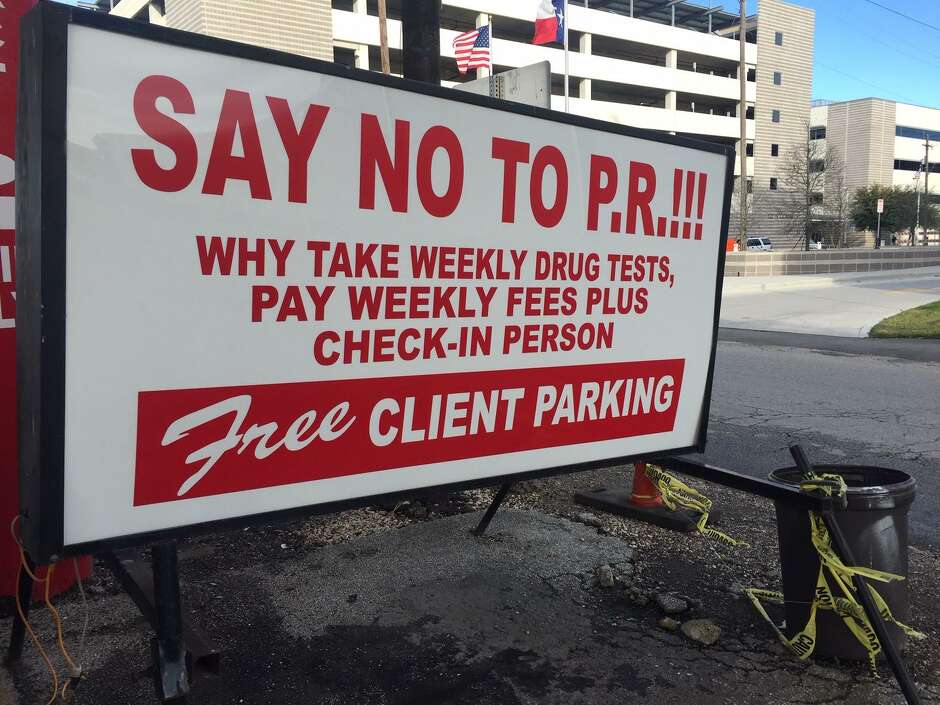

There are three centers of gravity in the bail debate: Governor Abbott, whose positions largely reflect those of the bail industry and tuff-on-crime political ideologues like Andy Kahan; the 5th Circuit, which has at least three Texas bail cases bubbling up in its direction which will establish a new constitutional floor for Texas bail policy; and reform advocates who want to end money bail.

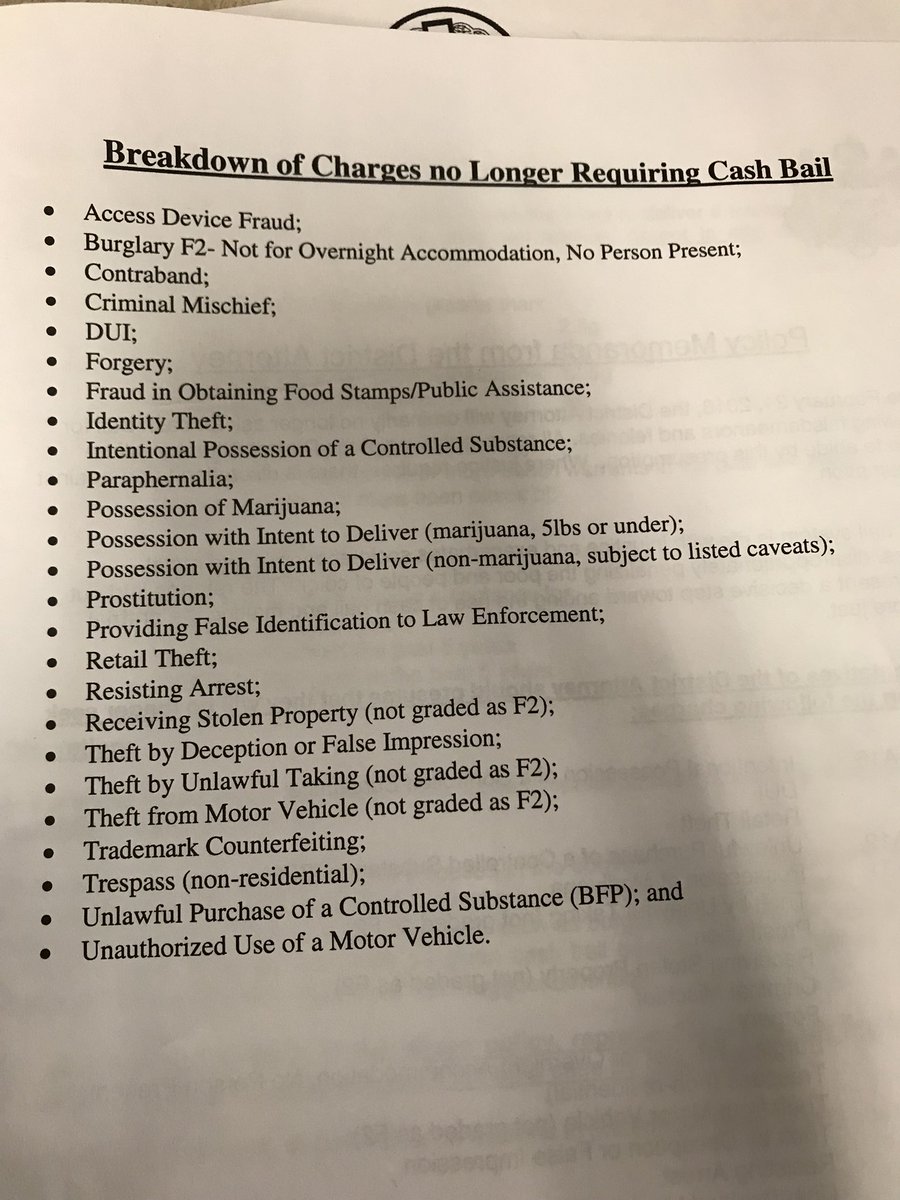

There are several dynamics that make a viable legislative outcome impossible in 2021. Advocates and the 5th Circuit cases are largely focused on bail issues surrounding indigent defendants and reflect concerns about excessive detention. By contrast, the bills filed by Sen. Huffman and Rep. Murr, which reflect approaches more in concert with the Governor's priorities, don't necessarily agree with one another but both reflect a desire to expand detention and to eliminate local options to release defendants pretrial. (There are other bail bills that are better, including one from Rep. Ron Reynolds, but they don't have a prayer while Abbott is Governor.)

Meanwhile, advocates themselves aren't all on the same page. Some think risk assessments are racist harbingers of evil; some think they're fine, or at least inevitable and not worth fighting over. Some want to find a sliver of agreement with the bills moving in order to retain a "seat at the table." Others, and Grits is in this camp, think nothing supportable can pass this year and we should wait for the 5th Circuit to lay the groundwork for what's next.

Essentially, there remain people who believe there's a Venn diagram of bail reform out there that looks like this:

Somewhere, theoretically, they imagine there's a policy no one has found yet that hits the sweet spot and if they just stay at the table long enough, maybe they'll discover it. The problem is, that's not the diagram. The IRL version of bail reform probably looks more like this:

The 5th Circuit cases and reformers are largely engaged in the same project: Reducing pretrial detention for defendants who can't afford bail. It's possible, even likely, that federal courts will choose a route to that goal that's less aggressive than abolishing money bail entirely, as most advocates would prefer. But there's more overlap than distance between the court rulings so far and what #cjreform folks would like to see happen. Certainly the courts are pushing local actors toward bail reform more aggressively than had ever been possible through the political process.

By contrast, Abbott and his legislative enablers are mainly concerned with expanding pretrial detention. Some of their proposals are so radical they'd require amending the Texas Constitution to accomplish. The tiny shreds of overlap between Abbott and the conservative wing of a bipartisan reform movement don't coincide at all with the project the federal courts have undertaken. There was a time several years ago when legislators could have headed off federal litigation by passing bail reform. But they failed to act so the federal judges moved forward and did their jobs. Now that ship has sailed. If the Texas Legislature passes a bill at this point, it will either address issues tangential to the federal litigation or likely be overturned by it in the near future.

In that light, I don't see a sweet spot on bail reform in 2021 that's a) legislatively viable and b) conforms with what are likely to be new federal court mandates arriving in the next 2-3 years. At this point, bail-reform supporters in Texas should just oppose these bills en toto. For the moment, it's a can't-get-there-from-here situation.

.jpg)