Showing posts with label Bexar County. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Bexar County. Show all posts

Wednesday, January 29, 2020

Bail reform saves lives, "The Ogg Blog," pay-per-surveillance, and other stories

Here are a few odds and ends that merit Grits readers' attention:

Kim Ogg oppo blog launched

The Justice Collaborative has launched The Ogg Blog, providing background on various criticisms vs. embattled Harris County DA Kim Ogg as she faces a bevy of opponents in the coming March primary. Grits is grateful; I'd intended to compile a long, greatest-hits post for Ogg as a bookend to this one about Travis County DA Margaret Moore, so they've saved me the trouble.

Bexar County Jail deaths argue for bail reform

At the Texas Observer, Michael Barajas examines recent deaths in the Bexar County Jail, a topic which led the Express-News recently to call for an audit. At root, the problems implicate a broken bail system that incarcerates low-risk defendants because they don't have money: "Don’t lose sight of the broad strokes," admonished the Express-News. "Three defendants in their 60s. All charged with criminal trespass. All given nominal cash bonds that kept them incarcerated pretrial. All dead in our jail. All of this in the span of about a year." But local judges, including one who ran a bail-bond company before ascending to the bench, have consistently opposed any move toward reforming bail processes.

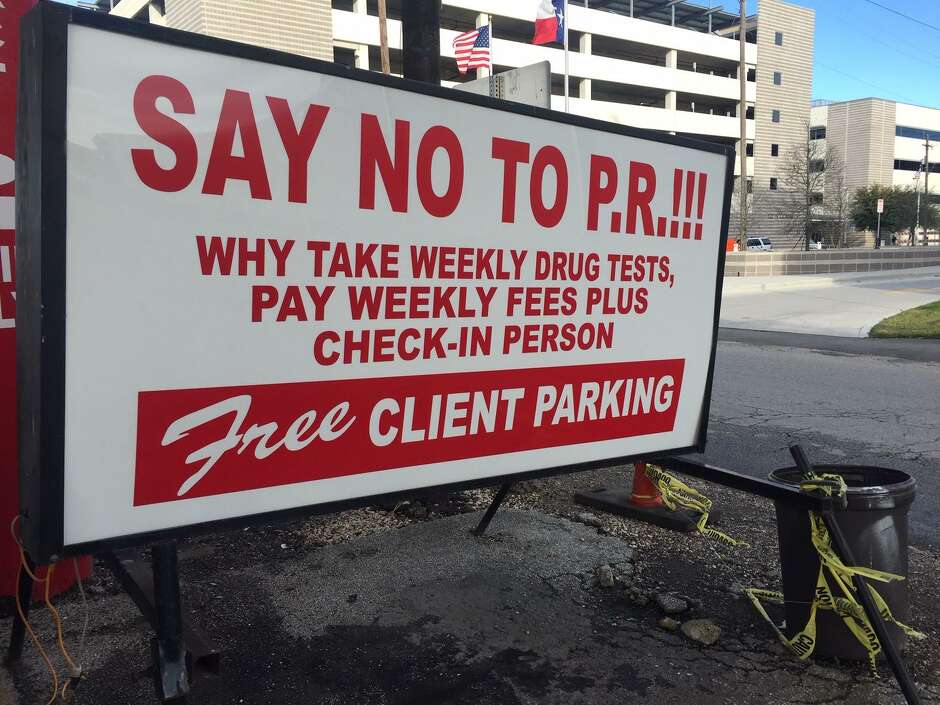

To be clear, despite plaintive cries that bail reform will harm public safety, the real reason bail-bond companies oppose reform is all about preserving their anachronistic business model. Continuing to subsidize this industry in the 21st century is akin to subsidizing buggy whip manufacturers in the 20th: Their time has passed.

Fact checking the Governor on homeless policies

PolitiFact fact-checked Governor Greg Abbott on his claims about Austin's homeless. Guess how he fared?

Levin on reducing Big-D murder rate

Marc Levin from Right on Crime appeared on the Point of View podcast to discuss Dallas' plan to reduce its murder rate.

Pay-to-surveil

Google wants to begin charging law enforcement for requests for location information and other user data. The big telecoms already do so.

Kim Ogg oppo blog launched

The Justice Collaborative has launched The Ogg Blog, providing background on various criticisms vs. embattled Harris County DA Kim Ogg as she faces a bevy of opponents in the coming March primary. Grits is grateful; I'd intended to compile a long, greatest-hits post for Ogg as a bookend to this one about Travis County DA Margaret Moore, so they've saved me the trouble.

Bexar County Jail deaths argue for bail reform

At the Texas Observer, Michael Barajas examines recent deaths in the Bexar County Jail, a topic which led the Express-News recently to call for an audit. At root, the problems implicate a broken bail system that incarcerates low-risk defendants because they don't have money: "Don’t lose sight of the broad strokes," admonished the Express-News. "Three defendants in their 60s. All charged with criminal trespass. All given nominal cash bonds that kept them incarcerated pretrial. All dead in our jail. All of this in the span of about a year." But local judges, including one who ran a bail-bond company before ascending to the bench, have consistently opposed any move toward reforming bail processes.

To be clear, despite plaintive cries that bail reform will harm public safety, the real reason bail-bond companies oppose reform is all about preserving their anachronistic business model. Continuing to subsidize this industry in the 21st century is akin to subsidizing buggy whip manufacturers in the 20th: Their time has passed.

Fact checking the Governor on homeless policies

PolitiFact fact-checked Governor Greg Abbott on his claims about Austin's homeless. Guess how he fared?

Levin on reducing Big-D murder rate

Marc Levin from Right on Crime appeared on the Point of View podcast to discuss Dallas' plan to reduce its murder rate.

Pay-to-surveil

Google wants to begin charging law enforcement for requests for location information and other user data. The big telecoms already do so.

Friday, October 25, 2019

The state of 'progressive prosecutors' in Texas

The article in The Atlantic titled "Texas prosecutor fights for reform" has a certain "Man Bites Dog" quality, which I suppose makes local news from Texas interesting enough for East and West coast media and muckety mucks to take notice. Not that John Creuzot's work in Dallas doesn't deserve attention. In Grits' view, he is the most confident, competent, and sure-footed of Texas' new crop of Democratic DAs. But at this point, the term "progressive district attorney" requires so many caveats that it should probably be discarded, at least in red states, until a few key benchmarks have been established and met.

When Kim Ogg of Houston, Mark Gonzalez in Corpus Christi, and Margaret Moore in Austin were elected DAs of their respective counties in 2016, there was a clutch of mostly national advocates and journalists, coupled with a few local electoral partisans, who pronounced them part of a new wave of "progressive prosecutors." Grits argued at the time that there was no such thing (and still largely thinks that's true).

Larry Krasner's election in Philadelphia changed things. His office produced a memo detailing new policies aimed at reducing incarceration rates that was much more daring and aggressively decarceral than any previous US prosecutor had ever suggested. (For a contemporary podcast discussion of Krasner's memo in context of Texas candidates, see here.) Soon, prosecutors in other states began running mimicking parts of Krasner's approach as well as expanding or exploring other decarceral programs.

In Texas, though, the decarceral efforts of our Democratic DAs have been much more modest.

Harris and Travis Counties have created special courts for state-jail felonies that have helped chip away at state-jail incarceration rates. Joe Gonzalez in San Antonio took a won't-prosecute stance on low-level pot possession (Ogg created a pretrial diversion program for pot.) And both Mark Gonzalez and Margaret Moore found themselves in the happy position to replace such embarrassingly bad prosecutors, they could look like an improvement just by avoiding overt misconduct and not drooling on themselves in public.

On bail reform, in particular, for the most part these prosecutors' positions are far from "progressive." And even if they are, as with Creuzot, judges, local criminal-defense attorneys, and other special interests have proven effective at throwing a monkey wrench into potential solutions.

Ogg in particular has chosen to pick fights with county commissioners, newly elected Democratic judges, reformers, journalists, and academics over every perceived slight, leaving herself ever-more frustrated and isolated. Most prominently, she attacked the pending bail-reform settlement and demanded the county radically increase her staff size without acknowledging how that would a) create disadvantages for underfunded indigent defense or b) run counter to decarceration goals. (Recently a group of scholars came out to criticize the methodology of a study her office promoted to justify the request for more staff.)

Creuzot was the first Texas DA to more comprehensively articulate his own decarceral agenda, sort of a Larry-Krasner-Lite, but whose pronouncements are peppered with "y'alls." His policies were more modest than, say, newly elected prosecutors in Philly, St. Louis, or Boston. Even so, there's no doubt Creuzot's positions were more concrete and his thinking about decarceration is the most-well-developed of any Lone-Star prosecutor. Indeed, his general election vs. a Republican incumbent essentially centered around which one of them would be more reform-minded.

By contrast, in Houston, some of the same reform voices who prematurely hailed Kim Ogg as a progressive in 2016 are calling for her replacement by Audia Jones. Margaret Moore last year asked local reformers to endorse her push to merge the District and County Attorney offices under her control, but refused to enact any of the reforms local advocates wanted in return. As a result, the merger didn't happen and she now faces a serious reform challenger in Jose Garza.

Going forward, if any of these insurgents win in the coming Democratic primaries, then the terrain will have shifted and "progressive" will no longer effectively serve as a synonym for "Democrat" in Texas when it comes to prosecutor elections, as seems to have been the case so far.

When Kim Ogg of Houston, Mark Gonzalez in Corpus Christi, and Margaret Moore in Austin were elected DAs of their respective counties in 2016, there was a clutch of mostly national advocates and journalists, coupled with a few local electoral partisans, who pronounced them part of a new wave of "progressive prosecutors." Grits argued at the time that there was no such thing (and still largely thinks that's true).

Larry Krasner's election in Philadelphia changed things. His office produced a memo detailing new policies aimed at reducing incarceration rates that was much more daring and aggressively decarceral than any previous US prosecutor had ever suggested. (For a contemporary podcast discussion of Krasner's memo in context of Texas candidates, see here.) Soon, prosecutors in other states began running mimicking parts of Krasner's approach as well as expanding or exploring other decarceral programs.

In Texas, though, the decarceral efforts of our Democratic DAs have been much more modest.

Harris and Travis Counties have created special courts for state-jail felonies that have helped chip away at state-jail incarceration rates. Joe Gonzalez in San Antonio took a won't-prosecute stance on low-level pot possession (Ogg created a pretrial diversion program for pot.) And both Mark Gonzalez and Margaret Moore found themselves in the happy position to replace such embarrassingly bad prosecutors, they could look like an improvement just by avoiding overt misconduct and not drooling on themselves in public.

On bail reform, in particular, for the most part these prosecutors' positions are far from "progressive." And even if they are, as with Creuzot, judges, local criminal-defense attorneys, and other special interests have proven effective at throwing a monkey wrench into potential solutions.

Ogg in particular has chosen to pick fights with county commissioners, newly elected Democratic judges, reformers, journalists, and academics over every perceived slight, leaving herself ever-more frustrated and isolated. Most prominently, she attacked the pending bail-reform settlement and demanded the county radically increase her staff size without acknowledging how that would a) create disadvantages for underfunded indigent defense or b) run counter to decarceration goals. (Recently a group of scholars came out to criticize the methodology of a study her office promoted to justify the request for more staff.)

Creuzot was the first Texas DA to more comprehensively articulate his own decarceral agenda, sort of a Larry-Krasner-Lite, but whose pronouncements are peppered with "y'alls." His policies were more modest than, say, newly elected prosecutors in Philly, St. Louis, or Boston. Even so, there's no doubt Creuzot's positions were more concrete and his thinking about decarceration is the most-well-developed of any Lone-Star prosecutor. Indeed, his general election vs. a Republican incumbent essentially centered around which one of them would be more reform-minded.

By contrast, in Houston, some of the same reform voices who prematurely hailed Kim Ogg as a progressive in 2016 are calling for her replacement by Audia Jones. Margaret Moore last year asked local reformers to endorse her push to merge the District and County Attorney offices under her control, but refused to enact any of the reforms local advocates wanted in return. As a result, the merger didn't happen and she now faces a serious reform challenger in Jose Garza.

Going forward, if any of these insurgents win in the coming Democratic primaries, then the terrain will have shifted and "progressive" will no longer effectively serve as a synonym for "Democrat" in Texas when it comes to prosecutor elections, as seems to have been the case so far.

Wednesday, August 21, 2019

Bexar County to give Narcan to addicts exiting jail, but many still won't call 911 for fear of felony arrest

Addicts leaving the county jail in San Antonio will now receive a dose of Narcan in case they overdose, the Express News reported. Overdoses are more common after incarceration because addicts may have lost some of their tolerance. That can cause people to overdose when they use the same amounts they used before. Funding for the program came from a federal grant.

Of course, folks can still be arrested for drug possession if they call 911 to report an overdose. A Bexar Sheriff's deputy told the paper that:

In 2018, the Austin Statesman reported that, "similar laws in other states have resulted in as much as a 15 percent drop in opioid overdoses in the past five years, despite nationwide increases. The laws also do not appear to increase the number of drug users, the data shows."

That's shaping up as one of the worst and most destructive vetoes of Abbott's tenure so far.

Of course, folks can still be arrested for drug possession if they call 911 to report an overdose. A Bexar Sheriff's deputy told the paper that:

people shouldn’t be concerned about contacting authorities should a friend or family member overdose.

“That’s the least of your worries at that point, ending up in jail,” he said. “You should be worried about surviving, or about leaving your child without a mother or father.”That's easy to say, but it would mean more if Gov. Greg Abbott hadn't vetoed Good Samaritan legislation in 2015 that would have prevented 911-callers from being arrested for calling in an overdose.

In 2018, the Austin Statesman reported that, "similar laws in other states have resulted in as much as a 15 percent drop in opioid overdoses in the past five years, despite nationwide increases. The laws also do not appear to increase the number of drug users, the data shows."

That's shaping up as one of the worst and most destructive vetoes of Abbott's tenure so far.

Labels:

Bexar County,

County jails,

Harm Reduction,

overdoses

Sunday, June 30, 2019

Judge abused discretion, violated due-process rights, by revoking probation w/o a hearing: Will he be sanctioned?

A misdemeanor DWI case out of San Antonio deserves broader attention, with interesting and important implications on several levels.

Wayne Christian - a Republican county-court-at-law judge in Bexar County first elected in 1996, who ran unopposed in the 2018 election - has routinely inserted himself on behalf of the state in lieu of county prosecutors in probation revocation cases, often refusing to allow testimony and deciding them with no evidence. But thanks to appellant Allison Jacobs, her attorneys, and perhaps most interestingly, new Bexar DA Joe Gonzalez, that practice will now be revisited.

According to columnist Josh Brodesky of the SA Express News, Judge Christian's court "leads all County Court-at-Law judges in what’s known as MTRs - motions to revoke probation. He also leads other judges in jail bed days."

In Jacobs' case, she'd been a model probationer but failed three urinalysis tests toward the end of her 14-month probation period. Her attorney wanted to argue that this was a false positive caused by a diet pill she'd been taking, which long-time readers know is not an implausible scenario, particularly in Bexar County.

But Judge Christian refused to hold a hearing and based his decision to revoke on a brief conversation with the court liaison from the probation department. This violated Jacobs' due process rights, which should have entitled her to challenge evidence against her in a hearing before she's revoked to jail. But Christian went even further. Reported Brodesky:

And it wasn't an isolated incident. Again from Brodesky: “There have been situations where our prosecutors have been placed in positions where they are not in agreement with going forward on a motion to revoke,” District Attorney Joe Gonzales said. “And they have made the decision to not sign off on the motions, and the judge has moved on them on his own.”

Let's delve into the secondary issue of denying the defendant bail while her appeal was litigated. The actions attributed to Judge Christian, who went out of his way to thwart the decision of a district judge in a habeas corpus writ, seem like extraordinary measures for a judge to take. The brief from Jacobs' attorney includes a footnote - which the DA's office corroborated (more on this later) - describing the remarkable sequence of events in more detail (citations to the record omitted):

All of this is remarkable, and more than a bit concerning. Judge Christian seems intent on ignoring the mandates of his job and substituting his own judgments for the process. In doing so, he's also increasing incarceration - keep in mind he has the highest numbers of all Bexar-county-court-at-law judges on both revocations and resulting jail-bed days.

Finally, Grits was interested in the Express-News' analysis that Christian leads all other Bexar judges in motions to revoke. How do we know? That's something tracked in state-level court data, but totals are only available in Office of Court Administration queries at the county-wide level.

So, to summarize, here are the implications and questions Grits would take away from this episode (feel free to suggest more in the comments):

|

| Here's Judge Christian dressed in a camo robe. (source) |

In Jacobs' case, she'd been a model probationer but failed three urinalysis tests toward the end of her 14-month probation period. Her attorney wanted to argue that this was a false positive caused by a diet pill she'd been taking, which long-time readers know is not an implausible scenario, particularly in Bexar County.

But Judge Christian refused to hold a hearing and based his decision to revoke on a brief conversation with the court liaison from the probation department. This violated Jacobs' due process rights, which should have entitled her to challenge evidence against her in a hearing before she's revoked to jail. But Christian went even further. Reported Brodesky:

Not only did Christian sentence her [to jail], but court records show he also denied her appeal for reasonable bail. He then modified a district court judge’s order of bail for $1,600 to make conditions more onerous. Another district judge lessened those conditions, and when Jacobs was finally released from the Bexar County Adult Detention Center in November, Christian responded.

According to court filings: Upon release on bail, Jacobs was scheduled for a pretrial services orientation on Nov. 19, 2018. But Christian called pretrial services and had the orientation changed to Nov. 13, 2018. Pretrial services was unable to notify her about this change, so she missed the orientation. The next day Christian revoked her bail, issuing a warrant for an arrest.

What gives? This is a defendant who was two weeks away from completing 14 months of probation for a serious, but misdemeanor charge.

[Jacobs' attorney Jodi] Soyars said she likes Christian personally, and, obviously, has concerns about crossing him. She has other cases in his court. But she viewed this as representative of a broader issue and unfair to her client.

“He routinely denies defendants the right to due process,” she said.So the judge routinely disallows prosecutors from participating in revocation decisions, acting himself on behalf of the state. And he doesn't allow a defendant to present evidence of possible actual innocence, simply declaring the allegations "true" by fiat without, as Soyars said in her brief, a "scintilla of evidence."

And it wasn't an isolated incident. Again from Brodesky: “There have been situations where our prosecutors have been placed in positions where they are not in agreement with going forward on a motion to revoke,” District Attorney Joe Gonzales said. “And they have made the decision to not sign off on the motions, and the judge has moved on them on his own.”

Let's delve into the secondary issue of denying the defendant bail while her appeal was litigated. The actions attributed to Judge Christian, who went out of his way to thwart the decision of a district judge in a habeas corpus writ, seem like extraordinary measures for a judge to take. The brief from Jacobs' attorney includes a footnote - which the DA's office corroborated (more on this later) - describing the remarkable sequence of events in more detail (citations to the record omitted):

While the appeal and motion for new trial procedures were taking place, some additional procedural issues arose and were dealt with, which are evident in the clerk’s record. A brief explanation to make sense of the clerk’s record follows: After a Notice of Appeal was filed, a Motion for Reasonable Bail Pending Appeal was also filed. . This is a misdemeanor case and bail was required to be granted. Judge Wayne Christian denied bail. An Application for Writ of Habeas Corpus Seeking Setting of Reasonable Bail was then filed and heard by District Court Judge Melisa Skinner in the 290th District Court. Judge Skinner granted the Writ and ordered bail of $1,600 and SCRAM as a condition. . The same day, Judge Christian called his clerk and added full GPS, daily reporting, and daily UAs as conditions of release, effectively changing the order of a District Court judge. A second Application for Writ of Habeas Corpus was then filed, requesting reasonable release conditions. Judge Joey Contreras in the 187th District Court set this Writ for a hearing on October 17, 2018. At the hearing, Judge Contreras granted reasonable conditions. After several weeks passed with Jacobs unable to meet the bail requirements, Judge Contreras amended his bond order to allow Jacobs a way to be released pending the appeal. Jacobs was released from jail and given an orientation date of November 19, 2018 to report to pre-trial services. On November 13, 2018, Judge Christian called pre-trial services and ordered pre-trial services to require Jacobs to report on that date. Pre-trial services was unable to contact Jacobs and Jacobs had not yet had her orientation that would put her under the requirements of pre-trial supervision. Judge Christian then required pre-trial services to send over a violation report on November 14, 2018, whereupon Judge Christian revoked her bail and issued a warrant. Judge Contreras again intervened and reinstated Jacobs’ bail on November 16, 2018.This conduct to my mind, deserves public censure if not ouster by the State Commission on Judicial Conduct. And indeed, in its opinion, the 4th Court of Appeals called Christian's actions an example of "an unsuitable practice by a county court at law judge."

All of this is remarkable, and more than a bit concerning. Judge Christian seems intent on ignoring the mandates of his job and substituting his own judgments for the process. In doing so, he's also increasing incarceration - keep in mind he has the highest numbers of all Bexar-county-court-at-law judges on both revocations and resulting jail-bed days.

But perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the case was the fact that District Attorney Joe Gonzales joined with defense counsel to dispute Christian's "unsuitable" practices, which apparently had been tolerated by his predecessors without contest for many years.

One aspect of electing reform-minded prosecutors Grits had not fully considered (or perhaps more accurately, had not dared dream possible) is that they could challenge unconstitutional court practices from the inside, or join those challenges, as happened here. So kudos to Gonzalez for his stance here, that's a big deal!

Prosecutors' role should be to "seek justice." But too often, they see themselves as on a side, and it's the opposite side from the defendant. So when the judge plays prosecutor as well, as is the practice in Judge Christian's court, defendants without means to pay a phalanx of private lawyers have little chance.

Finally, Grits was interested in the Express-News' analysis that Christian leads all other Bexar judges in motions to revoke. How do we know? That's something tracked in state-level court data, but totals are only available in Office of Court Administration queries at the county-wide level.

Grits doesn't immediately know the data source from which Brodesky identified the number of probation revocations by court. (If any readers know how to access this data from public sources, please let us know in the comments.) But that's a useful figure because, as regular readers are aware, probation revocations are a significant cause of Texas prison admissions, and revoked misdemeanor probationers go to county jail, contributing to local costs.

So, to summarize, here are the implications and questions Grits would take away from this episode (feel free to suggest more in the comments):

- A judge for years felt free to ignore his duties to hold probation-revocation hearings and neither local defense attorneys nor the DA's office called him on it. Is this happening elsewhere?

- Will the State Commission on Judicial Conduct sanction Judge Christian?

- Does this flagrant disregard for judicial duties rise to the level of the state bar challenging Christian's licensure?

- Will media in other jurisdictions begin analyzing which judges have the most probation revocations and hold them accountable for successes/abuses?

- An under-examined aspect of evaluating "progressive" prosecutors will be how they respond to appeals challenging unconstitutional practices and other reform litigation. People have discussed this in the context of bail reform, but Jacobs case shows there are potentially many more areas where this could become important.

Labels:

Bexar County,

DWI,

Judicial Conduct Commission,

Judiciary,

misdemeanors,

Probation

Tuesday, February 19, 2019

TX bail-reform momentum growing amidst supportive press

|

| Source: SA Express-News |

Here are several items anyone tracking the Texas bail debate will want to have read:

- SA Express-News: Bexar's stunning embrace of cash bail

- Austin Statesman: Texas' bail bond system is broken. This bill can help fix it

- Beaumont Enterprise: State should reform cash bail system

- Filter: New evidence backs calls to end cash bail

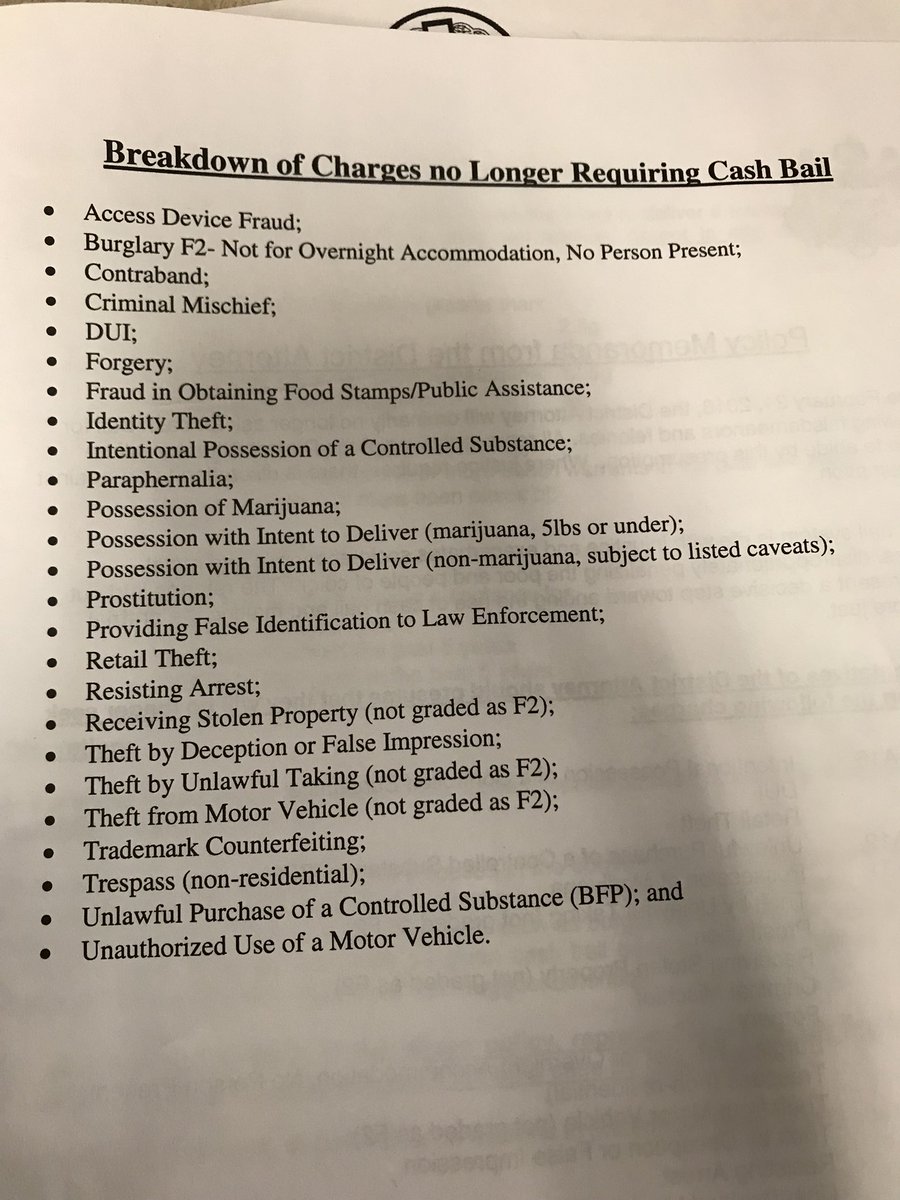

The Filter story describes Philadelphia DA Larry Krasner's bail reform efforts. Here is the list of offenses for which his office no longer requests cash bail:

RELATED: On the January episode of our Reasonably Suspicious podcast, my co-host Mandy Marzullo and I discussed the various federal bail-reform lawsuits around the state. It's the top story, starting at the 1:58 mark.

Labels:

bail,

Bexar County,

County jails,

pretrial detention

Tuesday, August 16, 2016

On the limits of enacting police reform through union contracts

San Antonio Mayor Ivy Taylor went to the meet-and-confer negotiating table this spring with seven requests related to police accountability, reported the Express-News (8/15). A city council member labeled two of the reforms "critical."

Police union contracts have been targeted by the Black Lives Matter movement as a potential vehicle for improved accountability. However, this episode shows the limits of attempting to effect police reform in Texas through meet-and-confer negotiations, which in practice give the local police union veto power over any and all changes.

That said, there is more than one way to skin a cat. Austin had similarly witnessed officers frequently having their terminations overturned by an arbitrator until the department finally adopted a change for which local advocates had pushed for more than a decade: Creation of a disciplinary matrix in the APD policy manual which specifies punishment ranges for significant misconduct.

Arbitrators frequently overturn police officers' firings on the grounds that other, similarly situated officers were not punished in the same fashion. But a disciplinary matrix creates a range of prescribed punishments which arbitrators may presume to be reasonable.

The ability to make firings stick is a key part of confronting what's been called "a departmental culture which protects its own and is unwelcoming of supervision" in San Antonio. Keeping police misconduct on the record when the department makes personnel and promotion decisions helps keep bad apples from remaining on the force or even entering management just because they've hung around for a long time.

These are modest reforms at best but even they were too much for the union and the city didn't go to the mat on the issue the way they did on the Evergreen Clause. Certainly there was no effort to tie wage and benefit hikes to the union's acceptance of a (slightly) stronger disciplinary process.

It's possible the Mayor could have gotten more if there was significant community organizing backing her effort. As things stand, the public didn't know about her police accountability proposals until after they'd been rejected. Rallying the public in support of her proposals would have boosted the likelihood of success. Even so, I'm glad to see her making an effort when no one's looking. If she's serious about the topic, she'll find other opportunities to address it going forward.

A police chief “needs to be able to rely on prior discipline to determine punishment,” the first request read, “so it may be presented to show progressive discipline in arbitrations.”But the union "flatly refused to entertain the requests for reform" and so none of them got in.

When an officer appeals his or her punishment, it triggers an arbitration process that proceeds like a trial. And arbitrators often reduce punishments; in the past seven years, they overturned or reduced five of 13 disciplinary rulings on appeal. All five were terminations, according to city officials.

The current contract limits how far back a police chief can invoke prior misconduct in arbitration: 10 years for drug and alcohol-related issues, five years for acts of “intentional violence” and just two years for all other misconduct.

“An entire officer’s discipline record should be allowable,” the request concluded.

The second reform: “Remove Requirement to Reduce Agreed Short Suspensions to Reprimands.”

Currently, suspensions of three days or less are automatically reduced to written reprimands after two years — a mechanism that [one city council member] says has amounted to “altering” police records.

“Suspensions need to remain on the record to accurately report an officer’s history and show progressive discipline in arbitration,” the city’s request to the union stated.

Police union contracts have been targeted by the Black Lives Matter movement as a potential vehicle for improved accountability. However, this episode shows the limits of attempting to effect police reform in Texas through meet-and-confer negotiations, which in practice give the local police union veto power over any and all changes.

That said, there is more than one way to skin a cat. Austin had similarly witnessed officers frequently having their terminations overturned by an arbitrator until the department finally adopted a change for which local advocates had pushed for more than a decade: Creation of a disciplinary matrix in the APD policy manual which specifies punishment ranges for significant misconduct.

Arbitrators frequently overturn police officers' firings on the grounds that other, similarly situated officers were not punished in the same fashion. But a disciplinary matrix creates a range of prescribed punishments which arbitrators may presume to be reasonable.

The ability to make firings stick is a key part of confronting what's been called "a departmental culture which protects its own and is unwelcoming of supervision" in San Antonio. Keeping police misconduct on the record when the department makes personnel and promotion decisions helps keep bad apples from remaining on the force or even entering management just because they've hung around for a long time.

These are modest reforms at best but even they were too much for the union and the city didn't go to the mat on the issue the way they did on the Evergreen Clause. Certainly there was no effort to tie wage and benefit hikes to the union's acceptance of a (slightly) stronger disciplinary process.

It's possible the Mayor could have gotten more if there was significant community organizing backing her effort. As things stand, the public didn't know about her police accountability proposals until after they'd been rejected. Rallying the public in support of her proposals would have boosted the likelihood of success. Even so, I'm glad to see her making an effort when no one's looking. If she's serious about the topic, she'll find other opportunities to address it going forward.

Labels:

Bexar County,

civil service code,

meet and confer,

unions

Wednesday, June 15, 2016

No prosecution for SA cop who assaulted DWI suspect

Grits sent off an open record request this morning to the San Antonio PD about this case in which, "A veteran San Antonio Police officer was suspended 30 days earlier this

year after he admitted to punching a drunk driving suspect eight times

in the head while trying to get him to comply with a blood draw." Notably, "The district attorney's office declined to pursue a charge against [the suspect] for resisting arrest." If there turns out to be footage, perhaps I'll compile another short web video.

One wonders, beyond the thirty-day suspension from his job - which Zimmerman covered using "accrued holiday time," so he really never missed a day - why this officer wasn't subjected to criminal charges for assaulting the suspect, just as you or I would be if we hit someone in the head eight times in the central magistrate's office at the jail.?

See related, recent Grits posts:

One wonders, beyond the thirty-day suspension from his job - which Zimmerman covered using "accrued holiday time," so he really never missed a day - why this officer wasn't subjected to criminal charges for assaulting the suspect, just as you or I would be if we hit someone in the head eight times in the central magistrate's office at the jail.?

See related, recent Grits posts:

Labels:

Bexar County

Saturday, June 04, 2016

SAPD use of force rate increasing

Just as the Texas Lege recognized last session that there needed to be greater transparency surrounding police-involved shootings, use of force reports have long been a murky backwater of seldom-disclosed information that the public seldom sees. In the SA Express News, John Tedesco had a lengthy, anecdote-filled feature on May 28 titled, "Analysis: SAPD officers use force at higher rates against minorities" in which he delved into those reports in SA in great detail Here are some statistical highlights:

Tedesco does inform us that, "The San Antonio Police Department has compiled thousands of “use of force” reports in a database that’s open to the public." I'll post a link if and when I find one, but an excerpt is included in the story. He gave a brief history how those reports became public.

For those interested, here's SAPD's use of force policy. And while we're on the topic, here are a few other recent police accountability stories which merit Grits readers' attention:

From 2010 to 2015, police arrested more than 58,150 Anglo suspects and used force against them 1,175 times. That’s a rate of 20.2 incidents per 1,000 arrests.Overall, use of force increased dramatically at SAPD since 2010. "In raw numbers, incidents of force have increased by nearly 75 percent since 2010, from 735 cases that year to 1,281 in 2015." As demonstrated above, most of that increase involved black or Hispanic suspects. However, according to the department, "the primary reason for that increase ... is that the SAPD broadened the definition of force to include takedown maneuvers, which drastically increased the number of reports." Regrettably, the data was not broken out so that one could judge how much of the increase resulted from the data-definition change. ("Trust us, we're the government.)

For minorities, the rates of force nearly doubled over the same five years.

Police arrested 89,700 Hispanic suspects and used force against them 3,217 times — a rate of 35.9 incidents per 1,000 arrests.

Police arrested 23,045 African-American suspects and used force against them 822 times — a rate of 35.7 incidents per 1,000 arrests.

Tedesco does inform us that, "The San Antonio Police Department has compiled thousands of “use of force” reports in a database that’s open to the public." I'll post a link if and when I find one, but an excerpt is included in the story. He gave a brief history how those reports became public.

SAPD began requiring officers to fill out “use-of-force” reports in 1998 under the leadership of then-Chief Al Philippus, but the city refused to release the information to the public.Chief William Mcmanus defended his officers against allegations of racial bias, but seemed IMO to protest a bit too much.

The Express-News sued the city to obtain the records, arguing they fell under the Texas Public Information Act. During a legal battle that lasted years, the city lost at the trial and appellate court levels, and finally released the records in 2002 after the Texas Supreme Court declined to consider the case.

It was the first time the public had access to a repository of every force incident documented at the SAPD. But the reports only offer one side of the story — the Police Department’s.

“When you're using official records to do this, you're kind of at the mercy of how the Police Department codes it,” Terrill said. “They're coding it from an interested-party perspective, right?”

After receiving an updated copy of the database, the Express-News found many of the reports offer only scant or contradictory details about what exactly happened, making it difficult to compare the level of resistance of the suspect to the level of force used by the officer.

“The race or ethnicity of a suspect is not, nor has it ever been, a factor in determining whether to use force or the level of force used,” McManus said in a statement released Friday. “Any suggestion that our highly trained officers are choosing to use force based on any reason other than to protect themselves or others is false and disrespectful to our men and women in uniform.”Since we know for a fact that some of his "highly trained officers" have chosen to use force for reasons "other than to protect themselves or others," I call BS on that one. It's one thing to push back on the racial angle, but quite another to basically pre-clear every officer in every use of force incident without respect to the details. That's statement is "false" and "disrespectful" to the public whom he's treating in this story like gullible chumps.

For those interested, here's SAPD's use of force policy. And while we're on the topic, here are a few other recent police accountability stories which merit Grits readers' attention:

- AP: Police departments begin to reward restraint tactics

- Civil Beat: Why is it so hard to pass police reform in Hawaii?

- Black Lives Matter: Police Use of Force Database (100 departments)

Labels:

Bexar County,

Police,

use of force

Tuesday, April 05, 2016

Carlos Flores and the folly of secret police disciplinary files

At the SA Express-News, Rick Casey has a column following up on an episode discussed here on Grits involving the case of Carlos Flores. Despite having no criminal record, and contrary to his original claims that the officer had assaulted him, Mr. Flores pled no contest to assault on a public servant and later went to prison over probation violations. ("He missed several meetings with his supervision officer, hadn’t paid restitution or completed community service.") However:

Casey pointed out a disconnect in open-records and criminal discovery law that Grits has highlighted previously, including in relation to the Flores case. Hundreds of Texas law enforcement agencies operate with their disciplinary files subject to the Public Information Act, including all sheriffs departments except Harris County. But in police departments for 73 or so Texas municipalities, big and small, which have adopted the state civil service code, those files are secret except for brief summaries of episodes for which officers receive the most serious punishments. As with police use of Stingray surveillance equipment, even prosecutors can't see the records.

Clearly there's a structural problem. Information in police disciplinary files often qualifies as impeachment evidence which, under Brady v. Maryland and the Michael Morton Act, Texas prosecutors are obligated to produce. But that's a problem with a (legislative) solution. Since we know that hundreds of cities already operate with police disciplinary files subject to the Public Information Act - Dallas and El Paso are the two largest that never adopted the state civil service code - there's no reason to believe removing that open-records exemption would be harmful or unworkable.

Grits has previously suggested a simple legislative fix to this: "Just eliminate (f) and (g) in Local Government Code 143.089 to open those records to the same extent as at county sheriffs and hundreds of other Texas law enforcement agencies. Or perhaps they should just strike 143.089 altogether. Maybe the state doesn't need to regulate what's in a local department's disciplinary files so long as they're open." Easy peasy.

One also notices, though, that in this case, the officer who attacked Flores was given a 30-day suspension, which should have been long enough, even under the civil-service code, for the police department to be required to release summary information regarding a sustained complaint. So, while it's surely true the police department didn't forward the exculpatory information, it's also clear the DA's office wasn't tracking police-officer misconduct because that decision would have been a public record. Under the new DA, Nico Lahood, Casey reported, the office "has developed a list of officers in the county’s numerous police agencies whose disciplinary records should be disclosed to defense attorneys." So maybe that sort of proactive information gathering is happening now in Bexar County.

Prosecutors definitely should disclose police misconduct to the defense when they know of it, and the Michael Morton Act relieved them of any obligation to determine if the misconduct is material to the case, they simply have to disclose it. But if disciplinary files in civil-service cities were made a public record, as is the case in most law-enforcement agencies across the state, chances would improve greatly in any given instance that defense counsel will get hold of the information even if prosecutors conceal it. Plus, there are numerous other public-interest reasons for disclosing police misconduct beyond compliance with the Michael Morton Act. FWIW, Texas isn't the only state struggling with exactly this issue.

What Flores wasn’t told, nor was the DA’s office, was that the Police Department determined that the officer had filed a false report on the Flores case and had violated department policy by not taking the seriously injured man to the hospital before booking him. The officer was suspended for 30 days without pay.According to the FBI, who interviewed Flores a month before his conviction, this wasn't the only episode in which Officer Belver was alleged to have beaten up suspects.

Photographs reportedly showed Flores with a severely beaten face and the officer with only a small mark on his.

Based on this and other evidence, the district attorney’s Conviction Integrity Unit filed a motion to dismiss the charges.

Casey pointed out a disconnect in open-records and criminal discovery law that Grits has highlighted previously, including in relation to the Flores case. Hundreds of Texas law enforcement agencies operate with their disciplinary files subject to the Public Information Act, including all sheriffs departments except Harris County. But in police departments for 73 or so Texas municipalities, big and small, which have adopted the state civil service code, those files are secret except for brief summaries of episodes for which officers receive the most serious punishments. As with police use of Stingray surveillance equipment, even prosecutors can't see the records.

Clearly there's a structural problem. Information in police disciplinary files often qualifies as impeachment evidence which, under Brady v. Maryland and the Michael Morton Act, Texas prosecutors are obligated to produce. But that's a problem with a (legislative) solution. Since we know that hundreds of cities already operate with police disciplinary files subject to the Public Information Act - Dallas and El Paso are the two largest that never adopted the state civil service code - there's no reason to believe removing that open-records exemption would be harmful or unworkable.

Grits has previously suggested a simple legislative fix to this: "Just eliminate (f) and (g) in Local Government Code 143.089 to open those records to the same extent as at county sheriffs and hundreds of other Texas law enforcement agencies. Or perhaps they should just strike 143.089 altogether. Maybe the state doesn't need to regulate what's in a local department's disciplinary files so long as they're open." Easy peasy.

One also notices, though, that in this case, the officer who attacked Flores was given a 30-day suspension, which should have been long enough, even under the civil-service code, for the police department to be required to release summary information regarding a sustained complaint. So, while it's surely true the police department didn't forward the exculpatory information, it's also clear the DA's office wasn't tracking police-officer misconduct because that decision would have been a public record. Under the new DA, Nico Lahood, Casey reported, the office "has developed a list of officers in the county’s numerous police agencies whose disciplinary records should be disclosed to defense attorneys." So maybe that sort of proactive information gathering is happening now in Bexar County.

Prosecutors definitely should disclose police misconduct to the defense when they know of it, and the Michael Morton Act relieved them of any obligation to determine if the misconduct is material to the case, they simply have to disclose it. But if disciplinary files in civil-service cities were made a public record, as is the case in most law-enforcement agencies across the state, chances would improve greatly in any given instance that defense counsel will get hold of the information even if prosecutors conceal it. Plus, there are numerous other public-interest reasons for disclosing police misconduct beyond compliance with the Michael Morton Act. FWIW, Texas isn't the only state struggling with exactly this issue.

Thursday, January 28, 2016

Jailing the mentally ill

From the Hogg Foundation, see a Houston Chronicle column (Jan. 18) titled, "Texas, stop treating mental illness like it's a crime."

Without question, some people with mental illness need to be incarcerated. But for low-level nonviolent offenders, we should look to measures that can divert people from jails and into community-based mental health treatment programs.Meanwhile, the SA Express News published a column (Jan. 22) by Sheriff Susan Parmerleau touting Bexar County's much-admired mental health diversion program, which has garnered national praise and generated impressive results:

The sequential-intercept model is a good example and highlights how this process of diversion can happen at every point along the criminal justice continuum - from the moment the 911 call is placed all the way to re-entry into the community after incarceration.

What's required are common-sense reforms such as targeted training for police and 911 dispatchers, screening for behavioral health conditions at the early stages of the process, and improved coordination between the justice system and social service agencies. For example, re-entry peer support, in which a recently released person is paired with a trained mentor who's been through the same experience, has been tested in Pennsylvania with promising results. The Texas Legislature approved up to $1 million in funding last session for two pilot sites. Scaling of such a program, if the pilots prove successful, could make an enormous difference.

Another good example is the improved protocol for 911 dispatchers in Houston, which requires that all callers be asked if their call involves a mental-health issue. Callers who say yes are routed to special crisis counselors who work out of the police department and can often deal appropriately with a situation without even bringing law enforcement into it.

We should take these kinds of steps because it's not only the right thing to do, the time is right. The evidence base for diversion programs has matured to the point where we can have confidence that the money will be well-spent. Law enforcement officials across the country support such measures. And advocates, experts and policymakers are recognizing that systemic change is needed to address systemic problems. It's time for more Texas lawmakers to get on board.

The results have been remarkable. In 2009, the 15 deputies assigned to our mental health unit received crisis intervention training, which teaches them how to recognize someone in a mental health crisis and how to de-escalate the situation. Prior to 2009, our mental health deputies had to use physical force, on average, 50 times a year taking those with mental health issues into custody. Since that time, in more than six years, force has only had to be used three times. The difference between 300 times and three times is dramatic.

Since this program was started, more than 20,000 people with serious mental illness have been identified and diverted from jail into treatment. And the program has contributed significantly to resolving the problem of overcrowding in the jail.

Bexar County’s improvements in responding to people in crisis have also led to significant savings by reducing incarceration and emergency room use. In the past five years, the jail diversion program has saved Bexar County more than $50 million. This has been achieved through wise investments in community mental health services, and hiring more professionals to provide treatment. It has also succeeded by focusing resources on rehabilitation, housing and employment assistance. ...

Jails have become de facto mental institutions, and that has to change. As we work together as a community, we can provide those with mental illness the help they need. Those suffering with mental illness need treatment programs, not jail cells.Finally, UT-Austin academic William Kelly offered up an interesting critique of the mens rea debate going on at the federal level, arguing that the real mens rea issues in the criminal justice system relate to mental illness:

Today, 40 percent of individuals in the U.S. criminal justice system (federal and state) have a diagnosable mental illness. Sixty percent of inmates in the nation’s prisons have experienced at least one traumatic brain injury. Nearly 80 percent of justice-involved individuals have a substance abuse problem. The prevalence in the justice system of individuals with intellectual disabilities is three to five times what it is in the general population. There are substantial numbers of individuals in the justice system with neurodevelopmental and neurocognitive deficits and impairments.

Moreover, there’s overwhelming evidence that many individuals with mental illness, addiction, neurodevelopmental deficiencies, and intellectual deficits lack the ability to form intent as it is defined in the law. How many lack this ability we don’t really know, because we rarely inquire about intent. But the statistics cited above should raise serious questions about how we go about the business of criminal justice in the U.S.

In the vast majority of state and federal criminal convictions, the government rarely is required to prove intent. That’s because the vast majority of criminal indictments (roughly 95 percent) are resolved through a plea agreement. If the offender agrees to the terms of the agreement, it’s essentially a done deal. That puts prosecutors in charge of sorting out who is criminally responsible and who is not. At the end of the day, the vast majority are held responsible.

Mens rea is supposed to serve as a gatekeeper at the front door of the justice system, separating innocent from criminal behavior. The reality is that criminal intent is just not much of an issue under current criminal procedure. That in turn has significantly contributed to our incarceration problem by facilitating the punishment of more and more individuals.

It has also contributed to our recidivism problem.

When we punish mentally ill, addicted, intellectually disadvantaged and/or neurocognitively impaired individuals, we tend to return them to the free world in worse shape than when they came in. This is simply more grease for the revolving door.

Labels:

Bexar County,

County jails,

Mental health

Thursday, December 10, 2015

They said you want kill people and not go to jail?? I said 'F--- ya'

Grits can't believe San Antonio PD let this officer back on the force. What do they think their constituents will say the day he shoots somebody? From the SA Express-News (Dec. 9):

A San Antonio Police Department officer was suspended for 30 days without pay for a social media post, according to records obtained by mySA.com

Officer Daryl A. Carle received the punishment after SAPD found a Facebook post on Carle's profile in August, suspension documents show.San Antonio already faces enough problems on the police shootings front, keeping this guy on the force seems like they're just asking for karma to come smack them later. The entitlement to free speech is not an entitlement to a job.

“I love my job!!! They said you want kill people and not go to jail?? I said “F--- ya, Who don’t?... They said you afraid of the jungle?? I said “I ain’t scared of sh--... I’ve been wanting go jungle since watched that Predator movie…I love my job!!!!!! Lol," the post said, records show.

SAPD Chief William McManus said in a sit-down interview Wednesday that Carle told him the origin of the post was a quote from a YouTube video series.

The series, “Action Figure Therapy,” which posts funny and sometimes vulgar videos of action figures ranting about military and tactical topics. (The linked video contains NSFW language.)

Labels:

Bexar County,

disciplinary process,

Police

Saturday, December 05, 2015

Raft of misconduct in San Antonio points to bigger problems in police contract

Police accountability politics in San Antonio are becoming increasingly layered, complex, and interesting. The local police union went all in for Leticia Van de Putte's mayoral campaign, only to see her swatted by GOP voters in northern San Antonio who backed Ivy Taylor, standing up to Alinskyite bullies.

Since then, the union walked away from collective bargaining negotiations because Mayor Taylor insisted on suing to get rid of an "evergreen" clause in the last contract which extends its terms for ten years if the parties can't agree on new ones.

Meanwhile, as street protests continued in October over the 2014 death of Marquise Jones, news arose last month that another man, who was severely beaten by police in 2014 when he was mistaken for a suspect while standing in front of his wife's business, was paralyzed from his injuries:

Less well publicized, but no less significant, in October, courts exonerated Carlos Flores after it was revealed that a SAPD officer in 2009 beat him while handcuffed. Flores was then charged with, and ultimately pled no contest to, assault on a public servant. The police department concealed from prosecutors evidence that the officer beat the handcuffed man and his supervisors all knew about it. (BTW, the lack of coverage on this case to me is inexplicable. This story wouldn't be overlooked if Eva Ruth Moravec or Michelle Mondo were still writing for the Express-News.)

On the county side, after video was released this summer of Bexar County Sheriff's deputies apparently shooting a man with his hands up, a deputy was arrested last month for aggravated sexual assault of a child, and the accompanying story mentioned that, "The sheriff's office also said of the now 14 deputies arrested this year, only three remain employed by BCSO." I don't know what's typical, but that sounds to this writer like an awful lot of deputies arrested for one 12-month span.

Debates surrounding San Antonio's police union contract have been strangely disconnected from police accountability issues, even as these stories of questionable shootings and serious misconduct swirl in the press at both the city and county level. The city has focused on seeking economic concessions from the union, and that alone has driven them away from the bargaining table. When the parties finally go back to the bargaining table, the city should get serious about strengthening the disciplinary process laid out in the contract.

A 2011 report from the Texas Civil Rights Project detailed 41 recommendations for addressing misconduct by SAPD officers, many of which probably couldn't be implemented under the terms of the meet-and-confer agreement.

There are two possible scenarios. If city officials win their lawsuit disputing the antidemocratic "evergreen clause," they go back to the bargaining table with the leverage needed to open up that broader discussion. If they lose, they go back with almost no leverage. (No matter who wins now, the other party is almost certain to appeal.)

The union has made it clear they will just sit tight indefinitely since their evergreen clause locks in current disciplinary rules and benefits until September 30, 2024 unless overturned by the court.

And once a new contract is signed, there's no second bite at that apple for years, no matter how many terrible incidents surface or how much money the city has to dole out in lawsuit settlements.

Notably, the national Black Lives Matter campaign has created the Campaign Zero project designed to help people demand accountability in cities which have negotiated union contracts. Here in Texas, that fight will inevitably migrate to the Texas capitol in 2017 where most of the provisions originated that protect problem officers in civil-service cities like San Antonio.

RELATED: From The Atlantic (Dec. 7), "Black Lives Matter Takes Aim at Police Union Contracts."

Since then, the union walked away from collective bargaining negotiations because Mayor Taylor insisted on suing to get rid of an "evergreen" clause in the last contract which extends its terms for ten years if the parties can't agree on new ones.

Meanwhile, as street protests continued in October over the 2014 death of Marquise Jones, news arose last month that another man, who was severely beaten by police in 2014 when he was mistaken for a suspect while standing in front of his wife's business, was paralyzed from his injuries:

A man beaten by three San Antonio Police officers last year is paralyzed from the chest down after complications during surgery to repair his injured spine, his family confirmed to the KENS 5 I-Team.

Roger Carlos, 43, was paralyzed during surgery November 3 at a San Antonio area hospital.

Doctors have performed multiple surgeries on Carlos's neck and upper spine to relieve pain and pressure from herniated discs, following his May 2014 beating at the hands of two SAPD SWAT officers and a drug task force officer.Notably, in that case, "A police discipline board recommended 15-day suspensions for all three officers. Chief William McManus, who did not respond to a request for interview ... later shortened each of the suspensions to five days." Moreover, "All three officers used accrued leave time instead of serving their suspensions." So, hardly any disciplinary action at all.

Less well publicized, but no less significant, in October, courts exonerated Carlos Flores after it was revealed that a SAPD officer in 2009 beat him while handcuffed. Flores was then charged with, and ultimately pled no contest to, assault on a public servant. The police department concealed from prosecutors evidence that the officer beat the handcuffed man and his supervisors all knew about it. (BTW, the lack of coverage on this case to me is inexplicable. This story wouldn't be overlooked if Eva Ruth Moravec or Michelle Mondo were still writing for the Express-News.)

On the county side, after video was released this summer of Bexar County Sheriff's deputies apparently shooting a man with his hands up, a deputy was arrested last month for aggravated sexual assault of a child, and the accompanying story mentioned that, "The sheriff's office also said of the now 14 deputies arrested this year, only three remain employed by BCSO." I don't know what's typical, but that sounds to this writer like an awful lot of deputies arrested for one 12-month span.

Debates surrounding San Antonio's police union contract have been strangely disconnected from police accountability issues, even as these stories of questionable shootings and serious misconduct swirl in the press at both the city and county level. The city has focused on seeking economic concessions from the union, and that alone has driven them away from the bargaining table. When the parties finally go back to the bargaining table, the city should get serious about strengthening the disciplinary process laid out in the contract.

A 2011 report from the Texas Civil Rights Project detailed 41 recommendations for addressing misconduct by SAPD officers, many of which probably couldn't be implemented under the terms of the meet-and-confer agreement.

There are two possible scenarios. If city officials win their lawsuit disputing the antidemocratic "evergreen clause," they go back to the bargaining table with the leverage needed to open up that broader discussion. If they lose, they go back with almost no leverage. (No matter who wins now, the other party is almost certain to appeal.)

The union has made it clear they will just sit tight indefinitely since their evergreen clause locks in current disciplinary rules and benefits until September 30, 2024 unless overturned by the court.

And once a new contract is signed, there's no second bite at that apple for years, no matter how many terrible incidents surface or how much money the city has to dole out in lawsuit settlements.

Notably, the national Black Lives Matter campaign has created the Campaign Zero project designed to help people demand accountability in cities which have negotiated union contracts. Here in Texas, that fight will inevitably migrate to the Texas capitol in 2017 where most of the provisions originated that protect problem officers in civil-service cities like San Antonio.

RELATED: From The Atlantic (Dec. 7), "Black Lives Matter Takes Aim at Police Union Contracts."

Labels:

Bexar County,

civil service code,

disciplinary process,

Innocence,

Police,

unions

Monday, November 16, 2015

Open up police disciplinary files to honor Michael Morton Act obligations

In the comments to this Grits post on the exoneration of Carlos Flores, Jay Brandon, chief of the Bexar County DA's Conviction Integrity Unit rightly deflected blame from prosecutors in the case. Wrote Brandon:

It makes no sense that these records would be secret at San Antonio PD and public if the same thing has happened to a Bexar County Sheriff's deputy, but that's how state law presently treats law enforcement disciplinary records. Most cities which operate under the civil service code voted to opt in in the '40s and '50s, decades before the Legislature changed the law in 1989 to close civil-service disciplinary files.

Understandably, prosecutors like Mr. Brandon don't want the DA to be blamed because police kept something secret. And police in Texas' 73 or so civil-service cities can claim state law mandates they can't share disciplinary files ... which is true, or at least has been since 1989, when the unions got the law changed. So everybody gets to pass blame to the next guy until we get to the Texas Legislature, which both created the problem and is the branch of government most readily in a position to fix it. (The courts could do it, but that would get messy.)

So yes, even though Grits stands by the headline that the "State hid evidence," in this case that doesn't imply prosecutorial misconduct. But the episode demonstrates that the "state's" responsibility is a shared one. It can't just be on prosecutors or they can't fulfill their duties. Police and ultimately, the Legislature, must do their part or the portion of the law requiring impeachment evidence about officers to be handed over to the defense becomes a dead letter: Prosecutors can't turn over materials they themselves never see.

The Lege should remove this excuse for civil-service departments - which are only a few dozen agencies out of 2,600+ statewide, though they include some of the largest - to thumb their noses at prosecutors and their Michael Morton Act and Brady v. Maryland obligations. Just eliminate (f) and (g) in Local Government Code 143.089 to open those records to the same extent as at county sheriffs and hundreds of other Texas law enforcement agencies. Or perhaps they should just strike 143.089 altogether. Maybe the state doesn't need to regulate what's in a local department's disciplinary files so long as they're open.

I am the chief of the conviction integrity unit in the Bexar County DA's office, and I handled this case post-conviction. Police never forwarded this information to the District Attorney's Office until a couple of years after the conviction, when a writ was filed. It was at my suggestion and with my cooperation that the defense subpoenaed the records that showed the disciplinary action. This wasn't a case of prosecutors hiding evidence, it was a case of a properly conducted post-conviction review by the District Attorney's Office.Closed police disciplinary files in civil service cities have long been a hobby horse for this blog. But only after passage of the Michael Morton Act, which explicitly demands that impeachment material be handed over, has the issue come clearly into focus among the various stakeholders. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals' Criminal Justice Integrity Unit identified this issue in the early months after the law took effect.

It makes no sense that these records would be secret at San Antonio PD and public if the same thing has happened to a Bexar County Sheriff's deputy, but that's how state law presently treats law enforcement disciplinary records. Most cities which operate under the civil service code voted to opt in in the '40s and '50s, decades before the Legislature changed the law in 1989 to close civil-service disciplinary files.

Understandably, prosecutors like Mr. Brandon don't want the DA to be blamed because police kept something secret. And police in Texas' 73 or so civil-service cities can claim state law mandates they can't share disciplinary files ... which is true, or at least has been since 1989, when the unions got the law changed. So everybody gets to pass blame to the next guy until we get to the Texas Legislature, which both created the problem and is the branch of government most readily in a position to fix it. (The courts could do it, but that would get messy.)

So yes, even though Grits stands by the headline that the "State hid evidence," in this case that doesn't imply prosecutorial misconduct. But the episode demonstrates that the "state's" responsibility is a shared one. It can't just be on prosecutors or they can't fulfill their duties. Police and ultimately, the Legislature, must do their part or the portion of the law requiring impeachment evidence about officers to be handed over to the defense becomes a dead letter: Prosecutors can't turn over materials they themselves never see.

The Lege should remove this excuse for civil-service departments - which are only a few dozen agencies out of 2,600+ statewide, though they include some of the largest - to thumb their noses at prosecutors and their Michael Morton Act and Brady v. Maryland obligations. Just eliminate (f) and (g) in Local Government Code 143.089 to open those records to the same extent as at county sheriffs and hundreds of other Texas law enforcement agencies. Or perhaps they should just strike 143.089 altogether. Maybe the state doesn't need to regulate what's in a local department's disciplinary files so long as they're open.

Labels:

Bexar County,

civil service code,

District Attorneys,

Police

Wednesday, November 11, 2015

Latest Texas exoneration: State hid evidence cop beat suspect while handcuffed, prosecuted victim; FBI says not a one-off

Check out the most recent Texas exoneration from the National Exoneration Registry: Carlos Flores, who allegedly was beaten by San Antonio Police Officer Matthew Belver while handcuffed, then charged with assaulting an officer.

But that's quite a fact-pattern for an innocence case! One wonders what information SAPD Internal Affairs and the feds had that made them believe the word of the suspect over Officer Belver?

Flores, a legal permanent resident from Mexico with no criminal record, was charged with assault on a public servant. Flores filed a complaint with the San Antonio Police Department accusing Belver of attacking him while he was handcuffed and asserting that he kicked at Belver in self-defense.The Court of Criminal Appeals ruled in Flores' favor based on a Brady claim, not actual innocence, even though the evidence prosecutors concealed "is consistent with Applicant's contention that he did not intentionally or knowingly assault the officer."

Flores said in his complaint that after Belver handcuffed him and placed him in the back of the police car, he told Belver, “I want to kick your ass.” Flores said Belver opened the back door of the police car, yanked him out onto the ground and began beating him while he was still handcuffed. During the tussle, Flores said he kicked Belver in the face.

Belver radioed for assistance, but had managed to put Flores back into the police car by the time other officers arrived.

In May 2011, Flores received a letter from the San Antonio Police Department informing him that after an Internal Affairs Unit investigation, “corrective action” was taken against Belver, but did not specify the nature of the action except to say it would be “noted in his personnel file” and would serve “as a reference in the event there a reoccurrence of this type of action by the officer.

On December 6, 2011, Flores pled no contest to assault on a public servant in Bexar County Criminal District Court and the judge deferred an adjudication of guilt for four years. He was ordered to complete 350 hours of community service and pay $2,300 in restitution to the police department.

In April 2013, the FBI reached out to Flores to interview him because Belver was the subject of a federal investigation into allegations that [he] was beating people while making arrests and conducting improper searches without warrants.

One month later, in May 2013, Flores’s deferred adjudication was revoked because he missed three meetings with his court supervision officer, had only paid $600 in restitution and had not completed his community service. He was sentenced to prison for three years.

In May 2014, Flores was scheduled to be released from prison on parole and discovered that because of his conviction, he was subject to deportation.

In October 2014, Flores filed a state-court petition for a writ of habeas corpus seeking to vacate his conviction on the basis of actual innocence. The petition said that although the FBI investigation had not resulted in any charges against Belver, he had been suspended for 30 days without pay for filing a false report of his arrest of Flores and for failing to take Flores for medical treatment on the day of the arrest.

A hearing was held on the petition and the Bexar County District Attorney’s Office agreed that the information should have been disclosed to Flores prior to his guilty plea. A judge recommended that the writ be granted.

In September 2015, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals granted the writ and vacated the conviction. “This information was not disclosed to the defense before (Flores) entered his plea, and is consistent with (his) contention that he did not intentionally or knowingly assault the officer,” the appeals court said. “The trial court conducted a habeas hearing, and the parties agree that the information regarding the disciplinary action against the arresting officer should have been, but was not disclosed to the defense in this case.”

In October 2015, the Bexar County District Attorney’s Conviction Integrity Unit filed a motion to dismiss the charge. On October 21, 2015, the motion was granted and Flores was released.

But that's quite a fact-pattern for an innocence case! One wonders what information SAPD Internal Affairs and the feds had that made them believe the word of the suspect over Officer Belver?

Labels:

Bexar County,

Brady violations,

Innocence,

Police,

use of force

Tuesday, September 01, 2015

Reviewing 2015 criminal justice reforms, and other stories

Here are several recent stories which merit Grits readers' attention:

Reviewing criminal justice bills from 84th Texas Legislature

See the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition's 84th session wrap-up document.

Debating legacy of Texas 2007 de-incarceration reforms

The Texas Criminal Justice Coalition's Ana Correa and Marc Levin from the Texas Public Policy Foundation co-authored a column which implicitly replied to an earlier guest column minimizing the importance of reform measures passed eight years ago. Grits earlier offered my own rebuttal to the piece.

Too many jails get loophole in bill requiring in-person visitation

The bill to preserve in-person visitation at county jails was a bit of a mess, reported the Dallas News, leaving room for counties to game the system and pretend they're already invested in new systems to get in under an arbitrary deadline. There should be some means to go back and force these agencies to enable in-person visits, especially for those who announced their interest in changing over only after the bill was filed.

Sheriff blames deputy's murder on Black Lives Matter

A mentally ill man shot a Harris County Sheriff's Deputy and the Sheriff blamed the Black Lives Matter movement based on exactly zero evidence. The Harris County Sheriff runs the largest mental hospital in Texas, but he ignores the mental illness angle and blames his political enemies. Pathetic.

Hands up!

Two Bexar County Sheriff's deputies shot a man who supposedly had his hands up at the time. KSAT-TV paid $100 for cell phone video of the killing, which seems to have the Sheriff's Office more hot and bothered than what their employees did.

Kids or Criminals?

That was the title of a Dallas Morning News feature on youth who grow up incarcerated.

Be sad - but not scared

Here's a good editorial from the Fort Worth Star-Telegram putting coverage of violent crime into perspective.

Oliver Sacks on the reliability of eyewitnesses

Neuroscientist Oliver Sacks passed away recently and his death reminded me of an excellent short essay he wrote a couple of years back on the reliability of eyewitness identification. I've read several of his books; his passing was a loss.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this post misread data from a DPS gang assessment report and that sub-item has been removed as has the reference to it in the headline. Grits regrets the error.

Reviewing criminal justice bills from 84th Texas Legislature

See the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition's 84th session wrap-up document.

Debating legacy of Texas 2007 de-incarceration reforms

The Texas Criminal Justice Coalition's Ana Correa and Marc Levin from the Texas Public Policy Foundation co-authored a column which implicitly replied to an earlier guest column minimizing the importance of reform measures passed eight years ago. Grits earlier offered my own rebuttal to the piece.

Too many jails get loophole in bill requiring in-person visitation

The bill to preserve in-person visitation at county jails was a bit of a mess, reported the Dallas News, leaving room for counties to game the system and pretend they're already invested in new systems to get in under an arbitrary deadline. There should be some means to go back and force these agencies to enable in-person visits, especially for those who announced their interest in changing over only after the bill was filed.

Sheriff blames deputy's murder on Black Lives Matter

A mentally ill man shot a Harris County Sheriff's Deputy and the Sheriff blamed the Black Lives Matter movement based on exactly zero evidence. The Harris County Sheriff runs the largest mental hospital in Texas, but he ignores the mental illness angle and blames his political enemies. Pathetic.

Hands up!

Two Bexar County Sheriff's deputies shot a man who supposedly had his hands up at the time. KSAT-TV paid $100 for cell phone video of the killing, which seems to have the Sheriff's Office more hot and bothered than what their employees did.

Kids or Criminals?

That was the title of a Dallas Morning News feature on youth who grow up incarcerated.

Be sad - but not scared

Here's a good editorial from the Fort Worth Star-Telegram putting coverage of violent crime into perspective.