Friday, July 30, 2021

Austin PD teaches cadets US Constitution using material from John-Birch-Society shill

Wednesday, July 28, 2021

What if any changes to police deployment patterns might reduce violent crime? Hotspot policing vs. ↑ resources for detectives

There are SO many studies on this topic, many of them very micro-focused and not particularly useful, let me give you a big-picture, 50-year overview of the research findings on this.One of the most robust findings in criminology is that patrol doesn't reduce crime overall or make people feel safer (going back to a major field study in Kansas City in the '70s), and police staffing levels appear to have no relationship either way to crime going up or down.However, this result didn't sit well with police or their advocates, and in the 1980s, criminologists began to revisit the question, this time shrinking both the geographic areas examined and the time periods considered. Finding a negative result wasn't considered a failure of the tactic, just evidence that the geographic and temporal constraints hadn't been sufficiently narrowed. Eventually, they were able to demonstrate that flooding a neighborhood with police to perform stop and frisks and/or pretext stops correlated to reduced reports of serious crime IN THAT GEOGRAPHIC AREA for whatever period of time they kept it up. There are a bunch of studies out there like that.However, few of the hotspot studies I've ever seen claim this is anything more than a short-term effect that goes away as soon as police leave. And most researchers will admit it's likely crime just bleeds into other geographic areas, the way air moves to the sides when you squeeze a balloon.N.b., generally, what you see when these studies are portrayed in the policy arena is a bait and switch. Cops say "hot spot policing works" then use that to call for increased staffing. But we KNOW increased staffing doesn't correlate to greater safety. The hotspot research is about deployment of EXISTING officers, not an argument for hiring more overall.Finally, if I were making public-safety recommendations for Houston based on the current data, I wouldn't be focused on patrol or hotspot policing, but beefing up the detective ranks, maybe even AT THE EXPENSE of patrol. Again: The real issues are how officers are deployed, not how many there are.

There are 200 Narcotics Division detectives at HPD - far more than in homicide. I've argued Narcotics should be entirely disbanded, and those detectives should be moved to investigate 1) homicides and 2) shootings that do NOT result in death. The latter are almost completely ignored but are essentially similar to the murder cases; whether the victim lives or dies has more to do with the EMTs and doctors than the intentions of the shooter. (I'm not generally a fan of the Manhattan Institute, but they recently published a report reaching the same conclusion.)

So that's the redeployment I think we should be pushing for if the goals are to reduce racial disparities (they're TERRIBLE in Narcotics) while reducing violent crime: Expansion of detective resources to investigate non-fatal shootings. That'd do FAR more to improve safety than anyone would ever claim for hotspot policing.

If you ask what police are actually DOING to reduce crime in hotspot areas, criminologists have no answer. It boils down to what I've dubbed the "Scarecrow Theory" of policing: Their mere, occasional presence wards off potential criminals. But cops aren't deployed theoretically, and as a practical matter, what they do while they're there (if they're deployed to a hotspot and not responding to IRL crime reports) are traffic stops and stop-and-frisks of pedestrians. And most of the people with whom they engage are not and never will be shooters; there's a disconnect between the strategy and the desired results.

I don't consider it some radical position to say homicides and non-fatal shootings should be better investigated: Clearance rates for murder in Houston have declined from 89% in 2011 to 49% last year. And "hotspot" policing would do nothing to change that dynamic.

If the problem you want to solve is violent crime, focus on violent crime. Don't engage in generalized harassment in black and brown neighborhoods then assume reduced murders will somehow be a secondary effect.

Tuesday, July 27, 2021

Austin PD's "early warning system" is a failed PR stunt, like pretty much all of them

It's been many years since I've been that deep in the weeds on the topic, but a new Austin city auditor report on their police department's "early intervention system" - known within the department as the "Guidance Advisory Program" (GAP) - confirms my sense that they're essentially worthless. Austin's, the auditor found, "does not effectively identify officers who may need assistance."

As is typical, there has been no local MSM coverage of the audit. (I know, gentle readers, you're shocked at the omission!)

APD's police early-warning system suffers both from over-identification and under-identification. It gathers only three, not-very-probative data points and ignores data used by systems in other cities. The thresholds to trigger review are set too low, so too many officers are identified for intervention and the system has little predictive value. At the same time, many officers meeting thresholds are not identified at all. On use of force (at APD, called "response to resistance), the department failed to identify about a third of officers who should have met the threshold for review. Moreover:

When officers are identified for assistance, the GAP does not connect these officers to existing APD support or wellness services. Also, APD does not track or analyze program trends to evaluate officer or program performance to ensure the GAP is fulfilling its mission. In addition, APD management has not generated true program buy-in and the GAP is not working as intended.

The auditor sampled 60 activations and found supervisors identified no issues 93% of the time, resolved the issue with a conversation 7% of the time, and NEVER created an action plan to correct officer behaviors, even though that's theoretically supposed to be triggered by the system. As a practical matter, they're just not doing anything with the information:

APD staff said there are no performance metrics reported in relation to the GAP and they have no way to measure the program’s success. In addition, the department is not analyzing results to identify trends or determine if certain officers, assignments, or supervisors need additional support services.

Even an officer triggering the system three times in three quarters based on 45 total use of force incidents was found to have displayed no "pattern" that caused concern. Intervention after 45 incidents wouldn't seem particularly "early" to this writer, but if they're not going to review outliers, anyway, IRL it hardly matters.

The reality is, as the auditors wrote, "APD is not creating an environment of trust and transparency" regarding its responses to officer misconduct, either with officers or the public, and failures of the early warning system are a symptom of that broader problem.

That said, none of the other early warning systems in Texas work well, either. There are no real best practices and as a result, their structures are all over the map. Here's a summary from the report of the information gathered in each one, which varies quite widely.

Dallas' last chief Renee Hall proposed spending nearly a million dollars to revamp their system, with no results so far. The one in Houston tracks 10 different metrics, compared to 3 in Austin, but the Mayor's task force on police reform last year found it ineffective and recommended an upgrade (without specifying details).

I suppose it's possible an "early warning" system could be devised that would fulfill the goal of reducing misconduct, but academic reviews have found little evidence for their effectiveness (if plenty of enthusiasm for giving it the ol' college try). Grits believes their popularity stems largely from their PR value: It's something police chiefs can say they're implementing, improving, etc., that will take the heat off them in the near term because they ostensibly need time to launch a new program. The program never seems to work, though, whether they monitor three data points or 10. Then another scandal happens and suddenly we're revamping the early-warning system again.

Austin doesn't need APD to waste time on this pointless paper shuffling and IMO they should scrap it. If managers want a list of officers who need retraining or intervention, they should ask Farah Muscadin, the head of the Office of Police Oversight, for a list. She knows perfectly well who the problem officers are at this point, even if APD brass isn't paying attention.

Thursday, July 22, 2021

Murders in Texas increased 37% statewide in 2020, with Republican-led communities suffering the biggest spikes. But overdose deaths doubled murders. Are we focused on the wrong problems?

By contrast, DPS reported 1,403 homicides statewide in 2019, and 1,927 in 2020. While that's a big increase - 37% statewide, and not at all concentrated in Austin and Houston, as the Governor would have you believe - it still means overdose deaths are killing far more Texans than murderers.

Republicans are pointing to the murder spike to call for massive increases in police spending and regressive changes to the state's bail system, even though there's no evidence that higher police department budgets or limits on charitable bail organizations will stop these murders (Abbott's pet projects).

By contrast, there are proven policies that reduce drug overdose deaths. One is reminded at this point that Gov. Abbott in 2015 vetoed Good Samaritan legislation that would have let people who call 911 when someone overdoses on illegal drugs avoid criminal charges. The following year, 1,257 Texans died from overdoses; since then the number has ballooned to more than 4,000! Local programs launched and funded last year in Austin were aimed directly at reducing overdose deaths, sending paramedics instead of police to respond. (Then-Chief Manley had insisted his officers would not administer naloxone to overdose victims, declaring EMS should play that role.) But before we could see the results, Abbott pushed through a law to punish Austin for its public-safety budget choices. Apparently, some dead sons and daughters are more important to the governor than others.

And what Abbott thinks, regrettably, has a lot more to do with what the MSM deems "news" than the relative death counts. While Seline's story is the first we're hearing of last year's overdose death increase, how many stories have we seen on the murder spike in this or that city, usually based only on a partial year's worth of data, and WITHOUT acknowledging the statewide numbers?

Before this blog post, I've been unable to find anyone reporting Texas' 2020 statewide murder totals in the press: Google the topic and nearly all the stories involve city-level analyses, at most. (To be fair, the statewide "Crime in Texas" report from DPS for 2020 hasn't been published yet; I found the 1,927 number in a DPS report on border crime.)

No matter how you slice it, the statewide murder increase last year was far too big to attribute to Democrat-led cities alone. Even Houston, which saw its murder total spike by more than 100, can't explain more than a fraction of the increase. Like overdoses, this was something that happened everywhere in the state. It would not be unreasonable, in fact, for voters think the governor should be held to account for that. But that hasn't happened because skewed press coverage handed Abbott a megaphone to attack his enemies instead of vetting his claims. To their credit, the Texas Tribune pushed back on this meme, and now, finally, a few outlets are joining in. But the damage has been done.

Some days I think the media beating the drums about homicides while downplaying or ignoring much greater public health/safety risks reveals a partisan agenda; others, I think it's an economic one. Texas' lapdog press may be mostly content to recycle misleading and politicized crime headlines because the MSM's business model has been built on sensationalizing crime for more than a century.

But this year, in this election cycle, there's a new level of hyperbole. Governor Abbott and his local acolytes want to blame leaders in Austin for murder increases, but the capital city, with more than a million people living here, had just 19 more murders in 2020 than it did the year before. That's tragic, but by comparison, Texas saw murders increase statewide by 524 last year on the Governor's watch, and Republican-led cities like Fort Worth and Lubbock saw much bigger percentage increases than Austin (e.g.: murders increased 60% in Fort Worth, whose population is slightly smaller than Austin's, from 70 to 112; in Lubbock, which is a quarter of Austin's size, murders spiked 105%, from 20 to 41.)

You'd almost think the demagoguery about Austin was a smokescreen so no one would ask about murder increases statewide under Republican leadership, much less overdose deaths and how much Abbott's policies (and veto) contributed to them.

In reality, murder and overdose deaths - which increased in both Democratic and Republican-controlled cities and counties - appear to be things which are IRL unaffected by your party of choice. They aren't partisan problems, they don't lend themselves to partisan solutions, and when the media and government leaders insist on considering them through a partisan frame, it makes the situation much more stupid and untenable.

Monday, July 19, 2021

Arguments for Republican bail bill become nonsensical when debating rural jails

Saturday, July 10, 2021

Rural counties hurt worst by politicizing bail policy: My testimony against Texas' bail bill

Today your correspondent testified against HB 2 - the Governor's bill attacking judicial discretion in bail setting - in the House Select Constitutional Violations and Remedies Committee, but in 3 minutes couldn't get through it all. So lets post my (mostly prepared) remarks here.

_______________

Good morning Mr. Chair, Madame Vice Chair, and esteemed committee members,

The bill before you as written is bad for Texas.

This is true for many reasons, some of which will or have been raised by others. But I want to talk about how it will boost local jail incarceration rates and put additional upward pressure on property taxes with no particular benefit to public safety, but with many identifiable harms.

As I speak to you today, according to the Commission on Jail Standards, 93 Texas counties are paying to house prisoners outside their county jails to avoid exceeding state overcrowding standards. Nearly all of these are rural and border counties.

A few years ago, the big overcrowding problems were happening in the large counties, and many of you will remember when Harris County was farming out inmates in Louisiana and several of its neighboring counties. Now, the big counties mostly have those problems under control and it’s rural counties feeling the squeeze. And after 2019, they must face these challenges with new limits on property tax revenue.

This legislation will harm counties by increasing pretrial incarceration in cases where judges previously recommended release. For those 93 counties and maybe even more in the wake of this legislation, it will mean more prisoners housed outside the jail for which counties must pay per-diem contract rates.

It’s not some scary thing that judges have discretion to release defendants on bail. They had it when crime was going up in the ‘70s and ‘80s, but also when it was going down for 30 years beginning in the ‘90s. That it’s ticked back upward - nationally, it should be emphasized, not just in Houston where they’ve had judicially-mandated bail reform - is no reason to change such a fundamental part of the justice system on the fly.

This bill is completely different from the bills we saw in the regular session. It doesn’t feel like there’s a plan so much as a political agenda, and that never leads to good outcomes in the justice system.

While I’m here I wanted to refer this committee, if you haven’t read it yet, to the Houston Chronicle coverage of the bail system there which you’ve already heard about today. Despite the hair-on-fire quotes from Andy Kahan and the police unions, if you look at the numbers, for a city as large and diverse and Houston, they were really rather modest.

So much of this bill is about limiting personal bonds, but when the Chronicle looked at data since 2013, only 2 people out on personal bonds had been accused of violent crimes.

About 376,000 people were released on bond over this period. 79 went on to kill someone while out on multiple bonds, or 0.02 percent; only 0.01 percent, or, 38 alleged killers, had received multiple felony bonds over the eight years the Chronicle looked at, or an average of just less than 5 per year. In a city of 2.3 million, with a justice system as vast as Houston’s, these are tiny numbers.

The Chronicle and Andy Kahan made much of recent increases in the murder rate, but individual anecdotes aside, statistically those were much larger increases driven mostly by murderers who WEREN’T out on bond.

The Chronicle found that 7 percent of murders during the period they studied involved people out on bail. But that means the overwhelming majority, 93 percent, were committed by people who hadn’t been released on bail.

If you do this, it’s not going to do squat to reduce Houston’s murder problem and none of you should pretend it will. Lubbock and Fort Worth saw bigger murder spikes, percentage-wise, and they haven’t undergone bail reform at all. This an effort to politicize the justice system and I believe y’all should oppose it.

Thank you for your time.

Sunday, June 20, 2021

Abbott vetoes demonstrate continued antipathy toward #cjreform, bootlicking toward police unions

By contrast, most of the big stuff never made it to the governor, and here's how Kathy described the reform bills Abbott vetoed:

The Governor's vetoes are a final punch in the nose for the bipartisan criminal justice reform movement, and a clear reminder (in case we forgot for a second) that the 87th from start to finish has been mainly about Abbott's re-election on a platform of "tuff" on the poorest and most desperate among us.Abbott vetoed SB 237, predictably, after announcing that he was clearing out a prison to hold migrants arrested for trespassing by his promised army of troopers. That bill would have added criminal trespass to the list of Class B offenses for which an officer could (discretion only) issue a citation instead of arresting.Abbott vetoed HB 686, juvenile "second look" after even Dan Patrick found a version he could live with. The final bill allowed a person who committed a violent offense as a kid to get a review and possible release (just the possibility, that's it) after serving at least 30 years. Hardly soft on crime, and a bill supported by the Catholic Conference of Bishops, TPPF, Goodwill, United Way and a host of others. Who opposed? Only Ray Hunt on behalf of the Houston Police Association. Hmmmm....Abbott vetoed HB 1240, a bill with no formal opposition at all. That bill would have authorized fire inspectors to issue citations over fire code violations the way health inspectors do. Apparently now, you have to be a sworn police officer. A bill that would have empowered other public safety agencies to make the public safer without having to use police....Hmmmmm....Abbott vetoed SB 281 that would have finally ended a police investigative technique from the 70s and 80s called forensic hypnosis. Which is pretty much what it sounds like. A "specially trained" police officer applies hypnosis to a witness or suspect and elicits, well mostly garbage. Because...hypnosis.Finally, and this is the one that, for me, shows Abbott's hand. He vetoed HB 787 that would have allowed formerly incarcerated people and people on probation to get together (without violating terms of probation against fraternizing with criminals) for purposes of "(1) working with community members to address criminal justice issues; (2) offering training and programs to assist formerly incarcerated persons; and (3) advocating for criminal justice reform, including by engaging with state and local policy makers."It appears that the voices of the formerly incarcerated were very effective this session, so we can't have any more of that.I could not find any veto messages for these bills posted yet, just the fact of the veto listed on the Capitol website. So if the Governor has anything useful to say for himself, I'll add more later. For now, these vetoes kind of speak for themselves.

Monday, June 14, 2021

Travis County jail expansion makes no sense, so of course they might do it anyway

The issue is construction of a new women's jail, a proposal originating in the county's 2016 strategic plan. The county will vote tomorrow on whether to spend $4.3 million to plan construction for a proposed $80 million women's jail expansion, though high construction prices due to recent commodity price spikes make it likely the costs would be higher.

But a lot has happened since 2016, most notably that the jail population has plummeted, starting before COVID then accelerating over the last year. County Judge Andy Brown and Commissioner Ann Howard have proposed a resolution to reevaluate the 2016 plan in light of current needs.

At this point, the jail is less than half full. Among women, most of them remain in the jail less than three days. Of the current population, only about 40 women have been incarcerated longer than that.

Spending $80 million on facilities that will mostly benefit so few women makes no sense. Yes, it's true bond money can only be spent on facilities. But bond PAYMENTS come from the same tax revenues that fund every other part of the budget. The idea that this investment doesn't compete with resources for services simply doesn't hold water and apologists for the new jail should stop saying it. We all know where the money to make debt payments comes from!

Even more disingenuous are those who raise the "murder spike" to argue for expanded jail space. Most murder suspects aren't women, and most people in jail aren't murderers. Anyway, the new facilities wouldn't be ready for four years! Short-term crime trends aren't an argument for long-term capital investments, especially when there's so much vacant jail space to begin with.

All sorts of factors have contributed to Travis County's jail population reduction and make it likely it will be sustained. Judges who began using more expansive pretrial release protocols to save lives during COVID say they largely intend to continue them once COVID abates. The county has largely ceased prosecuting marijuana cases, and many other nonviolent misdemeanors and low-level felonies are being handled through front-end, pretrial diversion. A new public defender's office is just getting set up but will soon provide more defendants better representation, making pretrial release more likely.

At a minimum, the jail population reduction in the five years since the 2016 plan provided breathing room for the county to reevaluate. Back then, the jail already had more people in it than it does today and lumber prices weren't through the roof. There's simply no need to build more jail space now and from a cost perspective, it's a bad moment to do so. Let the overheated lumber markets die down and give the system time to see if the reductions will be sustained. There's no immediate pressure to do otherwise.

In many ways, this is a bizarre debate. Usually, when Grits argues against new jail spending, jails are full and I'm suggesting diversion programs and cohorts of arrestees who can be safely released as an alternative to jail expansion. But in this case, Travis County faces none of those pressures.

Commissioners Shea and Travillion want to build a jail because the Sheriff wants it, not because the county needs one. But there's a reason the Texas constitution separates jail management functions from budget writing: It's the commissioners' job to vet such proposals, and any rational analysis of county needs argues against jail building right now.

We live in such an odd political moment. Jails are so expensive and cumbersome for counties, usually commissioners only want to build them as a last resort. To have self-avowed liberals wanting to build one when they don't need the space feels like a bit of a through-the-looking-glass moment. But for long-time observers, perhaps it isn't as surprising as it seems.

Liberals pushing to build a jail we don't need feels to me like a throwback to the Ann Richards era. Then, liberals championed prison building as a last ditch effort to stop the state from flipping to Republican control. Trying to "out incarcerate" Republicans didn't work then and it won't help today. Instead, it will dissuade voters Democrats need from coming to the polls at all.

Jail opponents have presented the County with a robust set of alternatives that address Travis County's real needs -- build mental health crisis centers and intermediate treatment options, housing, substance abuse services and more. People like those ideas. They poll well. They actually work. Why not stop trying to out-Republican the Republicans and stand for something different?

UPDATE: After a fairly dramatic hearing in which three commissioners for a time appeared to lean toward moving forward, more than 100 speakers against from all walks of community life convinced them to delay the jail project for a year in a unanimous vote. This got uglier and weirder than it needed to be. Unless it was contractor-driven, I still don't understand the urgency behind jail proponents' push while the jail is half full. Glad they delayed it.

Thursday, June 10, 2021

Expungements for old weapons charges under Texas' new unlicensed-carry law could be widespread, but likely initially limited

Even so, this is the most common weapons-related offense. In 2018, more than 13,000 Texans were arrested for UCW or some other weapons charge - about 48.3 weapons arrests for every 100,000 people.

Projecting backward, hundreds of thousands of people have likely been arrested for unlawfully carrying a weapon over the years, and now all those cases can be expunged.

Will they? That's another question. It's not automatic. People must file an ex parte petition with a district court to have their old conviction reviewed for possible expungement. So they'll need to hire a lawyer or possess the gumption to strike out on their own to tackle the job. Some will; most won't.

I'd love to see some advocacy group create a form ex parte petitioners could use to ask the court to expunge their old cases. (Hey, Texas Fair Defense Project and/or Civil Rights Corps, y'all up for this?) Prosecutors have historically fought expungement petitions - particularly on weapons charges - because they want to be able to use people's past crimes to seek enhancements or argue for harsher sentencing. But they don't have much grounds to oppose expungement in these cases; the law is pretty clear.

In the long, run, though, if legislators think these old convictions should be expunged, they should instruct it be done as a class. This provision will help a few folks but will mostly remain a symbolic gesture unless lawyers are paid to process the cases or expungement is made automatic.

Thursday, June 03, 2021

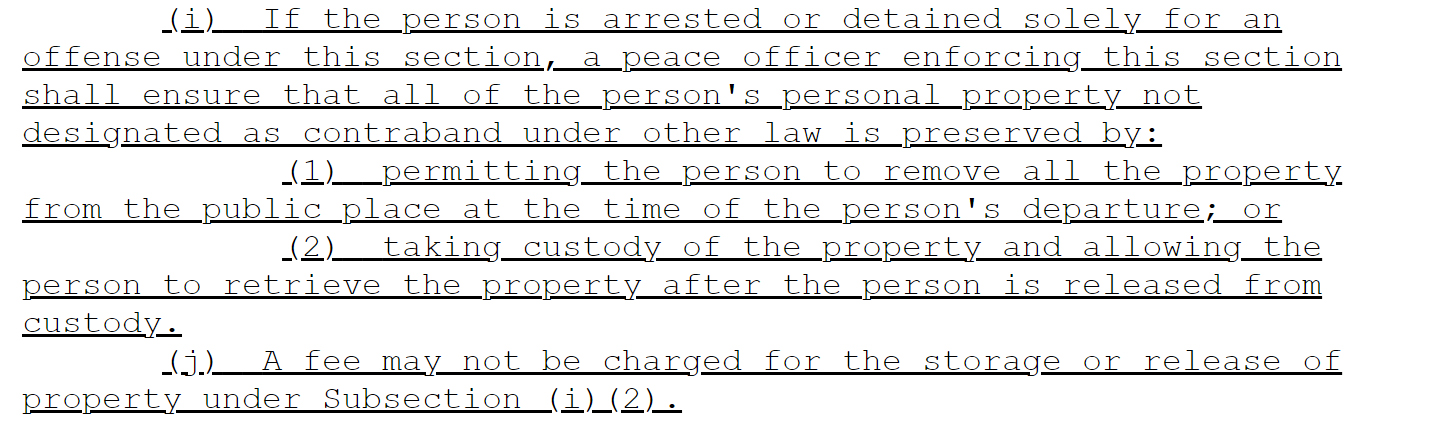

New TX homeless ban creates unfunded mandates for cities: Costs downplayed during #txlege process but cities must foot bill to store homeless belongings and can't limit arrests to ↓ costs

Regardless, the bill forbids cities from establishing policies that limit these arrests, so if and when costs start racking up, the Lege will have taken away their ability to limit this expense.

Thursday, May 27, 2021

Fascism Unsheathed: Let's be very clear about what just happened at the #txlege

In 2021, the spear tip was unsheathed and thrust deep into the body politic: A combination of the pandemic, President Trump's defeat, and the January 6th insurrection seem to have finally awakened the beast. This was the year the far-right wing of the party finally got its wish list they'd been denied in the 20 years since Republicans took power in Texas: The entire legislative session was about abortion, guns, jingoism, and "backing the blue." Compassionate conservatism and non-gun-themed libertarianism were more or less banned from the building, or at least the eastern wing.

The Texas House, with a larger, more ideologically diverse membership, retains a broader array of Republicans that still includes some "small government" and/or "compassionate" types. They managed to pass several significant criminal justice reform bills, but virtually nothing of consequence made it through the senate. Reforms with overwhelmingly positive, bipartisan polling numbers like reducing marijuana penalties and ending arrest/jail for Class C non-jailable traffic offenses could never even get committee hearings on the eastern side of the building. Instead Sen. Joan Huffman wasted weeks on a failed effort to gerrymander appellate courts to rescind recent Democratic gains.

Some of this lurch toward totalitarianism was overt and ham-handed, perhaps most notably legislation to require sports teams to play the Star Spangled Banner. More insidious were attempts to control historical narratives about race and slavery in Texas schools and museums. These efforts were as shameful as they were transparently authoritarian. We're just a step or two away from parading historians through the streets in dunce caps.

Perhaps the most subtly fascist influence radiating out of this session was HB 1900, ostensibly punishing cities that "defund police." Large cities and counties henceforth must prioritize spending on law enforcement, leaving roads, parks, social services, or any other traditional municipal functions to wither in a time of massive urban growth.

Grits believes the purpose here is both political and dystopian: Texas' large cities are now almost all (but Fort Worth) run by Democrats. So the Governor and his allies aim to make cities un-manageable, then blame Democrats for mismanaging them. Given the state's largely lapdog political press, I understand why he thinks he'll be able to control that narrative and redirect blame. He's probably right.

It's a valid and effective political strategy, even if it's nonsensical bordering on asinine as public policy.*

If HB 1900 is enforced, it will be incredibly harmful: All large Texas cities have for years already prioritized police spending over other municipal functions which have languished and at this point require investment this bill will prevent.

Now, new spending must go first to the cops, and with municipal revenue caps installed last session, that pretty much precludes spending on anything else. This exacerbates the problem of which police chiefs have complained for years: that they're being tasked to solve social problems for which they're ill equipped. Nowhere is that dynamic more clear than in the statewide homeless ban, which criminalizes cooking or sleeping outside under a blanket. Poor people evicted from their homes? Send police. Mental illness untreated? Send police. Veterans with addiction and/or PTSD who can't hold a job and end up on the streets? Send police. Elderly people forced to live in tents because inadequate social security checks won't cover escalating rents? Send police. I can't think of a clearer definition of authoritarianism.

Not only does the legislation criminalize poverty and punish it with unreasonable penalties (fining homeless people is a fool's errand and jailing them for sleeping accomplishes nothing), it begins the process of de-linking law enforcement from civilian control. HB 1925 prevents cities from setting policies for police departments' enforcement priorities regarding homelessness, making them over time both ever-more extravagantly funded (thanks to HB 1900) and increasingly unaccountable to the cities paying their bills.

Who knows how far we'll head down that path? But history generally views with disapprobation those periods when the armed agents of the state are left free to abandon the public weal and act in their own interests. The Roman legions, for example, were prone to deposing emperors who asked them to pound swords into ploughshares. Law enforcement interests in Texas behave the same way, which is why Emperor Abbott panders to them so incessantly.

Grits see this as a camel's nose under the tent, mandating cities fund police departments to the exclusion of other priorities while eviscerating cities' policy-setting role and leaving the cops as independent actors. Well-funded, unaccountable law enforcement acting as independent agents outside of civilian control is the sort of situation that makes me use a harsh term like "fascist." The net sum of all these policies taken together aims Texas' largest jurisdictions squarely in that direction.

Indeed, this year it became evident that police reform of even the smallest sort cannot occur in Texas while Greg Abbott and Dan Patrick remain in office. Both of them defer almost completely to police-union interests on criminal-justice policy. Even the "Sunset" bill for the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement could not pass. Legislators wanted to create a "blue-ribbon commission" to study reforming the police licensing agency, but police unions don't want reforms proposed and so killed the bill outright.

Of roughly eight different bills making up the Texas George Floyd Act package, only one (banning chokeholds) made it through in anything close to the original, filed version. Another, the "duties" to intervene and render aid, passed in a form that will almost certainly guarantee no interventions and very little aid.

Two years ago, I wrote that 2019 was a "killing field" for criminal-justice reform bills; this year was worse. This time, law enforcement wasn't just killing off reform proposals, they were ascendant, insisting their interests be prioritized above all other public-policy goals or community values. And Texas state leadership all but fell over themselves giving them everything they wanted.

This blog and Just Liberty, the group I work for, focus a lot on wonky minutiae in order to identify narrow reforms both parties can support. But we can't wonk our way out of this political moment: What's at stake is nothing less than the soul of the state and arguably, given national implications of Texas' role in the GOP and the electoral college, the future of the American political experiment.

Texans of good will: Today, you're living through the American equivalent of the Weimar Republic and history has placed us at the epicenter of far-right-wing ascendance in American politics. Behave accordingly. We may not get another chance.

*More than asinine, to channel Stephen A. Smith, this is assi-ten, ass-eleven ...

Friday, May 21, 2021

On the Myth of Prison Closures Generating Cost Savings: How TDCJ can ↓ prisoners by 20% and still see costs rise nine figures per biennium

Bills that increase incarceration are deemed to have no significant cost, even though every additional prisoner requires supervision, food, healthcare, etc.. And bills that decrease incarceration weren't deemed to generate budget reductions on the grounds that no real money was saved unless the state closed prison units and could save money on guard salaries.

So, for years, bills increasing incarceration were treated in the state budget as freebies while bills reducing incarceration received no credit from budget writers.

Then, in 2013, Texas finally broke through and reduced incarceration enough to begin closing units. Since that time we've closed about a dozen of them. And yet, every session, TDCJ's budget goes up and up.

It turned out to be a myth that closing prison units would reduce the budget. Frankly, your correspondent is as surprised as anyone, though with 20/20 hindsight it's easy to see why.

Texas has reduced its prison population by about 20 percent, but most of that reduction has come among prisoners with shorter sentences. Meanwhile, the big cost drivers at TDCJ are 1) healthcare for elderly prisoners and 2) deferred maintenance on old units.

So, even with the lowest prisoner population in the 21st century and a dozen units shuttered, TDCJ's latest budget includes huge, nine-figure increases:

That said, this is a surmountable problem using mechanisms available under current law. With the exception of those with LWOP sentences (who're mostly not elderly yet, anyway, though they'll contribute to the problem soon enough), some 60 percent of TDCJ prisoners are eligible to be paroled immediately. Indeed, some 15,000 of them have already been approved for release but remain incarcerated because TDCJ only provides treatment services post-approval. Legislation to move the treatment timeline up passed the Texas House but the Lt. Governor as of this writing has refused to refer the bill to committee.

So for the time being, expect Texas prison costs to keep ballooning: Looking at the bills still moving in the waning days of the 87th Legislature, the state doesn't appear poised to change any of the dynamics causing it.

Monday, May 17, 2021

Might "anti-defund" legislation demilitarize and redefine 21st century policing? On the predictable if unintended consequences of micromanaging city budget decisions

On its face, this would bind Texas cities' hands and make them all but unmanageable. After all, the biggest problems they face stem from the fact that their predecessors over-invested in police, jails, and prisons to confront social problems instead of investing in other solutions (e.g., mass transit, mental-health-and-addiction services, transitional housing and services for the homeless).

I believe that's the goal: A feature, not a bug. Governor Abbott intends to make Texas cities unmanageable and then blame Democrats for mismanaging them. If Republicans ever regained control of these jurisdictions, his office would cease to enforce the "defund" strictures (it's 100% at his discretion), and I wouldn't expect these requirements to ever be imposed on Republican-led cities, even though several of them in recent years have reduced their police-department budgets.

But for large cities which for the foreseeable future are governed by Democrats, this creates a conundrum. Big-city police chiefs have been complaining for the past decade that their officers are being asked to impose criminal-justice solutions to what are essentially social and healthcare problems they're ill-equipped to handle. Now, though, the Legislature is poised to insist cities can only confront these problems with police: A full-blown Catch 22 from a management perspective. They're leaving cities with no good options to address urban problems, which again, Grits believes is the point.

That said, I also believe this ham-handed attempt to bludgeon city leaders underestimates the variety of tools at their disposal and the wide array of methods available for cities to get around any strictures.

I'm sure there are many options, but here's my first thought: If the anti-defund bill passes, cities should begin to deploy unarmed officer cohorts whose primary functions fulfill the needs they'd otherwise fund in other parts of the budget.

Anyone who's traveled to the UK has seen unarmed police officers ably enforcing the laws as surely as American cops do with guns, and when they're needed there are special armed squads which can be called out or beat officers can be armed in a pinch.

Here, though, Grits suspects squads of unarmed officers might be deployed much differently. For example, using money diverted from the police budget, Austin has begun having EMS respond to certain mental-health calls, with impressive early successes. If they're not allowed to expand that going forward because money must be spent on police, that won't obviate the need for non-carceral solutions to untreated mental illness.

So what should they do? No one but fools think Texas can arrest its way out of these problems. And once legislators go home (without having expanded Medicaid, I should add, which might pay for non-carceral mental-health treatment), cities will still have to confront these issues with whatever tools are left in their toolbox.

Consider the possibilities of unarmed social-or-health workers with a badge but no gun responding to homeless and mental health calls, possibly working closely with or even for the expanded EMS cohort recently created for mental-health first response and various city service providers. Whereas past protocols put officers in charge when they were on site with EMS, those roles could just as easily be reversed, particularly for the squad of unarmed officers whose primary role isn't arrest-and-incarcerate.

Such a program could include specialized recruitment and training to get people with relevant backgrounds in health care or social services who want to, say, work with the homeless or the mentally ill but don't want to carry a gun, enforce traffic laws, fire bean-bag rounds at protesters, etc..

These unarmed officers could always call their armed colleagues if needed but would primarily be deployed at tasks where it's not. Over time, cities could identify other activities where unarmed officers could fill roles that, in a more rationally governed state, might not normally be associated with law enforcement. But if cities are only allowed to fund cops, don't be surprised if the definition of "cop" inevitably expands.

The governor and his allies intend to box cities in, but I suspect they're making a strategic error. There's a bit of common military advice dating to Sun Tzu: Never completely surround an enemy's army; surround them on three sides and leave open the path you want them to take. The "defund" legislation does the opposite, attempting to surround cities completely and give them no path at all to move forward. Sun Tzu counseled that this could lead to either a) desperation and a bloodbath or b) creative tactics by the enemy that exploit one's army's overreach.

The latter is where I think this is headed: The Legislature meets only once every two years while city councils meet all the time and deploy vast bureaucracies to find ways to bypass legal barriers erected at the capitol. There will be several obvious workarounds, but here's a starting point: If the "punish defunders" legislation passes, Grits believes it will mark the beginning of a transformation of the definition of "police officer" as cities deploy services under the policing banner to confront problems they're not allowed to pay for in other parts of the budget.

If cities can only spend money on cops but the problems they must confront are only tangentially crime-related, inevitably they will begin to adjust what police do to deploy the only resources at their disposal at the biggest problems facing their constituents.

If I'm right, the "defund" legislation could have an unintended consequence of rapidly altering the definition of what it means to be a "police officer" in this state. How ironic would it be if this train wreck of a policy, promoted in the name of defending law enforcement, ends up being the trigger that launches its devolution into a less militarized, more service-focused 21st-century institution?

That outcome's not inevitable - the police unions would fight it, just as the Roman legions resisted pounding their swords into ploughshares - but Grits wouldn't be surprised: As the prophets foretold: The arc of history is long, but bends toward justice.

Monday, May 10, 2021

Austin PD failed to define 'resistance' that justifies use of force, made up 'unique' category of force vs. suspects who're 'fixing to' resist

But unlike other agencies that use a "response to resistance" model, the Austin Police Department's General Orders do not define "resistance," much less outline what force may be used by officers in response.

Instead, resistance is used as a catch all and defined as anything that would justify use of force by a "reasonable" officer. This is language from a US Supreme Court case, Graham v. Connor.

Grits should mention here: I've been reading technical, bureaucratic, legal, and academic writing on police use-of-force issues for about 25 years. Part One of this memo vis a vis response to resistance, providing both legal and conceptual frameworks for understanding the issue, may be the single most clear, cogent, well-written discussion of the topic I've ever seen. Good job, Farah Muscadin!

She outlines how American police department policies broadly regulate police use of force in one of two ways: the "just be reasonable" approach or the "continuum" approach. The DRRM purports to employ a continuum and APD touts the various resistance categories frequently in its rhetoric surrounding use of force. But Muscadin revealed that the actual APD General Orders do not employ a use-of-force continuum. Instead, they merely say officers' actions will be judged based on whether they're "reasonable," but give no guidance as to details.

Muscadin recommended defining "resistance" and detailing a use-of-force continuum similar to other departments which have adopted the DRRM.

Perhaps most remarkably, though, Muscadin revealed that Austin PD has created an additional type of "resistance" - "preparatory resistance" - which appears to be unique among US policing agencies.

Most agencies that use DRRM use four categories of resistance: Passive, Defensive, Active, and Aggressive. Some use different language, but the concept is the same: Passive resistance is being non-responsive; defensive is trying to get away; active is engaging in combat with the officer; aggressive are situations putting life and limb at risk.

The threshold between when it's acceptable to use force against a suspect more or less falls between "passive" and "defensive."

But Austin has inserted a fifth category between those two: "Preparatory resistance," defined as when the suspect is "preparing to" offer greater resistance but hasn't yet. (Think of it as "fixing-to" resistance, as in, "the suspect was fixing to resist, so I tazed him.") The OPO reviewed 15 other agencies' use of force policies, including nine that used DRRM, plus state of Texas standards and the original research on which the approach is based, and Austin's use of this "preparatory resistance" category appears to be both "unique" and unjustified. Muscadin recommended getting rid of it entirely.

This analysis raises two, immediate questions: First, will the City launch a community-driven process, as Muscadin suggested, to "finalize definitions" for various "resistance" categories and to debate the appropriate police responses and policies for each? It's been nearly a month since her report came out and we haven't heard a peep from city or police officials about it. They've all been too busy pushing to relaunch the police academy.

Which brings us to the second issue: If APD hasn't even defined "resistance" in their "response to resistance" policy, and it turns out the policy is a hodge podge that makes up terminology and conflates differing approaches to police use of force standards, is the agency really ready to begin training on it three weeks from now? What do they train on if they haven't even defined "resistance"? When do they tell officers to respond with force?

I don't know. I'm pretty sure they don't know. (Before Muscadin's report, nobody was raising these issues.) But it's another reason to think the city was premature to relaunch the police academy without finishing the publicly accountable makeover reformers were promised last year.

Sunday, May 09, 2021

A #cjreform update for 'The Devil's Dictionary'

Friday, May 07, 2021

Five Observations and a Prediction: Why police budget hikes could become a thing of the past in Texas if HB 1900 becomes law

#1: Policy fights now head to the courts

Every policy fight can and frequently does play out in an array of venues and the legislative process is only one of them. Some of the legislative losses this week are on topics - more restrictive detention policies from bail reform, limiting prosecutor discretion on new anti-homeless laws and arrested protesters, dictating home-rule-cities' budget prerogatives, etc. - that Grits expects to be litigated as soon as they're implemented. Some of it will stand, some of it won't. ¿Quien sabe? E.g., Austin changed its homeless arrest policy after federal court rulings deemed similar laws in California unconstitutional. Once it's changed back, those precedents will now be litigated here. Hell, if it's extended statewide, litigants can cherry pick which judge they want to bring it before. Right now, debates at the Texas Legislature on everything from bail to homelessness to abortion have become rather unhinged from and not particularly cognizant of nor in any way aligned with federal court rulings governing the same topics. Sign of the times, I guess: Picking needless fights on every front. I can't always tell if it's intentional or they just don't know any better. Little of both, probably.

#2: Ex Post Facto: Know the term

The "defund the police" legislation which will likely pass the Texas House today is a rather blatant example of an "ex post facto law" banned in Art. 1, Sec. 16 of the Texas Constitution and Art. 1, Sections 9 and 10 of the US Constitution. House Parliamentarians don't rule on constitutional issues (with few exceptions, they stick to interpreting the House rules), but IRL, courts do. And the originalist history of the ban on "ex post facto laws" is well established: While more commonly used today in terms of criminal law, it was created so that governments couldn't arbitrarily invalidate budgeting and spending decisions.

Thursday, May 06, 2021

Academy relaunch premature until Austin PD eschews hazing culture

We've now seen numerous unflattering assessments of the academy, but none more damning than the report from Kroll and Associates. They found the academy uses a "predominantly paramilitary model," has been "reluctant to incorporate a lot of community/civilian input," and remains "distrustful of non-police personnel."

Notably, a majority of both APD brass and the Academy leadership told consultants they don't agree with critiques of paramilitary approaches to policing and don't intend to change: "APD leadership has expressed its belief to Kroll that a paramilitary structure is an essential component of police culture." wrote the consultants. They want to continue group punishments and "stress-based" techniques (this is a cop euphemism for screaming at cadets.)

So APD brass fundamentally disagrees with and is bucking the new direction City Council wants to go, but we're being told "trust us" and asked to move forward, anyway. Honestly, they must think we're suckers: Don't piss on my shoes and tell me it's raining.

The biggest concern with launching the academy now is that past pedagogical approaches were abusive toward cadets and drove out qualified candidates who chose not to endure these methods. Grits has written about the department's:

strange obsession with perpetuating a culture of hazing and brutality toward cadets, despite evidence this approach drives away women and black people.When these audits were commissioned, the Mayor and City Council promised there would be a collaborative, community process to develop a new curriculum. But on a Zoom call my wife attended last night, advocates invited to the first meeting of that process - the night before the vote to reopen - were given no curriculum to review and told the list of course topics hadn't yet been finalized. In other words, they're just getting started and have barely checked in with community folks, much less secured their buy in.

Perhaps most telling to this observer, Kroll criticized APD's use of a "Fight Day" at the beginning of the academy, in which martial-arts instructors beat up cadets in a boxing ring before they've received any self defense training. After public criticisms, "Fight Day" was relabeled "Will to Win," but it's still the same program. Exit interviews indicate this practice significantly harms retention rates in particular for women and black men.

The reason given for Fight Day is that if officers are assaulted on the job, they should have experienced being in a fight before to know what to expect. But when Kroll asked why it couldn't be done at the end of the academy, after cadets had been trained in self-defense techniques, "APD personnel were unable to provide a persuasive rationale."

Your correspondent believes it's because they prefer to fight defenseless cadets instead of trained ones. The purpose is hazing, not training. Kroll's questions exposed a culture of bullying and hazing that can't be defended on pedagogical grounds.

.jpg)