the second much less so, though the first change magnifies its impact. Together, they'd be an important reform. That said, make Grits Philosopher King and I'd say for police the rule should be a full year from the date of discovery.

The Task Force wants to fix another civil-service practice your correspondent has railed against for years: "Require officers involved in incidents in which their conduct is under scrutiny to make statements at the beginning of the investigation." As the Task Force noted on p. 34, "Current practice allows officers to defer making statements until after the investigation is complete and they can read the entire file," as well as review any body camera footage.

Imagine if in a regular murder investigation they waited to interrogate the suspect until s/he reviewed the investigation file with their lawyer: Unthinkable!

Who should prosecute police misconduct?

The Task Force believes the District Attorney has a "symbiotic relationship" with the police department, which results in an "inherent pro-police bias." Thus they think "an independent agency," unnamed in the report, should prosecute those cases instead.

This has been suggested many times before. Some iterations see special prosecutors appointed each time, though that gets expensive.

Speaking of which, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton has said he'd take the job, but I don't think anybody would trust him.

Grits has a suggestion I believe would be popular with everyone but Alex Bunin, the Harris County Public Defender: I think the Harris County Public Defender Office should take over prosecuting cops instead of the District Attorney.

I've given this a lot of thought: Bunin and his shop are respected, and they already have an oppositional relationship with the Houston PD. I can't think of another outfit that would care less about pissing off the union. They've got the talent in the office to do the job. Plus the commissioners court just expanded their budget.

Now, they may not want to do it. Many of those folks are life-long defense lawyers who chose not to go into prosecution for a reason. But sometimes, the person who doesn't want the job is exactly the right person to handle it responsibly. (They know what's required; that's why they didn't want it!) It wouldn't be that many cases by comparison to their usual docket and I believe they're the right crew to handle the job.

.jpg)