Here are a few odds and ends that merit Grits readers' attention:

Lawsuit seeking Hep C treatment could come with BIG pricetag

More than 18,000 Texas prison inmates have been diagnosed with Hepatitis C - almost certainly an undercount since TDCJ does not do comprehensive testing - but only a tiny handful receive treatment. The

Houston Chronicle reported on a new federal lawsuit demanding they receive treatment, which could cost up to $63,000 per person. See

prior Grits

coverage and

video of testimony from 2014 regarding Hep C treatment in TDCJ.

Conservative think tank takes on police unions

In a significant development, the conservative Texas Public Policy Foundation

published a new report criticizing police unions for undermining police accountability reforms. In Texas, conservative politicians in the 21st century have largely kowtowed to these groups. Maybe the state's leading conservative think tank can convince them that's a bad approach. In related news, in St. Louis, prosecutors voted last December to join the local police union in response to the election of a new, reform-minded DA. This

academic article makes the case that "This complete and public union of prosecutorial and police interests represents a collapse not only of prosecutorial ethical standards, but also a very real threat against democratically elected prosecutors who would seek to enact the reforms that their constituents desire."

Deep data dive for Big D and H-Town

The project by the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition and January Advisors to publish "data dashboards" for Harris and Dallas Counties' arrest, dismissal, and conviction information allows for important analyses that have never been possible before from publicly available data. They just

published this overview of the project, which includes links to the dashboards and a description of what's there.

Handful of police-officer indictments in Dallas stand out

The Dallas DA's office has indicted four police officers for murder in three years, with two of them convicted. The trial for another, Amber Guyger, begins Monday. Notably, the indictments came under both Republican and Democratic District Attorneys. The

Dallas News has a story describing how rare this is at other agencies. Even in Dallas, only one officer was indicted this year out of 50 (!) officer involved shootings taken to grand juries. Despite the rarity of such developments, the head of the local police union was quoted saying the indictments were evidence of anti-police bias.

DPS out of Dallas, with mixed reviews

The Department of Public Safety has

ended its deployment in Dallas launched by the governor earlier this year. According to an

item from the Houston Chronicle's Austin bureau, "The influx of state troopers drew criticism from some residents and a city councilman, who called for the operation’s end after hearing complaints that enforcement was unfairly targeting people of color, The

Dallas Morning News reported. In August, two troopers fatally shot a Dallas man who the agency said

pulled a handgun after a traffic stop, the News reported." Despite these criticisms, DPS Col. Steve McCraw declared the operation a success, declaring "Certainly there's been some that don't appreciate it, usually the ones that are arrested or have relatives arrested, and we understand that." That seems like an odd assertion when one of the most vocal critics is a city council member.

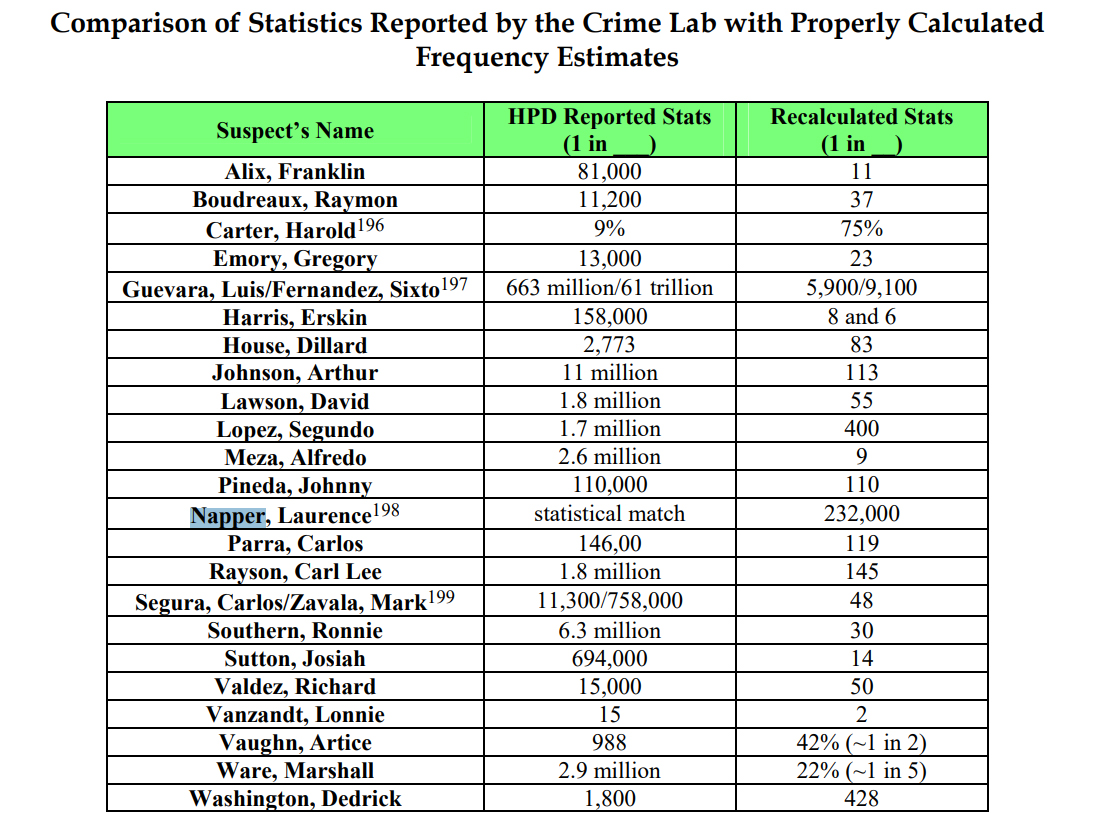

DNA analyst resigned over high-profile error

Grits had missed the news in August that a

DNA examiner resigned at the Forensic Science Commission after a

report by her employer found that she had testified incorrectly in a high-profile murder case in which a UT student was strangled, declaring the defendants' DNA could be excluded when that was not true. (She worked for DPS at the time she gave the testimony.) Though she told FSC investigators she "misspoke," she did so TEN times. The commission found that her error constituted professional "negligence," but not "misconduct." Whether or not there was any bad intention behind the mistake, it highlights the difficulties and

pitfalls of interpreting DNA mixture evidence, which is more subjective and less definitive than one-to-one DNA matching.

Can refined patrol strategies free up more officer time?

A criminologist at UT-Dallas

developed an algorithm to help the Carrollton PD refine its patrol strategies so officers waste less time in their vehicles. Notably, the

recent staffing study for Dallas PD similarly recommended refining patrol routes to free up officer time spent driving long distances.

Does EMS need tactical teams? Montgomery County thinks so

The Montgomery County Hospital District has

created a tactical team to join local police on SWAT raids. One paramedic said he joined the team because "There was more of the excitement appeal."

Alternative to police response for mental health, homelessness, substance abuse

Regular readers know that Austin recently

funded a new program to have medical personnel respond to some mental-health calls instead of police. At the same time, the city has been

engulfed in a debate over how to confront homelessness. A

program out of Oregon called CAHOOTS demonstrates an approach that could address both issues with a non-police response. Medical teams in a van respond to mental health crises and provide services to people suffering from substance abuse or homelessness, leaving law enforcement out of the equation. That's a great idea.

Okies boost parole rates

Parole rates in Oklahoma are

up 41 percent from last year, and commutations (which previously almost never happened) are up 1,300 percent,

reported the Tulsa World. Texas parole rates remain stagnant in recent years at around 35 percent. Most offenders in Texas prisons are parole-eligible and could be released today if the parole board agreed.

Policing practices parsed in Congress

The US House Judiciary Committee held a four-hour oversight hearing this week on policing practices.

Watch it here.

The public's cognitive dissonance over forensic science

A new

academic analysis finds that the public is losing faith in the accuracy of forensic science, but still believe forensics over other types of evidence. As evidence of this cognitive dissonance, "Respondents still believe that forensic evidence is a key part of a criminal case with nearly 40% of respondents believing that the absence of forensic evidence is sufficient for a prosecutor to drop the case and that the presence of forensic evidence,

even if other forms of evidence suggest that the defendant is not guilty, is enough to convict the defendant." (Emphasis added.)

A new constituency for pot legalization?

Should convenience-store owners become marijuana legalization proponents? It might boost their sales. A

academic analysis published in February found that legalizing recreational pot use resulted in increased junk food sales.

The eugenicist who gave us fingerprint identification

I didn't know that the original creator of fingerprint identification in the 19th century was also the enthusiastic

progenitor of the eugenics movement. It doesn't sound like the fingerprint discipline has changed much since he first convinced Scotland Yard to undertake it.

The criminogenic effect of police stops on black and Latino boys

A

study published in April found that "the frequency of police stops [of black and Latino teenage boys] predicted more frequent engagement in delinquent behavior 6, 12, and 18 mo later, whereas delinquent behavior did not predict subsequent reports of police stops." In other words, police stopping minority youth was predictive of future delinquency, but self-reported engagement in delinquency was NOT predictive of police stops! The implication is that proactive policing strategies like stop-and-frisk may actually cause juvenile crime instead of deterring it.

.jpg)