Showing posts with label Recidivism programs. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Recidivism programs. Show all posts

Thursday, October 05, 2017

Declines in TX recidivism led by parole success

Texas' recidivism rates are declining, according to this publication from the Council of State Governments Justice Center. According to them, parole revocations are down 33 percent since 2007, re-incarceration rates are down 25 percent, and rearrest rates are down 6 percent.

Reduced parole revocations are clearly the biggest success (and account for a big chunk of the decline in re-incarceration, as well). The document attributes those reductions to Texas' landmark legislation in 2007 which "Enhanced the use of parole for people at a low risk of reoffending and expanded the capacity of treatment and diversion programs," and "Expanded the capacity of substance use treatment programs and the use of intermediate sanction facilities to divert people from prison."

By contrast, probation revocations remained high. That same 2007 legislation included grants which were supposed to "Incentiviz[e] counties to create progressive sanctioning models for effective responses on probation." Some supposedly did, but unlike on the parole side, it didn't result in reduced revocations. Grits believes that's in part because the grants weren't structured to reduce if the desired outcomes weren't achieved. They just became part of probation departments' baseline funding, not an "incentive" to change behavior.

If Texas could figure out how to reduce probation revocations to the same extent we have for parole, we could close quite a few more prisons and save taxpayers a small fortune.

RELATED: See Texas' official recidivism data from the Legislative Budget Board.

Reduced parole revocations are clearly the biggest success (and account for a big chunk of the decline in re-incarceration, as well). The document attributes those reductions to Texas' landmark legislation in 2007 which "Enhanced the use of parole for people at a low risk of reoffending and expanded the capacity of treatment and diversion programs," and "Expanded the capacity of substance use treatment programs and the use of intermediate sanction facilities to divert people from prison."

By contrast, probation revocations remained high. That same 2007 legislation included grants which were supposed to "Incentiviz[e] counties to create progressive sanctioning models for effective responses on probation." Some supposedly did, but unlike on the parole side, it didn't result in reduced revocations. Grits believes that's in part because the grants weren't structured to reduce if the desired outcomes weren't achieved. They just became part of probation departments' baseline funding, not an "incentive" to change behavior.

If Texas could figure out how to reduce probation revocations to the same extent we have for parole, we could close quite a few more prisons and save taxpayers a small fortune.

RELATED: See Texas' official recidivism data from the Legislative Budget Board.

Labels:

Parole,

Probation,

Recidivism programs,

TDCJ

Sunday, September 10, 2017

Natural experiment tests rehabilitation potential for teen killers

|

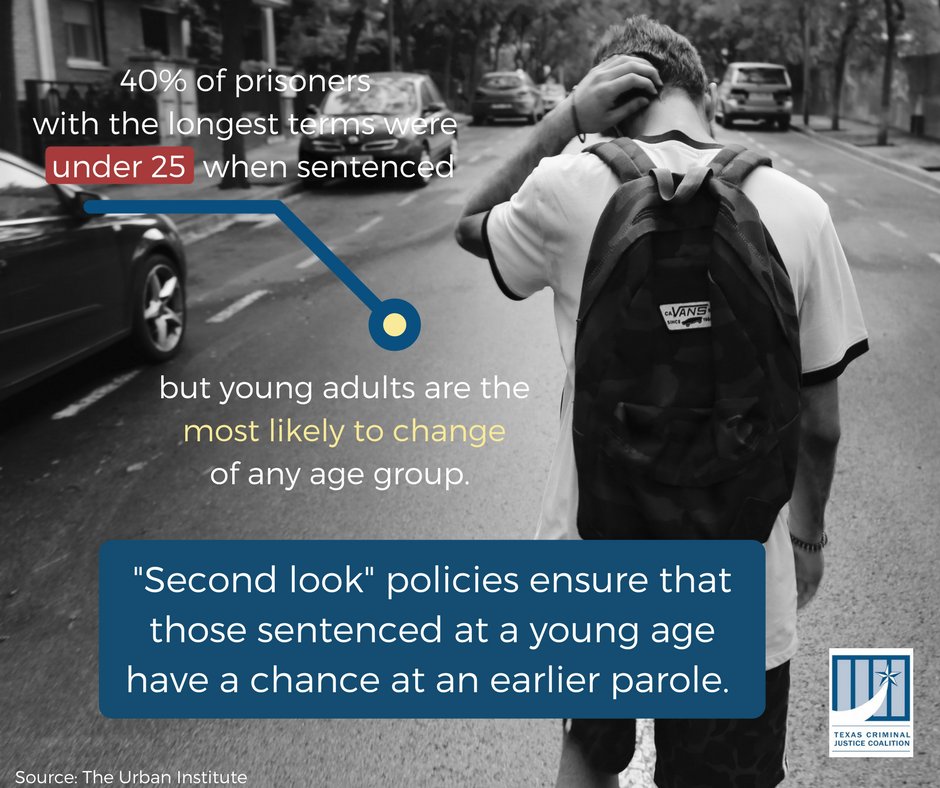

| Source: TCJC Twitter feed. |

During the 17-25 year old period, and particularly before age 21, neuroscientists now understand that young brains have yet to finish developing, especially as it relates to cognitive reasoning and impulse control. And some national experts have persuasively argued that the justice system needs to more effectively accommodate those differences in brain function.

So, in that vein, Grits was interested in this story out of the Phildadelphia Inquirer (9/7) detailing the fates of 70 released murderers who committed their crimes as young men and women. Like the defendant in Kentucky, they had served sentences for heinous crimes committed when they were teenagers. But they are now being released some two generations later. Here's how the story opened:

For the first time in a generation, Pennsylvania prisons are releasing convicted murderers by the dozen.

In the last year, 70 men and women — all locked away as teens — have quietly returned to the community after decades behind bars. They're landing their first jobs, as grocery store cashiers and line cooks, addiction counselors and paralegals. They are, in their 50s and 60s, learning to drive, renting their first apartments, trying to establish credit, and navigating unfamiliar relationships. They're encountering the mismatch between long-held daydreams and the hard realities of daily life.

These are the first of 517 juvenile lifers in Pennsylvania, the largest such contingent in the nation, to be resentenced and released on parole since the Supreme Court decided that mandatory life-without-parole sentences for minors are unconstitutional.The struggles facing these parolees perhaps are to be expected. If you'd been incarcerated since Smokey and the Bandit was in theaters, you'd face difficulty adjusting to 21st century America, as well. Regardless, "So far, not one of the 70 has violated parole."

Perhaps that should be expected, too. As it happens, murderers have among the lowest recidivism rates. And the judge out of Kentucky whom we discussed in our podcast cited this study in his ruling to say that, "ninety (90) percent of serious juvenile offenders age out of crime and do not continue criminal behavior into adulthood."

This represents a lot of folks. This summer, the Urban Institute issued a study which, the Marshall Project reported, found that two out of five inmates serving very long sentences committed their crimes before age 25. (See Grits' earlier discussion.)

There are a few different ways one could take into account these differences in youthful brain chemistry, and likely more Grits hasn't considered yet. My old pal Vinnie Schiraldi has suggested creating a separate third system to deal with 18-25 year olds (it'd be 17-25 in Texas, where we have not yet raise the age of adult culpability to 18). Elsewhere, some states like Connecticut are considering expanding their juvenile justice system to cover offenders up to age 21. Alternatively, Schiraldi has privately suggested to Grits that perhaps certain enhancements, barriers to reentry, etc., could be eliminated or reduced for younger offenders since their likelihood of rehabilitation is so much higher.

I'm sure there are other ways to skin this cat. We're on the front end of a national conversation about these topics spurred by recent scientific advancements. The suggestions for how to accommodate this new information remain prefatory and barely formed. But over time, as scientists better understand the human brain - and as the justice system slowly but surely adapts that knowledge to inform its various functions - it's not difficult to imagine major implications for these observations about brain development in a justice system based on identifying and punishing bad decisions, even if we can't say for sure what they'll be yet.

That said, inevitably, someone's parole will be revoked among this Pennsylvania cohort. The road to reentry is too difficult (as this article effectively described) and the array of humanity caught up in the system is too diverse for it to never happen. But prisoners who've served decades until they're now old men (and to a less common extent, women), especially if they had good behavior records while inside, are remarkably safe release risks compared to many younger inmates convicted of less serious offenses.

Sunday, January 08, 2017

Committee backs boosting programs to prevent recidivism

The section of the Texas House Corrections Committee interim report to the 84th Legislature on "recidivism" had some good elements, if not a groundbreaking analysis. Here are a few highlights:

First, it should be mentioned that Texas has among the lowest recidivism rates of any prison system, certainly among large states, in the United States. "Offenders released from prison in fiscal year 2011 had a rearrest rate of 46.5 percent, and a reincarceration rate of 21.4 percent within a three-year period," according to the report. Since in Texas one can be arrested for anything including Class C misdemeanors punishable only be fines, not jail time, many of those arrests are for petty stuff that may not really concern us from a safety perspective. Even so, that's a remarkably low rate; nationally, the rearrest rate is 67.8 percent. And our re-incarceration rate is also lower than the national average (55 percent within 5 years). Texas is one of a number of states where recidivism rates have been falling.

We've discussed before on Grits the reasons why, and it's not because we're doing such a great job of rehabilitating prisoners. Texas has the largest prison population among American states - greater even than California's whose civilian population is nearly half-again ours - and the reason is that we incarcerate more low-risk offenders who could be safely released than do other corrections systems where more rigorous cost-benefit analyses are applied to government activities.

Among some of the good news in the report was the decline in parole revocations for technical violations, which is due mainly to 1) Texas' 2007 reforms, including the creation of intermediate sanctions facilities, and 2) the changing makeup of and decisions by the parole board to reduce incarceration modestly. "In 2006, the Board of Pardons and Paroles revoked over ten thousand offenders. In fiscal year 2015, that number was reduced to about 5500." By contrast, revocations for technical violations on the probation side remain high - about half of all probation revocations.

First, it should be mentioned that Texas has among the lowest recidivism rates of any prison system, certainly among large states, in the United States. "Offenders released from prison in fiscal year 2011 had a rearrest rate of 46.5 percent, and a reincarceration rate of 21.4 percent within a three-year period," according to the report. Since in Texas one can be arrested for anything including Class C misdemeanors punishable only be fines, not jail time, many of those arrests are for petty stuff that may not really concern us from a safety perspective. Even so, that's a remarkably low rate; nationally, the rearrest rate is 67.8 percent. And our re-incarceration rate is also lower than the national average (55 percent within 5 years). Texas is one of a number of states where recidivism rates have been falling.

We've discussed before on Grits the reasons why, and it's not because we're doing such a great job of rehabilitating prisoners. Texas has the largest prison population among American states - greater even than California's whose civilian population is nearly half-again ours - and the reason is that we incarcerate more low-risk offenders who could be safely released than do other corrections systems where more rigorous cost-benefit analyses are applied to government activities.

At root, Texas' low recidivism rate mainly stems from the fact that we're over-incarcerating low-risk people to begin with - that many of those folks leaving prison were unlikely to have reoffended even if they'd remained free, and therefore they commit no new crimes when they get out, either. Reserving incarceration for people who pose a significant risk of harming others is a cost-benefit judgement at which the Texas system is not very good.

At present, Texas' system involves a great deal of churn on the low end, especially among drug users, with prisoners entering the system just long enough to receive a life-altering "felon" tag, maybe a prison tat or two and advice from career criminals on how not to get caught next time before being released. Then, on the back end, some elderly prisoners convicted of serious violent crimes are held too long after they no longer pose a big recidvism risk, with their healthcare costs driving up overall costs of incarceration. Both groups contribute to our low recidivism rates, but only because they wouldn't have committed more crimes whether incarcerated or not.

Among some of the good news in the report was the decline in parole revocations for technical violations, which is due mainly to 1) Texas' 2007 reforms, including the creation of intermediate sanctions facilities, and 2) the changing makeup of and decisions by the parole board to reduce incarceration modestly. "In 2006, the Board of Pardons and Paroles revoked over ten thousand offenders. In fiscal year 2015, that number was reduced to about 5500." By contrast, revocations for technical violations on the probation side remain high - about half of all probation revocations.

There's a good discussion in the report of in-prison programming and reentry support services which I won't replicate here but which may interest some readers. In the end, the committee recommended that, "Enhanced funding of Windham and correctional aftercare [for ex-prisoners who received drug and alcohol treatment] should be strongly considered next session." And they suggested that restrictions on occupational licenses for felons should be reevaluated "to exclude those

who have kept a clean record for a certain period of time."

Grits agrees with most of their observations about programming but would only caution to look at the recidivism data with big-picture nuance. If the Legislature stopped incarcerating low-risk offenders who're mainly imprisoned because they're drug addicts, for example, recidivism rates would likely go up over time. But that's only because a low-risk cadre has been removed and the remaining offenders are made up of predominantly higher-risk people. In the context of Texas' specific situation as it relates to over-incarceration, a rise in recidivism rates resulting from decarceration of low-risk offenders wouldn't be the worst thing in the world.

Labels:

Parole,

Recidivism programs,

TDCJ,

Windham School District

Monday, August 01, 2016

Harris pays more, gets worse safety outcomes from coercing pleas through detention of poor and innocent misdemeanor defendants

This new academic paper focused on Harris County, "The Downstream Consequences of Misdemeanor Pretrial Detention," has implications for innocence work as well as for local officials in Houston with budget-and-public-safety based motives to reduce pretrial detention. Here's the abstract:

In misdemeanor cases, pretrial detention poses a particular problem because it may induce otherwise innocent defendants to plead guilty in order to exit jail, potentially creating widespread error in case adjudication. While practitioners have long recognized this possibility, empirical evidence on the downstream impacts of pretrial detention on misdemeanor defendants and their cases remains limited. This Article uses detailed data on hundreds of thousands of misdemeanor cases resolved in Harris County, Texas — the third largest county in the U.S. — to measure the effects of pretrial detention on case outcomes and future crime. We find that detained defendants are 25% more likely than similarly situated releases to plead guilty, 43% more likely to be sentenced to jail, and receive jail sentences that are more than twice as long on average. Furthermore, those detained pretrial are more likely to commit future crime, suggesting that detention may have a criminogenic effect. These differences persist even after fully controlling for the initial bail amount as well as detailed offense, demographic, and criminal history characteristics. Use of more limited sets of controls, as in prior research, overstates the adverse impacts of detention. A quasi-experimental analysis based upon case timing confirms that these differences likely reflect the casual effect of detention. These results raise important constitutional questions, and suggest that Harris County could save millions of dollars a year, increase public safety, and reduce wrongful convictions with better pretrial release policy.

Saturday, April 30, 2016

Texas released 52% more violent offenders in 2014 than 2005

Texas prisons released 52 percent more prisoners convicted of violent offenses in FY 2014 than in FY 2005, according to the TDCJ annual statistical reports from those years. Comparing the number of people released in those two years we find:

Perhaps Texas' example provides evidence that the act of pursuing "low hanging fruit" in the political arena can help change the political culture surrounding crime and punishment in ways that indirectly affect debates and policies about violent offenders. (The same thing can happen, Grits would argue, with "innocence" and capital advocacy.)

For example, Texas' legislative reforms in 2007 focused almost exclusively on nonviolent drug and property offenses, with updating property-theft thresholds in 2015 the only other significant decarceration reform in recent memory. Yet the number of violent offenders released annually from TDCJ went up more than 50 percent.

The makeup of the parole board didn't change much over this period and nothing in the '07 bill would have caused that. (There were elements aimed at reducing parole revocations, but they wouldn't have affected releases.) Instead, the political culture changed around crime and punishment and the board reacted.

And, it must be said, even with that increase, release rates remain low. Though people convicted of violent offenses make up the majority of Texas prison inmates, they constituted only 22.6 percent of 2014 releases.

Still, when it comes to state-level decarceration reforms, Grits disagrees with Fordham law prof John Pfaff's tactical assessment about whether to prioritize reducing incarceration for nonviolent offenses. To me, the only practical place to start in the legislative arena, particularly in a red state like Texas, is on issues where it's possible to secure bipartisan support. One can't extract blood from stone.

But he's right to point out that real, long-term decarceration solutions necessarily must eventually extend to people deemed "violent" offenders. Otherwise, growth in that nebulous category can easily swallow up any decarceration gains from nonviolent offenders. For example, look at some top-line data from TDCJ Annual Statistical Reports for 2005 and 2014 (latest available), during which time the overall prison population decreased by 1,852. Within that total, though, there was wide variation.

Now let's look at only the new, incoming offenders in 2005 and 2014. With the number of new prison entries for property offenses nearly the same, the increase in new violent commitments entering Texas prisons in 2014 almost entirely offset the reduced number of new drug-offenders:

So I agree with Pfaff's central insight but sometimes think his commentary overstates how much the political process can do to reduce incarceration of violent felons, especially in states like Texas which already don't have mandatory minimums. The parole board (appointed to six year terms by the governor) and commissioners they hire make release decisions and there's not much outsiders can do to affect them.

Pfaff's focus on sentence length ignores areas where sentencing reform can make a difference. Any offense shifted from felony to misdemeanor status eliminates the possibility of imprisonment and keeps entire categories of offenders from ever entering TDCJ. Those low-level offenses are disproportionately drug and property crimes, so changing them won't affect the "violent" numbers. But they're something the Lege can actually affect that would reduce incarceration in the near term. They can't do much about parole rates.

Political tactics aren't just about plugging numbers into an equation or model to maximize marginal results. There are too many flawed humans with weird, self-interested agendas involved, and too many institutions with narrow jurisdictions that can only affect parts of the problem. I don't blame a New York City-based law prof for issuing theories which fail to take into account Texas' particular institutions and their realms of control.

It's hard to argue, though, with Pfaff's call for reassessing how offenders are judged along the violent-nonviolent axis:

I don't think Pfaff's analysis changes much of Texas reformers' strategy in the near term, but it's a caution to enthusiastic decarceration advocates to adjust expectations. For the foreseeable future, the much-ballyhooed national #Cut50 campaign remains a pipe dream, certainly in Texas. Without significantly slashing the numbers of violent offenders, it's not possible to get close to that number.

Grits can't say how we'll get there, if, or when. But I do know that politics is the art of the possible. And decarceration won't happen if advocates ignore the things which are possible to focus on things which are not.

In the meantime, the good news is that, in Texas, the parole board already is releasing more violent offenders, anyway, and with violent crime dropping and the economy booming, it turned out no one noticed, cared, nor complained.

TDCJ Releases 2005-2014:In fact, in 2012 Texas released 69.4 percent more violent offenders than in 2005, so this is not a new trend, and it has coincided with a decline in the state's violent crime rates over the same period. (Go here for an hypothesis why releasing so many more "violent offenders" didn't increase crime.)

Violent: 5,521 up

Property: 632 up

Drug: 2,756 down

Other: 2,612 up

Perhaps Texas' example provides evidence that the act of pursuing "low hanging fruit" in the political arena can help change the political culture surrounding crime and punishment in ways that indirectly affect debates and policies about violent offenders. (The same thing can happen, Grits would argue, with "innocence" and capital advocacy.)

For example, Texas' legislative reforms in 2007 focused almost exclusively on nonviolent drug and property offenses, with updating property-theft thresholds in 2015 the only other significant decarceration reform in recent memory. Yet the number of violent offenders released annually from TDCJ went up more than 50 percent.

The makeup of the parole board didn't change much over this period and nothing in the '07 bill would have caused that. (There were elements aimed at reducing parole revocations, but they wouldn't have affected releases.) Instead, the political culture changed around crime and punishment and the board reacted.

And, it must be said, even with that increase, release rates remain low. Though people convicted of violent offenses make up the majority of Texas prison inmates, they constituted only 22.6 percent of 2014 releases.

Still, when it comes to state-level decarceration reforms, Grits disagrees with Fordham law prof John Pfaff's tactical assessment about whether to prioritize reducing incarceration for nonviolent offenses. To me, the only practical place to start in the legislative arena, particularly in a red state like Texas, is on issues where it's possible to secure bipartisan support. One can't extract blood from stone.

But he's right to point out that real, long-term decarceration solutions necessarily must eventually extend to people deemed "violent" offenders. Otherwise, growth in that nebulous category can easily swallow up any decarceration gains from nonviolent offenders. For example, look at some top-line data from TDCJ Annual Statistical Reports for 2005 and 2014 (latest available), during which time the overall prison population decreased by 1,852. Within that total, though, there was wide variation.

TDCJ On-hand:Reductions achieved in property and drug offender totals were nearly entirely offset by the increased number of violent offenders, who as of Aug. 31, 2014 made up 55.6 percent of TDCJ's population totals.

Violent: 10,396 up

Property: 4,643 down

Drug: 5,679 down

Other: 1,299 up

Now let's look at only the new, incoming offenders in 2005 and 2014. With the number of new prison entries for property offenses nearly the same, the increase in new violent commitments entering Texas prisons in 2014 almost entirely offset the reduced number of new drug-offenders:

TDCJ Receives:The difference is, violent offenders tend to have longer sentences, so the new violent offenders will take up prison space for more bed-years over time. TDCJ essentially soaked up another placement for a violent offense for every drug and property offender diverted.

Violent: 3,616 up

Property: 212 up

Drug: 3,808 down

Other: 2,821 up

So I agree with Pfaff's central insight but sometimes think his commentary overstates how much the political process can do to reduce incarceration of violent felons, especially in states like Texas which already don't have mandatory minimums. The parole board (appointed to six year terms by the governor) and commissioners they hire make release decisions and there's not much outsiders can do to affect them.

Pfaff's focus on sentence length ignores areas where sentencing reform can make a difference. Any offense shifted from felony to misdemeanor status eliminates the possibility of imprisonment and keeps entire categories of offenders from ever entering TDCJ. Those low-level offenses are disproportionately drug and property crimes, so changing them won't affect the "violent" numbers. But they're something the Lege can actually affect that would reduce incarceration in the near term. They can't do much about parole rates.

Political tactics aren't just about plugging numbers into an equation or model to maximize marginal results. There are too many flawed humans with weird, self-interested agendas involved, and too many institutions with narrow jurisdictions that can only affect parts of the problem. I don't blame a New York City-based law prof for issuing theories which fail to take into account Texas' particular institutions and their realms of control.

It's hard to argue, though, with Pfaff's call for reassessing how offenders are judged along the violent-nonviolent axis:

Pfaff added that the division of inmates into non-violent and violent is itself confusing and misleading. “Not all violent offenders are really all that violent, and not all non-violent are necessarily non-violent; it’s tricky to figure out who is who,” he said.That's right, but it's a far cry from what either the public or the political class believe at this particular historical moment. In the scheme of things, it wasn't very long ago that even recommending leniency for "nonviolent" offenders was a political nonstarter in this state and many others. That's easy to forget in the wake of the post-Ferguson focus on criminal justice reform in the last however-many months. Maybe there will be things possible going forward that in the past would have fallen outside the bounds of mainstream political debate. But it would be wrong to critique strategic and tactical decisions before that time based on what's possible going forward. Those are different things.

For example, Pfaff said, in New York state, burglars who break into a house when no one is home are still considered violent offenders. On the other hand, when Pfaff examined records of non-violent drug offenders, he found that many had a record of violent crimes from the past, or had physically harmed someone during the commission of their crimes.Focusing on non-violent crime, then, is actually a somewhat arbitrary way to separate the incarcerated into good prisoners and bad prisoners—and to avoid dealing with the most pernicious ideology behind the incarceration binge.“As long as we focus on non-violent people in prison,” Pfaff told Quartz, “it has the collateral consequence of suggesting we should just give up on the violent people, and that the violent people deserve whatever we do. And I’m not sure that’s entirely the right way to think about it. Violent people change, violent people age out of crime.”

I don't think Pfaff's analysis changes much of Texas reformers' strategy in the near term, but it's a caution to enthusiastic decarceration advocates to adjust expectations. For the foreseeable future, the much-ballyhooed national #Cut50 campaign remains a pipe dream, certainly in Texas. Without significantly slashing the numbers of violent offenders, it's not possible to get close to that number.

Grits can't say how we'll get there, if, or when. But I do know that politics is the art of the possible. And decarceration won't happen if advocates ignore the things which are possible to focus on things which are not.

In the meantime, the good news is that, in Texas, the parole board already is releasing more violent offenders, anyway, and with violent crime dropping and the economy booming, it turned out no one noticed, cared, nor complained.

Labels:

Parole,

Recidivism programs,

TDCJ

Saturday, February 06, 2016

Previewing interim charges at House Corrections Committee

The Texas House Corrections Committee will meet Tuesday and Wednesday to discuss an array of interim charges, so lets preview each of them ahead of time. First up on Tuesday:

Reducing drug offenders in prison

On incarceration rates for nonviolent drug offenders in Texas state prisons, the go-to source is the TDCJ Annual Statistical report; here's the FY 2014 version. According to that source, about 16 percent of TDCJ offenders on hand as of Aug. 31, 2014 were incarcerated for a drug offense as the primary charge, or 24,005 inmates out of roughly 150,000 incarcerated in TDCJ that day. Of those, 14,256 were incarcerated for possession only and 9,699 for drug delivery. Of the subset of those locked up in state jails (essentially fourth-degree felons), the same report found 37 percent were incarcerated for a drug offense, almost all of them (90 percent) for possession.

Notably, there were 1,998 inmates with a drug offense as their primary charge who are categorized by TDCJ as 3g offenders, a category largely reserved for violent crimes. The reference is to Sec. 42.12(3)(g) of the Code of Criminal Procedure. Drug offenses become 3g offenses if a child was present or involved or if the offense were committed in a drug free zone. While we may not like these drug offenders, its probably unhelpful to group them with murderers. This might be an example of people serving unnecessary extra time because we're "mad at" them, not afraid of them, as Sen. John Whitmire is fond of saying.

As far as the costs of housing drug offenders, the uniform cost report document prepared biennially by the Legislative Budget Board is the go-to source. They put the average FY 2014 cost at $54.89 per day.

OTOH, in truth, how much it costs to house a prisoner varies widely based on what unit they're housed in, whether they receive drug treatment, education, or other services, and whether they get sick, among other things. Recently Grits requested breakdown of the cost per prisoner at all TDCJ units as of 2014. (Thanks to TDCJ Public Information Officer Jason Clark for fulfilling that request.)

Looking at that level of detail, we can see, for example, that SAFP services delivered at the Jester I unit (built in 1885) cost $90.85 compared to an average of $58.72 at the four other units delivering SAFP services. These unit-by-unit data give a clearer sense of how widely costs can vary per prisoner depending on where they're housed. The $55 average LBB uses masks a wide range of differences and could be lowered by closing some of those higher-cost facilities.

As for alternatives to incarceration, my hope would be that debates could move beyond drug courts to the need to adjust drug sentences for low-level possession downward. Texas has invested a great deal in drug courts and proven conclusively that strong probation works. But the resource-intensive tactic cannot scale up to handle the volume of drug offenders cycling in and out of the system at all levels.

Thus, as the committee contemplates alternatives to incarceration, it's worth considering whether offenders caught with four grams or less of a controlled substances should be treated as felons at all, considering all the job and housing implications and other the collateral consequences a felony label entails. Shifting penalties to a Class A misdemeanor for up to four grams of a controlled substance would save the state big money and dramatically reduce collateral consequences for those low-level offenders.

How much money could be saved from reduced penalties? Last session, Rep. Senfronia Thompson proposed HB 254, which would have reduced the sentencing category for people possession less than a gram of a controlled substance, so a subset of the up-to-four-grams category. The Legislative Budget Board estimated that the state would save more than $105 million in the first biennium and upwards of $139 million in the second. If sentences for up to four grams were reduced to a Class A misdemeanor, the reduction in the incarceration budget would be even greater.

Those levels of savings could finance an impressive amount of treatment and diversion programming for these new Class A drug offenders, nearly all of whom would inevitably receive probation (just like most Class A drug offenders do now). Once the Comptroller certifies the savings, some or all of it could be diverted to probation departments to pay for additional treatment services and possibly reduce the portion of probation budgets paid for by probationer fees, an issue getting increasing levels of attention lately.

Last session the Legislature boosted TDCJ's budget by more than $400 million, which seemed like a remarkable amount for a bunch of self-styled fiscal conservatives to spend on a Big Government program with no clear extra benefit in public safety effectiveness. (Of course, the same can be said of the border surge.) And that doesn't include the portion of corrections spending outside of TDCJ's budget. In a fiscal environment where oil revenues are down and legislators will be looking for cuts, not increases, the best way to pay for alternatives to incarceration would be sentence reductions, which themselves constitute an "alternative" to sending low-level drug addicts to state prison.

Inmate release policies and ad seg

Regarding releasing inmates directly from ad seg, Grits has addressed this question previously and refer readers to those related posts. Texas recently had its first prisoner pass the 30 year mark in solitary confinement, which seems outlandish except that he won't be the last. As of 2014, Texas had more prisoners in solitary confinement than the entire prison populations in 12 states. The union for correctional officers has claimed excessive use of solitary is responsible for higher assault rates on prison staff.

Staffers preparing their legislators on these issues may want to check out a new report on solitary confinement titled "Time in Cell" and a series of essays published recently in the Yale Law Journal reacting to its findings. Also, Texas figured prominently in a Marshall Project story from last year related to inmates released directly from solitary.

Also relevant: Last year the United Nations issued the Mandela Rules related to the use of solitary confinement which include some relevant suggestions. Those rules emphasize that the period of imprisonment should be "used to ensure, so far as possible, the reintegration of such persons into society upon release so that they can lead a law-abiding and self-supporting life." When prisoners who've been in solitary are released, "the prison administration shall take the necessary measures to alleviate the potential detrimental effects of their confinement on them and on their community following their release from prison."

The Mandela Rules suggest a step-down pre-release strategy which at present is foreign to TDCJ's programs and culture.

Understanding recidivism, planning for reentry

The interim "charge" up on Wednesday really addresses two separate but related issues: recidivism and reentry. This LBB report is the go-to document for recidivism data. For the cohort of prisoners released in 2011, the proportion rearrested within three years was:

If Texas commits to a strategy of de-incarceration, in all likelihood recidivism rates will rise. But that's a sign of normalization, not of failure. The day we're really limiting incarceration to those we're "afraid of" as opposed to people we're mad at, those we're "afraid of" who're released will, as a class, recidivate more. But that's not an argument for locking up low-risk offenders!

As to reentry questions - which are related to but separate from the recidivism debate - legislators could do worse than to look again to the Mandela Rules, cited above, which advise that, "The duty of society does not end with a prisoner’s release. There should, therefore, be governmental or private agencies capable of lending the released prisoner efficient aftercare directed towards the lessening of prejudice against him or her and towards his or her social rehabilitation." In Texas by contrast, released prisoners are given $100 in "gate money" and a bus ticket.

The committee should look at some of the barriers to successful reentry, like restriction on TANF benefits and food stamps for certain drug offenders discussed in a Grits post earlier today. I'd also like to see the committee look for policies to reduce the accumulation of fines, fees, and debts facing ex-prisoners upon reentry. And there should be more focus on reducing the burden on families when their loved ones come home from prison.

The two biggest barriers to reentry, though, remain housing and jobs. These are difficult problems which don't lend themselves to simple solutions. In fact, it's hard to imagine making a dent in either without some state investment, which as mentioned runs counter to an oil-starved budget environment. And yet, if the Legislature doesn't address these questions then we're not being honest about the often state-created barriers to reentry facing ex-offenders.

The Lege eliminated job assistance for ex-prisoners during the 2011 budget crunch and has declined to limit the extent landlords can discriminate against ex-offenders regarding housing, even though one in five Americans has some sort of criminal record. In the past, efforts to expand reentry housing opportunities have been too quickly scuttled in response to NIMBY backlash. Legislators will need to pony up money for jobs programs and other reentry services and stand up to NIMBY opposition over housing to make much more headway on reentry questions. These problems are fairly well understood, but they'll require unusual political courage and money to honestly address them.

MORE: Grits contributing writer Michele Deitch emailed to say:

- Study incarceration rates for non-violent drug offenses and the cost to the state associated with those offenses. Identify alternatives to incarceration, including community supervision, that could be used to reduce incarceration rates of non-violent drug offenders.

- Study inmate release policies of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, including the release of inmates directly from administrative segregation. Identify best practices and policies for the transitioning of these various inmate populations from the prison to appropriate supervision in the community. Identify any needed legislative changes necessary to accomplish these goals.

Study recidivism, its major causes, and existing programs designed to reduce recidivism, including a review of current programs utilized by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) and the Windham School District for incarcerated persons. Examine re-entry programs and opportunities for offenders upon release. Identify successful programs in other jurisdictions and consider how they might be implemented in Texas.Let's walk through be basics on these.

Reducing drug offenders in prison

On incarceration rates for nonviolent drug offenders in Texas state prisons, the go-to source is the TDCJ Annual Statistical report; here's the FY 2014 version. According to that source, about 16 percent of TDCJ offenders on hand as of Aug. 31, 2014 were incarcerated for a drug offense as the primary charge, or 24,005 inmates out of roughly 150,000 incarcerated in TDCJ that day. Of those, 14,256 were incarcerated for possession only and 9,699 for drug delivery. Of the subset of those locked up in state jails (essentially fourth-degree felons), the same report found 37 percent were incarcerated for a drug offense, almost all of them (90 percent) for possession.

Notably, there were 1,998 inmates with a drug offense as their primary charge who are categorized by TDCJ as 3g offenders, a category largely reserved for violent crimes. The reference is to Sec. 42.12(3)(g) of the Code of Criminal Procedure. Drug offenses become 3g offenses if a child was present or involved or if the offense were committed in a drug free zone. While we may not like these drug offenders, its probably unhelpful to group them with murderers. This might be an example of people serving unnecessary extra time because we're "mad at" them, not afraid of them, as Sen. John Whitmire is fond of saying.

As far as the costs of housing drug offenders, the uniform cost report document prepared biennially by the Legislative Budget Board is the go-to source. They put the average FY 2014 cost at $54.89 per day.

OTOH, in truth, how much it costs to house a prisoner varies widely based on what unit they're housed in, whether they receive drug treatment, education, or other services, and whether they get sick, among other things. Recently Grits requested breakdown of the cost per prisoner at all TDCJ units as of 2014. (Thanks to TDCJ Public Information Officer Jason Clark for fulfilling that request.)

Looking at that level of detail, we can see, for example, that SAFP services delivered at the Jester I unit (built in 1885) cost $90.85 compared to an average of $58.72 at the four other units delivering SAFP services. These unit-by-unit data give a clearer sense of how widely costs can vary per prisoner depending on where they're housed. The $55 average LBB uses masks a wide range of differences and could be lowered by closing some of those higher-cost facilities.

As for alternatives to incarceration, my hope would be that debates could move beyond drug courts to the need to adjust drug sentences for low-level possession downward. Texas has invested a great deal in drug courts and proven conclusively that strong probation works. But the resource-intensive tactic cannot scale up to handle the volume of drug offenders cycling in and out of the system at all levels.

Thus, as the committee contemplates alternatives to incarceration, it's worth considering whether offenders caught with four grams or less of a controlled substances should be treated as felons at all, considering all the job and housing implications and other the collateral consequences a felony label entails. Shifting penalties to a Class A misdemeanor for up to four grams of a controlled substance would save the state big money and dramatically reduce collateral consequences for those low-level offenders.

How much money could be saved from reduced penalties? Last session, Rep. Senfronia Thompson proposed HB 254, which would have reduced the sentencing category for people possession less than a gram of a controlled substance, so a subset of the up-to-four-grams category. The Legislative Budget Board estimated that the state would save more than $105 million in the first biennium and upwards of $139 million in the second. If sentences for up to four grams were reduced to a Class A misdemeanor, the reduction in the incarceration budget would be even greater.

Those levels of savings could finance an impressive amount of treatment and diversion programming for these new Class A drug offenders, nearly all of whom would inevitably receive probation (just like most Class A drug offenders do now). Once the Comptroller certifies the savings, some or all of it could be diverted to probation departments to pay for additional treatment services and possibly reduce the portion of probation budgets paid for by probationer fees, an issue getting increasing levels of attention lately.

Last session the Legislature boosted TDCJ's budget by more than $400 million, which seemed like a remarkable amount for a bunch of self-styled fiscal conservatives to spend on a Big Government program with no clear extra benefit in public safety effectiveness. (Of course, the same can be said of the border surge.) And that doesn't include the portion of corrections spending outside of TDCJ's budget. In a fiscal environment where oil revenues are down and legislators will be looking for cuts, not increases, the best way to pay for alternatives to incarceration would be sentence reductions, which themselves constitute an "alternative" to sending low-level drug addicts to state prison.

Inmate release policies and ad seg

Regarding releasing inmates directly from ad seg, Grits has addressed this question previously and refer readers to those related posts. Texas recently had its first prisoner pass the 30 year mark in solitary confinement, which seems outlandish except that he won't be the last. As of 2014, Texas had more prisoners in solitary confinement than the entire prison populations in 12 states. The union for correctional officers has claimed excessive use of solitary is responsible for higher assault rates on prison staff.

Staffers preparing their legislators on these issues may want to check out a new report on solitary confinement titled "Time in Cell" and a series of essays published recently in the Yale Law Journal reacting to its findings. Also, Texas figured prominently in a Marshall Project story from last year related to inmates released directly from solitary.

Also relevant: Last year the United Nations issued the Mandela Rules related to the use of solitary confinement which include some relevant suggestions. Those rules emphasize that the period of imprisonment should be "used to ensure, so far as possible, the reintegration of such persons into society upon release so that they can lead a law-abiding and self-supporting life." When prisoners who've been in solitary are released, "the prison administration shall take the necessary measures to alleviate the potential detrimental effects of their confinement on them and on their community following their release from prison."

The Mandela Rules suggest a step-down pre-release strategy which at present is foreign to TDCJ's programs and culture.

Before the completion of the sentence, it is desirable that the necessary steps be taken to ensure for the prisoner a gradual return to life in society. This aim may be achieved, depending on the case, by a pre-release regime organized in the same prison or in another appropriate institution, or by release on trial under some kind of supervision which must not be entrusted to the police but should be combined with effective social aid.Whether or not Texas fully adopts the Mandela Rules, that particular suggestion makes a lot of sense.

Understanding recidivism, planning for reentry

The interim "charge" up on Wednesday really addresses two separate but related issues: recidivism and reentry. This LBB report is the go-to document for recidivism data. For the cohort of prisoners released in 2011, the proportion rearrested within three years was:

- Prison: 46.5%

- State Jail: 62.0%

- Intermediate Sanction Facility: 57.5%

- Prison: 21.4%

- State Jail: 30.7%

- Intermediate Sanction Facility: 36.5%

If Texas commits to a strategy of de-incarceration, in all likelihood recidivism rates will rise. But that's a sign of normalization, not of failure. The day we're really limiting incarceration to those we're "afraid of" as opposed to people we're mad at, those we're "afraid of" who're released will, as a class, recidivate more. But that's not an argument for locking up low-risk offenders!

As to reentry questions - which are related to but separate from the recidivism debate - legislators could do worse than to look again to the Mandela Rules, cited above, which advise that, "The duty of society does not end with a prisoner’s release. There should, therefore, be governmental or private agencies capable of lending the released prisoner efficient aftercare directed towards the lessening of prejudice against him or her and towards his or her social rehabilitation." In Texas by contrast, released prisoners are given $100 in "gate money" and a bus ticket.

The committee should look at some of the barriers to successful reentry, like restriction on TANF benefits and food stamps for certain drug offenders discussed in a Grits post earlier today. I'd also like to see the committee look for policies to reduce the accumulation of fines, fees, and debts facing ex-prisoners upon reentry. And there should be more focus on reducing the burden on families when their loved ones come home from prison.

The two biggest barriers to reentry, though, remain housing and jobs. These are difficult problems which don't lend themselves to simple solutions. In fact, it's hard to imagine making a dent in either without some state investment, which as mentioned runs counter to an oil-starved budget environment. And yet, if the Legislature doesn't address these questions then we're not being honest about the often state-created barriers to reentry facing ex-offenders.

The Lege eliminated job assistance for ex-prisoners during the 2011 budget crunch and has declined to limit the extent landlords can discriminate against ex-offenders regarding housing, even though one in five Americans has some sort of criminal record. In the past, efforts to expand reentry housing opportunities have been too quickly scuttled in response to NIMBY backlash. Legislators will need to pony up money for jobs programs and other reentry services and stand up to NIMBY opposition over housing to make much more headway on reentry questions. These problems are fairly well understood, but they'll require unusual political courage and money to honestly address them.

MORE: Grits contributing writer Michele Deitch emailed to say:

I wanted to flag for you that the Lege doesn't even have to reach to an international source like the Mandela Rules for guidance on this issue. The ABA's Standards on the Treatment of Prisoners provide similar guidance as to the need for step-down type approaches. Here is a link to the ABA Standards.

You would want to look at Standards 23-2.6, 2.7, 2.8, 2.9, and 3.8, all of which deal with seg issues. Pay particular attention to 2.9, which addresses procedures for placement and retention in long-term segregated housing, and especially subsection (f), which addresses the need for a less-restrictive setting in the months before release to the community. The drafters definitely had in mind a step-down type approach to segregated housing. (As the original drafter, I can say that with some authority! :) )

Labels:

ad seg,

drug policy,

Recidivism programs,

reentry,

TDCJ

Wednesday, July 15, 2015

Some TDCJ treatment programs increase recidivism

A friend forwarded me a copy of this recidivism analysis from Texas Department of Criminal Justice prison rehabilitation programs, lamenting that "some of the TDCJ rehabilitation programs demonstrably make people worse."

Which ones? Four of nine programs showed participants' recidivism increased after two years in the free world, though after three years only two programs - specifically the Sex Offender Treatment Program and the Pre-Release Substance Abuse Program, the latter of which has consistently resulted in increased recidivism since the agency began studying it - displayed higher recidivism rates.

The two programs with worse outcomes after two years that came out slightly better after three were the Sex Offender Education Program and the Serious and Violent Offender Reentry Initiative.

The SAFP program is the TDCJ rehab program with the best results and was the only one to make a double-digit difference.

Which ones? Four of nine programs showed participants' recidivism increased after two years in the free world, though after three years only two programs - specifically the Sex Offender Treatment Program and the Pre-Release Substance Abuse Program, the latter of which has consistently resulted in increased recidivism since the agency began studying it - displayed higher recidivism rates.

The two programs with worse outcomes after two years that came out slightly better after three were the Sex Offender Education Program and the Serious and Violent Offender Reentry Initiative.

The SAFP program is the TDCJ rehab program with the best results and was the only one to make a double-digit difference.

Labels:

Recidivism programs

Monday, April 20, 2015

Bill to reduce recidivism, increase state-jail felon program participation would save state $227.7 million

The Texas House last week approved a nice little bill by Rep. Alma Allen, HB 1546, which would save the state $227.7 million over the next five years by reducing incarceration for state jail felons by a few months if they participate in programming, according the Legislative Budget Board. The savings in the first biennium would be $81 million. The proposed tweak to the law would have the state corrections agency apply "diligent participation credits" toward reduction of inmates' state jail felony sentences - up to 20 percent of the sentence - which are otherwise served day for day without possibility of parole or early release. (My colleague Sarah Pahl at the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition has been working hard on this bill.)

The bill passed 141-0 (with a couple of members recording opposition in the journal after the fact) and no opposition in committee. Its companion legislation, SB 589 by Rodriguez/Hinojosa, has already passed out of the Senate Criminal Justice Committee and is on the Intent Calendar. So the Senate could finally approve this bill pretty quickly if the votes are there.

Presently, it's possible but unlikely for state jail inmates to receive sentence reductions based on participation in educational or treatment programs. TDCJ sends judges information about program participation months after the case is over when the defendant's sentence is almost complete, creating a cumbersome and time consuming extra process for the courts for this class of low-level, mostly non-violent offenders. "The court then has to receive and process the request, make a decision about awarding credit to the inmate, and return the report to TDCJ," explained the House Research Organization analysis. Presently, judges do not reply to TDCJ in more than half of cases and in others the decision comes too late to result in a meaningful reduction in the sentence. In other words, the process now is basically dysfunctional.

State jail felons have a higher recidivism rate than other inmates leaving TDCJ and also are not under supervision when they leave, having served a day-for-day sentence. So anything which can be done to reduce recidivism for this category of offenders would be welcome; presently the state has few tools to influence their behavior beyond locking them up for a short time. A few months reduction in state jail felony sentences - already measured in months, not years - is a significant incentive for inmates to participate in programming which reduces recidivism.

These folks will soon be released regardless after spending 6-24 months (max) incarcerated in a Texas state jail felony facility. So the question isn't whether we should "keep them locked up." They'll be released soon enough, either way. The question is whether they'll have done anything productive with their time while they're inside, which this bill incentivizes and prioritizes.

The Senate this year has been all about spending caps but we've heard barely a peep from them about budget cuts. Here's a chance to save nearly a quarter billion dollars over the next five years while reducing both incarceration and recidivism among nonviolent offenders. What's not to like?

The bill passed 141-0 (with a couple of members recording opposition in the journal after the fact) and no opposition in committee. Its companion legislation, SB 589 by Rodriguez/Hinojosa, has already passed out of the Senate Criminal Justice Committee and is on the Intent Calendar. So the Senate could finally approve this bill pretty quickly if the votes are there.

Presently, it's possible but unlikely for state jail inmates to receive sentence reductions based on participation in educational or treatment programs. TDCJ sends judges information about program participation months after the case is over when the defendant's sentence is almost complete, creating a cumbersome and time consuming extra process for the courts for this class of low-level, mostly non-violent offenders. "The court then has to receive and process the request, make a decision about awarding credit to the inmate, and return the report to TDCJ," explained the House Research Organization analysis. Presently, judges do not reply to TDCJ in more than half of cases and in others the decision comes too late to result in a meaningful reduction in the sentence. In other words, the process now is basically dysfunctional.

State jail felons have a higher recidivism rate than other inmates leaving TDCJ and also are not under supervision when they leave, having served a day-for-day sentence. So anything which can be done to reduce recidivism for this category of offenders would be welcome; presently the state has few tools to influence their behavior beyond locking them up for a short time. A few months reduction in state jail felony sentences - already measured in months, not years - is a significant incentive for inmates to participate in programming which reduces recidivism.

These folks will soon be released regardless after spending 6-24 months (max) incarcerated in a Texas state jail felony facility. So the question isn't whether we should "keep them locked up." They'll be released soon enough, either way. The question is whether they'll have done anything productive with their time while they're inside, which this bill incentivizes and prioritizes.

The Senate this year has been all about spending caps but we've heard barely a peep from them about budget cuts. Here's a chance to save nearly a quarter billion dollars over the next five years while reducing both incarceration and recidivism among nonviolent offenders. What's not to like?

Saturday, August 23, 2014

Healthcare at reentry helps prevent recidivism

This article from Medicine@Yale makes an argument Grits has posited before, particularly as it relates to mental health services: That expanding Medicaid - in particular providing care to indigent ex-cons and covering hospital costs for prisoners - would reduce both costs and recidivism while improving public safety. Inmates leaving prison "don’t know how to find health insurance or medical care. And many

quickly wind up in emergency departments with overdoses or exacerbations

of chronic diseases that were being treated in prison."

“Obamacare is key to reducing recidivism,” [Dr. Emily] Wang says. She adds, however, that the reverse is also true. Over one-fifth of people eligible for Medicaid under the ACA expansion are incarcerated, on probation, or on parole. Many are young and healthy, making them attractive to insurance companies looking to dilute their risk pools. Far from being burdensome, then, these individuals may strengthen the health care system—much as their involvement has made the TCN more effective.Speaking of the intersection between healthcare and reentry, a story on NPR this week lauded San Antonio's proactive approach to mental health, fielding specially trained officers to deal with the mentally ill and establishing an effective diversion program to keep them out of the system. The key was for stakeholders to chip in to

“In order for the Affordable Care Act to work,” Wang says, “you have to get former prisoners involved.”

create the Restoration Center. It offers a 48-hour inpatient psychiatric unit; outpatient services for psychiatric and primary care; centers for drug or alcohol detox; a 90-day recovery program for substance abuse; plus housing for people with mental illnesses, and even job training.

More than 18,000 people pass through the Restoration Center each year, and officials say the coordinated approach has saved the city more than $10 million annually.

Labels:

frequent flyers,

Health,

Medicaid,

Mental health,

Recidivism programs

Wednesday, April 30, 2014

TPPF in the news: Reducing technical revocations, clarifying recidivism data

A couple of recent Texas Public Policy Foundation reports got good press coverage this week:

In the report on supervision tech, I particularly liked this suggestion for reducing incarceration based on technical violations of petty absconders:

In the comments to the Trib story, I offered one minor but important correction. The reporter had written that "Sixty-two percent of all Texas inmates return to prison within three years of their release. But that's not quite right.

Looking at the TPPF report, it says 62% of state jail inmates, not "all Texas inmates" are rearrested within three years, not "return to prison." State jail inmates have the highest recidivism rates of all prisoners, in part because they serve sentences day for day and leave without any post-incarceration supervision.

According to the Legislative Budget Board's latest report on the topic titled "Statewide Criminal Justice Recidivism and Revocation Rates" (pdf), the percentage of Texas prisoners who return to prison after three years was 22.6% for the most recent cohort - far lower than the national average. Among state jail inmates the number returning to prison is slightly higher - 31.1%.

The difference between rearrest and re-incarceration numbers is significant. After all, in Texas you can be arrested for a Class C misdemeanor, so many ex-offenders who are rearrested for minor offenses within three years of release do not actually return to prison.

UPDATE: The Tribune has updated its story to correct the error.

- Texas Tribune: "Lawmakers urged to reform parole with technology"

- Report: Cutting Edge Corrections: Using technology to improve community supervision in Texas

- Texas Observer: "The conservative case against locking up minors"

- Report: Kids doing time for what's not a crime: The over-incarceration of status offenders

In the report on supervision tech, I particularly liked this suggestion for reducing incarceration based on technical violations of petty absconders:

Currently, there are more than 24,000 felony probation absconders in Texas. While they may succeed for a time in skirting their obligations to report to a probation officer when they are pulled over for a traffic violation or are otherwise apprehended, they will face the prospect of being revoked to prison. At least 35 percent of probationers revoked for technical violations (where there is no allegation of a new offense) were classified as absconders at the time. Based on the 12,287 total technical revocations in 2013, this amounts to at least 4,300 technical revocations associated with absconders, which translates into annual incarceration costs of $79 million, not counting the compounding effect over time as the revocation time served will exceed a year in most cases.Recidivism clarification

This analysis demonstrates the potential of utilizing GPS to reduce the number of technical revocations. Given that any type of GPS monitoring costs a fraction of the $50.49 per day prison cost, it is a particularly sensible option for those who were placed on probation for a non-violent offense and have failed to report, but are not assessed as a high risk of re-offending. (Citations omitted.)

In the comments to the Trib story, I offered one minor but important correction. The reporter had written that "Sixty-two percent of all Texas inmates return to prison within three years of their release. But that's not quite right.

Looking at the TPPF report, it says 62% of state jail inmates, not "all Texas inmates" are rearrested within three years, not "return to prison." State jail inmates have the highest recidivism rates of all prisoners, in part because they serve sentences day for day and leave without any post-incarceration supervision.

According to the Legislative Budget Board's latest report on the topic titled "Statewide Criminal Justice Recidivism and Revocation Rates" (pdf), the percentage of Texas prisoners who return to prison after three years was 22.6% for the most recent cohort - far lower than the national average. Among state jail inmates the number returning to prison is slightly higher - 31.1%.

The difference between rearrest and re-incarceration numbers is significant. After all, in Texas you can be arrested for a Class C misdemeanor, so many ex-offenders who are rearrested for minor offenses within three years of release do not actually return to prison.

UPDATE: The Tribune has updated its story to correct the error.

Labels:

GPS,

juvie corrections,

Parole,

Probation,

Recidivism programs,

technocorrections

Thursday, December 19, 2013

Cornyn: Reform federal prisons based on Texas model

Texas' US Sen. John Cornyn this month introduced federal legislation, S. 1783, styled the Federal Prison Reform Act of 2013, that he says is modeled after state-level reforms in Texas. According to his press release on the topic, here's a summary of what the bill would do:

• Requires the Department of Justice to use existing funds to develop and implement recidivism reduction programming (drug rehabilitation, education, skills training, work programs, etc.) for 100% of eligible federal prisoners within 5 years. Ineligible prisoners include violent offenders, sex offenders, terrorists, child abusers, human traffickers, and repeat federal offenders.See the full text here. Haven't read the full thing myself, yet, so Grits may have more to say later on the topic, particularly if the legislation gains traction. Presently, Cornyn has three co-sponsors - Republican Senators Chuck Grassley, Orrin Hatch, and Mike Lee - and the bill has been referred to the Senate Judiciary Committee. Sounds good from the summary, but I'd feel more sanguine about its chances if the bill had bipartisan sponsorship - a key factor in passing Texas' 2007 reforms - and/or there was companion legislation in the House.

• Requires the Attorney General to enter into partnership with non-profit and faith-based organizations to provide many of these programs at little or no cost to the taxpayer.

• Requires the use of existing resources to develop a federal post-conviction risk assessment tool that uses empirical data to classify all federal prisoners as (1) low-risk of recidivism; (2) medium risk of recidivism; or (3) high risk of recidivism, and allow for regular reassessments of each eligible prisoner over time.

• Allows prisoners who are classified as low-risk to earn up to 50% of their remaining sentence in home confinement or a halfway house, with earned time credit accruing at a rate of 30 days for every 30 days the prisoner is successfully completing recidivism reduction programming.

• Allows medium-risk and high-risk prisoners to earn time credits at a rate of 30% and 20% while they are successfully completing recidivism reduction programming, but does not allow them to cash in this credit until the risk assessment tool shows that they are a low-risk of recidivating.

• Reduces the need for new federal prison construction allocation by working to cap and reduce the number of incarcerated offenders by shifting prisoners near the end of their sentence to home confinement.

Friday, September 13, 2013

Probation revocations down, but not by much; re-arrest rates among DWI probationers plummets

More evidence that Texas' 2007 probation reforms perhaps contributed less than has been previously estimated to recent prison population declines. The main strategy of the 2007 reforms was to reduce probation and parole revocations to prison by incentivizing diversion and progressive sanctions programs. That's worked better on the parole side than for probation (aka "community supervision"). From the Dec. 2012 "Report to the Governor and Legislative Budget Board on the Monitoring of Community Supervision Diversion Funds" (pdf):

County-level probation revocation trends

By contrast, reducing probation revocations has been a tougher nut to crack, in part because of decentralized local control over the process among various counties and judges. Here are the relative increases and decreases for probation revocations among Texas' largest departments since just before Texas' much-vaunted probation reforms took effect:

This chart perhaps provides a better sense of relative county practices than the previous one. It compares probation populations and revocations among large counties as a proportion of their statewide total. (See this data for all counties in Appendix C to the report.) Counties in which the right-side number is significantly greater than the left-hand column may be considered more aggressive at revoking probationers than their peers. That differential is especially significant in massive Harris County because of the sheer volume they process. Tarrant's numbers here are especially striking, putting their paltry 4.3% decline from the earlier chart in context. Meanwhile, Travis, Hidalgo, and even Bexar don't appear nearly as problematic on this chart as they did in the first table.

Recidivism among probationers declining, especially DWI

According to the Dec. 2012 report, 71.7% of felony probationers revoked back to prison in FY2012 were convicted of nonviolent crimes - drug offenses (32.2%), property offenses (30.4%), and DWI (9.1%), with the rest coming from violent (17.9%) and other (10.4%) felony offenses.

Remarkably, and for the most part unheralded, recidivism rates for felony probationers have been declining. "The overall two-year re-arrest rate for the FY2005 sample was 34.4% (8,914 offenders). The overall two-year re-arrest rate for the FY2010 sample was 31.8% (8,811 offenders), which was a decrease from the FY2005 sample."

The drop in re-arrest rates for DWI offenders in those two studies was especially striking: 16.9% of the 2005 cohort was re-arrested compared to 11.5% of the 2010 cohort - a 32% drop! That's a success story nobody tells much. Re-arrest rates for probationers convicted of drug offenses declined 13% over this period; 10.6% for property offenders. But DWI stands out. Perhaps new treatment resources aimed at that group are helping.

Felony revocations to TDCJ in FY2012 represent a 2.8% decrease from FY2005 (677 fewer felony revocations) and a 1.8% decrease from FY2011 (432 fewer felony revocations). However, the percentage of revocations to TDCJ for a technical violation of community supervision conditions increased from 48.5% in FY2011 to 49.0% in FY2012.Those are essentially insignificant reductions given the scope of the decline in state prison populations witnessed over the last half decade.* Felony technical revocations among probationers declined 10.9% from 2005 to 2012, TDCJ reported, but they're still awfully high and that small decline was far out-paced by two factors on the parole side: Dramatically reduced parole revocations and marginally increased approval rates by the parole board. Both may be viewed as an expression of legislative policy. Reduced parole revocations stem from greater use of intermediate sanctions facilities (ISFs) and other diversion programs created after 2007. And higher approval rates, particularly for low-risk offenders, resulted in large part from the board finally edging closer to targets under non-binding release guidelines that the Lege mandated they create.

County-level probation revocation trends

By contrast, reducing probation revocations has been a tougher nut to crack, in part because of decentralized local control over the process among various counties and judges. Here are the relative increases and decreases for probation revocations among Texas' largest departments since just before Texas' much-vaunted probation reforms took effect:

Change in Felony Revocations to

TDCJ among largest counties, 2005-2012

| CSCD | Percent change in revocations |

| Dallas | -22.8% |

| Harris | -17.8% |

| Bexar | 94.0% |

| Tarrant | -4.3% |

| Hidalgo | -5.3% |

| El Paso | -39.6% |

| Travis | 32.1% |

| Cameron | 22.4% |

| Nueces | 1.8% |

**See note below on Collin Co.

.

Travis County's increase in revocations surprised me given their department's reputation for reliance on progressive sanctions, etc.. Cameron County attributes their increase to "more aggressive absconder apprehension and increased monitoring of compliance with community supervision conditions." Otherwise, Bexar County is the most prominent, chronic outlier among large counties, as has been the case since these reports began coming out.

2012 probation revocations compared

to supervised population, large counties

| CSCD | % 2012 statewide probation pop | % 2012 statewide felony revocations |

| Dallas | 13.6% | 10.5% |

| Harris | 11.5% | 12.4% |

| Bexar | 6.7% | 6.8% |

| Tarrant | 4.9% | 7.1% |

| Hidalgo | 4.0% | 2.8% |

| El Paso | 3.7% | 1.5% |

| Travis | 3.4% | 3.0% |

| Cameron | 2.3% | 1.9% |

| Nueces | 1.7% | 2.2% |

| Collin | 1.7% | 1.9% |

Recidivism among probationers declining, especially DWI

According to the Dec. 2012 report, 71.7% of felony probationers revoked back to prison in FY2012 were convicted of nonviolent crimes - drug offenses (32.2%), property offenses (30.4%), and DWI (9.1%), with the rest coming from violent (17.9%) and other (10.4%) felony offenses.

Remarkably, and for the most part unheralded, recidivism rates for felony probationers have been declining. "The overall two-year re-arrest rate for the FY2005 sample was 34.4% (8,914 offenders). The overall two-year re-arrest rate for the FY2010 sample was 31.8% (8,811 offenders), which was a decrease from the FY2005 sample."

The drop in re-arrest rates for DWI offenders in those two studies was especially striking: 16.9% of the 2005 cohort was re-arrested compared to 11.5% of the 2010 cohort - a 32% drop! That's a success story nobody tells much. Re-arrest rates for probationers convicted of drug offenses declined 13% over this period; 10.6% for property offenders. But DWI stands out. Perhaps new treatment resources aimed at that group are helping.

Wednesday, January 16, 2013

Southern states pushing de-incarceration envelope

Recent legislation in other southern states offer possibilities for sentencing reform that perhaps could be replicated by the 83rd Texas Legislature if they can muster the will to reduce corrections spending. In South Carolina, reported The State, the Department of Probation, Parole and Pardon Services was previously "focused on punishing offenders who did not follow the

rules. Sentencing reform forced the department to reward offenders who

did follow the rules. Now, offenders can reduce their supervision by 20

days for every month that they follow the rules. A shorter sentence

means the offender pays less money in supervision fees. In some cases,

he or she even earns a refund."

The Palmetto State reforms also focused on risk assessment and better matching of services to risks:

Meanwhile, via this AP story I learned of Georgia's Special Council on Criminal Justice Reform, which produced this report (pdf) suggesting various de-incarceration initiatives. According to AP, "There are new penalty provisions for certain crimes, and the elements of other crimes have changed so that some that used to be felonies are now misdemeanors." The Peach State also reduced the level of supervision for successful probationers: "Probationers are put on an administrative caseload after two years, and the council's report says only 18 percent of those unsupervised probationers are rearrested, as opposed to 60 percent of active probationers."

Read more here: http://www.thestate.com/2013/01/13/2587969/how-sentencing-reform-is-saving.html#storylink=c

Read more here: http://www.thestate.com/2013/01/13/2587969/how-sentencing-reform-is-saving.html#storylink=cpy

The Palmetto State reforms also focused on risk assessment and better matching of services to risks:

The probation department now assesses all offenders to determine their risk for reoffending. If an offender has no family support, the department will try to get that person involved in a church, if they are religious, or in some other support group for encouragement.The changes in South Carolina have already shifted the mix of prisoners incarcerated in the state:

In Spartanburg County, probation officers doubled the rate of youthful offenders completing probation successfully just by assigning each one a counselor, according to Jeff Harmon, the agency’s Spartanburg agent in charge.

The department still punishes offenders. But prison is now the last option.

Now, if offenders break the rules, they could have to pick up trash on the highway, report to their probation officers more frequently or spend a weekend in jail – what Department of Corrections director Bill Byars refers to as “a refresher course.”

“Frankly, we have had to relearn the business of probation and parole,” said Kela E. Thomas, the probation department’s director.

It appears to be working.

In 2012, the agency revoked the probations of 3,323 former inmates – 1,461 fewer than in 2010.

Before sentencing reform, the prison population was spilt about 50-50 between violent and nonviolent inmates. Today, 62 percent of inmates are incarcerated for violent offenses, said John Carmichael, the Corrections Department’s deputy director for programs and services.In Texas, offenders convicted of violent offenses make up 55% of inmates, compared to 62% in post-reform South Carolina.

That shift has allowed the department to focus more of its resources on its most dangerous inmates.