Showing posts with label Nueces County. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Nueces County. Show all posts

Friday, October 25, 2019

The state of 'progressive prosecutors' in Texas

The article in The Atlantic titled "Texas prosecutor fights for reform" has a certain "Man Bites Dog" quality, which I suppose makes local news from Texas interesting enough for East and West coast media and muckety mucks to take notice. Not that John Creuzot's work in Dallas doesn't deserve attention. In Grits' view, he is the most confident, competent, and sure-footed of Texas' new crop of Democratic DAs. But at this point, the term "progressive district attorney" requires so many caveats that it should probably be discarded, at least in red states, until a few key benchmarks have been established and met.

When Kim Ogg of Houston, Mark Gonzalez in Corpus Christi, and Margaret Moore in Austin were elected DAs of their respective counties in 2016, there was a clutch of mostly national advocates and journalists, coupled with a few local electoral partisans, who pronounced them part of a new wave of "progressive prosecutors." Grits argued at the time that there was no such thing (and still largely thinks that's true).

Larry Krasner's election in Philadelphia changed things. His office produced a memo detailing new policies aimed at reducing incarceration rates that was much more daring and aggressively decarceral than any previous US prosecutor had ever suggested. (For a contemporary podcast discussion of Krasner's memo in context of Texas candidates, see here.) Soon, prosecutors in other states began running mimicking parts of Krasner's approach as well as expanding or exploring other decarceral programs.

In Texas, though, the decarceral efforts of our Democratic DAs have been much more modest.

Harris and Travis Counties have created special courts for state-jail felonies that have helped chip away at state-jail incarceration rates. Joe Gonzalez in San Antonio took a won't-prosecute stance on low-level pot possession (Ogg created a pretrial diversion program for pot.) And both Mark Gonzalez and Margaret Moore found themselves in the happy position to replace such embarrassingly bad prosecutors, they could look like an improvement just by avoiding overt misconduct and not drooling on themselves in public.

On bail reform, in particular, for the most part these prosecutors' positions are far from "progressive." And even if they are, as with Creuzot, judges, local criminal-defense attorneys, and other special interests have proven effective at throwing a monkey wrench into potential solutions.

Ogg in particular has chosen to pick fights with county commissioners, newly elected Democratic judges, reformers, journalists, and academics over every perceived slight, leaving herself ever-more frustrated and isolated. Most prominently, she attacked the pending bail-reform settlement and demanded the county radically increase her staff size without acknowledging how that would a) create disadvantages for underfunded indigent defense or b) run counter to decarceration goals. (Recently a group of scholars came out to criticize the methodology of a study her office promoted to justify the request for more staff.)

Creuzot was the first Texas DA to more comprehensively articulate his own decarceral agenda, sort of a Larry-Krasner-Lite, but whose pronouncements are peppered with "y'alls." His policies were more modest than, say, newly elected prosecutors in Philly, St. Louis, or Boston. Even so, there's no doubt Creuzot's positions were more concrete and his thinking about decarceration is the most-well-developed of any Lone-Star prosecutor. Indeed, his general election vs. a Republican incumbent essentially centered around which one of them would be more reform-minded.

By contrast, in Houston, some of the same reform voices who prematurely hailed Kim Ogg as a progressive in 2016 are calling for her replacement by Audia Jones. Margaret Moore last year asked local reformers to endorse her push to merge the District and County Attorney offices under her control, but refused to enact any of the reforms local advocates wanted in return. As a result, the merger didn't happen and she now faces a serious reform challenger in Jose Garza.

Going forward, if any of these insurgents win in the coming Democratic primaries, then the terrain will have shifted and "progressive" will no longer effectively serve as a synonym for "Democrat" in Texas when it comes to prosecutor elections, as seems to have been the case so far.

When Kim Ogg of Houston, Mark Gonzalez in Corpus Christi, and Margaret Moore in Austin were elected DAs of their respective counties in 2016, there was a clutch of mostly national advocates and journalists, coupled with a few local electoral partisans, who pronounced them part of a new wave of "progressive prosecutors." Grits argued at the time that there was no such thing (and still largely thinks that's true).

Larry Krasner's election in Philadelphia changed things. His office produced a memo detailing new policies aimed at reducing incarceration rates that was much more daring and aggressively decarceral than any previous US prosecutor had ever suggested. (For a contemporary podcast discussion of Krasner's memo in context of Texas candidates, see here.) Soon, prosecutors in other states began running mimicking parts of Krasner's approach as well as expanding or exploring other decarceral programs.

In Texas, though, the decarceral efforts of our Democratic DAs have been much more modest.

Harris and Travis Counties have created special courts for state-jail felonies that have helped chip away at state-jail incarceration rates. Joe Gonzalez in San Antonio took a won't-prosecute stance on low-level pot possession (Ogg created a pretrial diversion program for pot.) And both Mark Gonzalez and Margaret Moore found themselves in the happy position to replace such embarrassingly bad prosecutors, they could look like an improvement just by avoiding overt misconduct and not drooling on themselves in public.

On bail reform, in particular, for the most part these prosecutors' positions are far from "progressive." And even if they are, as with Creuzot, judges, local criminal-defense attorneys, and other special interests have proven effective at throwing a monkey wrench into potential solutions.

Ogg in particular has chosen to pick fights with county commissioners, newly elected Democratic judges, reformers, journalists, and academics over every perceived slight, leaving herself ever-more frustrated and isolated. Most prominently, she attacked the pending bail-reform settlement and demanded the county radically increase her staff size without acknowledging how that would a) create disadvantages for underfunded indigent defense or b) run counter to decarceration goals. (Recently a group of scholars came out to criticize the methodology of a study her office promoted to justify the request for more staff.)

Creuzot was the first Texas DA to more comprehensively articulate his own decarceral agenda, sort of a Larry-Krasner-Lite, but whose pronouncements are peppered with "y'alls." His policies were more modest than, say, newly elected prosecutors in Philly, St. Louis, or Boston. Even so, there's no doubt Creuzot's positions were more concrete and his thinking about decarceration is the most-well-developed of any Lone-Star prosecutor. Indeed, his general election vs. a Republican incumbent essentially centered around which one of them would be more reform-minded.

By contrast, in Houston, some of the same reform voices who prematurely hailed Kim Ogg as a progressive in 2016 are calling for her replacement by Audia Jones. Margaret Moore last year asked local reformers to endorse her push to merge the District and County Attorney offices under her control, but refused to enact any of the reforms local advocates wanted in return. As a result, the merger didn't happen and she now faces a serious reform challenger in Jose Garza.

Going forward, if any of these insurgents win in the coming Democratic primaries, then the terrain will have shifted and "progressive" will no longer effectively serve as a synonym for "Democrat" in Texas when it comes to prosecutor elections, as seems to have been the case so far.

Monday, September 30, 2019

'Progressive prosecutors' not all so progressive on bail reform

At the Texas Tribune festival this weekend, Josie Duffy-Rice, president of The Appeal, moderated a panel with three Democratic Texas District Attorneys - John Creuzot of Dallas, Margaret Moore of Travis County, and Mark Gonzalez of Nueces County.

An audience member asked the panelists whether they favored providing defense attorneys to defendants at "magistration," where judges set bail amounts defendants must pay to get out of jail pending trial.

Gonzalez failed to answer the question directly, conflating magistration with plea bargaining and insisting that his office was more fair than his predecessor.

Moore also talked around the issue, but in essence said she didn't think providing counsel at bail hearings was necessary. Prosecutors don't even attend those hearings in Travis County, she declared, an assertion which Grits found dubious. After all, the county indigent defense plan anticipates prosecutors may "fil[e] an application" with the court at magistration, while indigent defendants may apply for an attorney at that point, but don't get one until later. Moore suggested that a post hoc bail-review hearing was sufficient to protect defendants' liberty interests.

Creuzot was the only DA who said, definitively, "Yes," defense attorneys should be provided at magistration. He blamed Dallas judges who appealed the federal injunction for blocking the move, although at least one judge supports the idea. (The county commissioners court, which would have to come up with money to pay for additional defense counsel, surely also is a barrier to implementing that idea.)

Grits found this discussion dissatisfying, given recent developments in Texas bail-reform litigation.

In Galveston, in particular, a recent federal-court injunction explicitly required the county to provide attorneys at magistration. This was not mentioned.

Harris County eliminated magistration in 85 percent of misdemeanor cases to avoid having to make individualized determinations, and launched a pilot program to provide a public defender at bail hearings for the other 15 percent.

In Dallas, a federal judge said magistrates couldn't rely on a pre-set bail schedule without considering individual circumstances. Articulating those, of course, is a defense attorney's job. The injunction has been appealed, but the judge's order would require these hearings to occur within 48 hours of arrest.

So, if we're reading tea leaves here, in all three jurisdictions, federal judges have said that non-individualized bail hearings are unacceptable and that release decisions must be made promptly.

In that light, claims that it's sufficient to review non-individualized bail decisions later, as DA Moore declared, strike me as optimistic, at best. All the federal court rulings in Texas so far have required more.

Certainly it's insufficient to address the issue during plea bargaining, as Mark Gonzalez maintained! Part of the problem with excessive pretrial detention is that it makes defendants more likely to accept unfavorable plea bargains.

The US constitution forbids "excessive bail," not bail per se, so it's unlikely federal courts will ever "abolish money bail," as most #cjreform advocates would prefer. But it also seems clear to this observer that federal courts will eventually require individualized bail determinations, likely at magistration.

We've now seen three different options emerge from federal courts for how to do that: Provide counsel at magistration, as in Galveston; hold individualized hearings within 48 hours of arrest, as in Dallas; or simply eliminate bail determination hearings for most nonviolent cases, and provide lawyers at magistration for the remaining subset, as Harris County is doing.

No one can tell which of these options will be required writ large across Texas until the 5th Circuit rules in one of these cases. Now that the Harris County suit has settled, it seems likely that Dallas will be the first to reach that stage. Their preliminary injunction came out more than a year ago, while Galveston's only emerged last month.

Regardless, Creuzot was the only DA on the so-called "progressive prosecutor" panel who gave what Grits would consider a "progressive" answer on bail reform. Letting folks sit around in jail because they're too poor to pay just isn't good enough, anymore.

|

| (L-R) Josie Duffy, John Creuzot, Mark Gonzalez, and Margaret Moore |

Gonzalez failed to answer the question directly, conflating magistration with plea bargaining and insisting that his office was more fair than his predecessor.

Moore also talked around the issue, but in essence said she didn't think providing counsel at bail hearings was necessary. Prosecutors don't even attend those hearings in Travis County, she declared, an assertion which Grits found dubious. After all, the county indigent defense plan anticipates prosecutors may "fil[e] an application" with the court at magistration, while indigent defendants may apply for an attorney at that point, but don't get one until later. Moore suggested that a post hoc bail-review hearing was sufficient to protect defendants' liberty interests.

Creuzot was the only DA who said, definitively, "Yes," defense attorneys should be provided at magistration. He blamed Dallas judges who appealed the federal injunction for blocking the move, although at least one judge supports the idea. (The county commissioners court, which would have to come up with money to pay for additional defense counsel, surely also is a barrier to implementing that idea.)

Grits found this discussion dissatisfying, given recent developments in Texas bail-reform litigation.

In Galveston, in particular, a recent federal-court injunction explicitly required the county to provide attorneys at magistration. This was not mentioned.

Harris County eliminated magistration in 85 percent of misdemeanor cases to avoid having to make individualized determinations, and launched a pilot program to provide a public defender at bail hearings for the other 15 percent.

In Dallas, a federal judge said magistrates couldn't rely on a pre-set bail schedule without considering individual circumstances. Articulating those, of course, is a defense attorney's job. The injunction has been appealed, but the judge's order would require these hearings to occur within 48 hours of arrest.

So, if we're reading tea leaves here, in all three jurisdictions, federal judges have said that non-individualized bail hearings are unacceptable and that release decisions must be made promptly.

In that light, claims that it's sufficient to review non-individualized bail decisions later, as DA Moore declared, strike me as optimistic, at best. All the federal court rulings in Texas so far have required more.

Certainly it's insufficient to address the issue during plea bargaining, as Mark Gonzalez maintained! Part of the problem with excessive pretrial detention is that it makes defendants more likely to accept unfavorable plea bargains.

The US constitution forbids "excessive bail," not bail per se, so it's unlikely federal courts will ever "abolish money bail," as most #cjreform advocates would prefer. But it also seems clear to this observer that federal courts will eventually require individualized bail determinations, likely at magistration.

We've now seen three different options emerge from federal courts for how to do that: Provide counsel at magistration, as in Galveston; hold individualized hearings within 48 hours of arrest, as in Dallas; or simply eliminate bail determination hearings for most nonviolent cases, and provide lawyers at magistration for the remaining subset, as Harris County is doing.

No one can tell which of these options will be required writ large across Texas until the 5th Circuit rules in one of these cases. Now that the Harris County suit has settled, it seems likely that Dallas will be the first to reach that stage. Their preliminary injunction came out more than a year ago, while Galveston's only emerged last month.

Regardless, Creuzot was the only DA on the so-called "progressive prosecutor" panel who gave what Grits would consider a "progressive" answer on bail reform. Letting folks sit around in jail because they're too poor to pay just isn't good enough, anymore.

Labels:

bail,

Dallas County,

federal judges,

Harris County,

Nueces County

Friday, September 13, 2019

Needless shooting shows why cops shouldn't be first response to mental health calls

In the wake of the City of Austin funding an alternative approach to mental-health first response featuring mental-health clinicians taking the lead instead of cops, video has emerged from Corpus Christi of a police officer gunning down a mentally ill man wielding a metal pipe at point blank range. The victim didn't die, thankfully, but this was unnecessary:

Labels:

Mental health,

Nueces County,

Police,

use of force

Tuesday, November 28, 2017

Keep expectations realistic vis a vis 'reformer' DAs

In the world of criminal-justice reform, because there are so many different participants and levels of government involved in how the system operates, reformers must keep available a full tool chest of possible approaches, selecting each one to accomplish a particular task in a given situation.

For example, if you want to eliminate money bail, maybe litigation is the only option. OTOH, if one wants to close prisons, that must be done through the Legislature, and in particular the House Appropriations and Senate Finance Committees. Want to oppose local jail expansion? You'll need to lobby the county commissioners court. Or if one wants fewer people shot by police, the policies governing use of force are controlled by unelected administrators at local departments, with only indirect input from city managers or city councils. Each of these issues requires reformers to adopt a tailored approach if they hope to succeed; there's no one tactic which will transform the entire process.

Lately, it has become fashionable to claim that prosecutors are primarily or at least disproportionately to blame for mass incarceration, a view to which Grits only partially subscribes. But the principle champions of this critique have not developed viable visions for how prosecutors' offices might operate in the alternative. And so, the go-to move in the near term has been to run "reformer" DA candidates against incumbents, hoping a change at the top will trickle down throughout the agency.

However, using the electoral process to oust a DA is an expensive and difficult tool to employ among the array of possible options, and in many cases it may have limited practical utility. In some cases it can easily backfire. How can one tell if it's worth it?

Indeed, is it worth it at all? In a post responding to Josie Duffy Rice titled "'The Myth of the Progressive Prosecutor,'" Grits recently argued that, "Any differences between electeds play out at the margins of just a handful of individual cases. But the overarching structure and purpose of the institution inevitably remains undisturbed. Even when DAs take a progressive step, there are almost always pragmatic, internal reasons for it."

That flies in the face of expectations of reform supporters who back DA challenger candidates. Rice's colleague, Carimah Townes, recently examined the brief tenure of Nueces County DA Mark Gonzalez through the lens of a Disappointed Reformer, but it's unclear what exactly he was expected to do which would have pleased his critics.

Sure, Gonzalez could simply stop taking drug cases or use his discretion more radically to reduce local jail populations and prison commitments. But to expect him to do so is to expect things he never promised during his campaign.

Which brings us to what he did campaign on, and what reformers may reasonably expect from successful electoral strategies, particularly in the South. (Caveat: The new DA in Philadelphia appears to have a more visionary agenda, and I'm interested to see how he fares and exactly what he does differently from his predecessors. But none of our "reformer" Texas DAs promised anything close to his campaign platform.)

During the election, Gonzalez touted his own background as a proud defense attorney and Mexican-American motorcycle enthusiast. In addition, the remarkable "Not Guilty" tattoo across his chest gave voters an impression he would approach the job with a different sensibility. But the job is the job, as Grits argued in response to Ms. Rice's column. As long as decisions are being made within traditional frameworks - just by different lawyers - mostly the same outcomes will be reached, with a few differences at the margins whose importance will be magnified by the media beyond their real weight.

So why would one bother with an electoral strategy if that's the best outcome that can be expected? Generally, it's because the incumbent is so zealously "tough on crime" that it clouds their judgment and perspective. That was the case with Gonzalez's predecessor Mark Skurka. It was the case with the predecessors of Craig Watkins in Dallas and Nico Lahood in San Antonio (though both of those men later turned out to present their own problems). The ouster of John Bradley in Williamson County had important ripple effects throughout the state, even though his replacement turned out to be no great shakes and lost when she ran for re-election.

Kim Ogg in Houston is the exception to the only-a-bad-prosecutor trend. Her predecessor Devon Anderson was, relatively speaking, a reformer-Republican, though not as outspoken as Ogg. Her ouster resulted primarily from a partisan sweep that also saw all the judicial races flip and Hillary Clinton carry the county.

In Dallas, the Democratic primary race between John Creuzot and Elizabeth Frizell, who are competing for the right to take on Faith Johnson in November 2018, has taken on an establishment vs. reformer tone, with Creuzot (who switched parties to keep his judgeship, then switched back when Dallas turned blue) featured as an establishment foil, and Frizell as the ostensible resistance candidate. But Frizell's pitch, like Mark Gonzalez's, at the end of the day is incredibly general:

Which brings me to why our friends at the Fair Punishment Project are inevitably disappointed when they see the elected DAs they supported in action: They've sometimes projected more reformist heft onto these candidates than their campaign rhetoric ever justified, which really isn't the candidates' fault.

Mass incarceration is not a partisan issue and replacing an R with a D, or vice versa, doesn't change much regarding how the justice system operates.

For most of these reformer DA campaigns, and certainly for Gonzalez's, the big pitch was "I'm less of an asshole than the guy who has the job now." IMO, only when that is reason enough - i.e., when the incumbent is so much more actively harmful than is typical that simply removing them from power would improve outcomes - is an electoral strategy justified. That's because such elections can send a political message to pols about voter preferences that other politicians, like state legislators, will notice and heed.

But with less egregious cases, unless one is very clear-eyed regarding the import of potential achievements (e.g., "getting rid of Mark Skurka is a good thing," which it is), electoral strategies targeting DAs will mostly result in disappointment in terms of reducing mass incarceration.

Don't say you weren't warned.

|

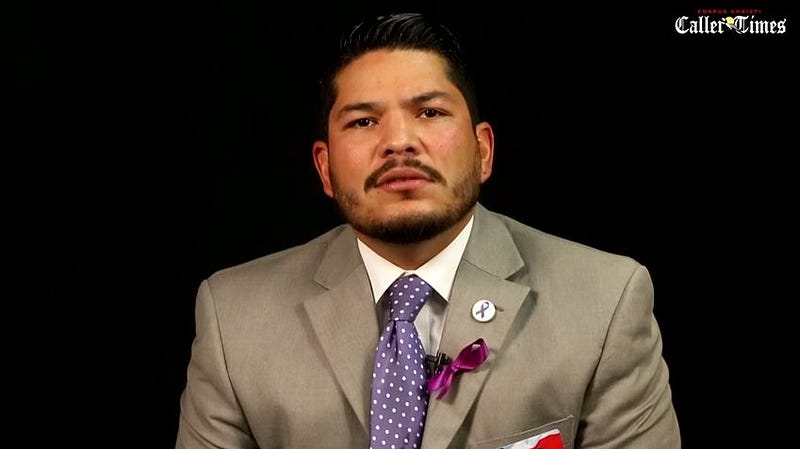

| Nueces County DA Mark Gonzalez |

Lately, it has become fashionable to claim that prosecutors are primarily or at least disproportionately to blame for mass incarceration, a view to which Grits only partially subscribes. But the principle champions of this critique have not developed viable visions for how prosecutors' offices might operate in the alternative. And so, the go-to move in the near term has been to run "reformer" DA candidates against incumbents, hoping a change at the top will trickle down throughout the agency.

However, using the electoral process to oust a DA is an expensive and difficult tool to employ among the array of possible options, and in many cases it may have limited practical utility. In some cases it can easily backfire. How can one tell if it's worth it?

Indeed, is it worth it at all? In a post responding to Josie Duffy Rice titled "'The Myth of the Progressive Prosecutor,'" Grits recently argued that, "Any differences between electeds play out at the margins of just a handful of individual cases. But the overarching structure and purpose of the institution inevitably remains undisturbed. Even when DAs take a progressive step, there are almost always pragmatic, internal reasons for it."

That flies in the face of expectations of reform supporters who back DA challenger candidates. Rice's colleague, Carimah Townes, recently examined the brief tenure of Nueces County DA Mark Gonzalez through the lens of a Disappointed Reformer, but it's unclear what exactly he was expected to do which would have pleased his critics.

Sure, Gonzalez could simply stop taking drug cases or use his discretion more radically to reduce local jail populations and prison commitments. But to expect him to do so is to expect things he never promised during his campaign.

Which brings us to what he did campaign on, and what reformers may reasonably expect from successful electoral strategies, particularly in the South. (Caveat: The new DA in Philadelphia appears to have a more visionary agenda, and I'm interested to see how he fares and exactly what he does differently from his predecessors. But none of our "reformer" Texas DAs promised anything close to his campaign platform.)

During the election, Gonzalez touted his own background as a proud defense attorney and Mexican-American motorcycle enthusiast. In addition, the remarkable "Not Guilty" tattoo across his chest gave voters an impression he would approach the job with a different sensibility. But the job is the job, as Grits argued in response to Ms. Rice's column. As long as decisions are being made within traditional frameworks - just by different lawyers - mostly the same outcomes will be reached, with a few differences at the margins whose importance will be magnified by the media beyond their real weight.

So why would one bother with an electoral strategy if that's the best outcome that can be expected? Generally, it's because the incumbent is so zealously "tough on crime" that it clouds their judgment and perspective. That was the case with Gonzalez's predecessor Mark Skurka. It was the case with the predecessors of Craig Watkins in Dallas and Nico Lahood in San Antonio (though both of those men later turned out to present their own problems). The ouster of John Bradley in Williamson County had important ripple effects throughout the state, even though his replacement turned out to be no great shakes and lost when she ran for re-election.

Kim Ogg in Houston is the exception to the only-a-bad-prosecutor trend. Her predecessor Devon Anderson was, relatively speaking, a reformer-Republican, though not as outspoken as Ogg. Her ouster resulted primarily from a partisan sweep that also saw all the judicial races flip and Hillary Clinton carry the county.

In Dallas, the Democratic primary race between John Creuzot and Elizabeth Frizell, who are competing for the right to take on Faith Johnson in November 2018, has taken on an establishment vs. reformer tone, with Creuzot (who switched parties to keep his judgeship, then switched back when Dallas turned blue) featured as an establishment foil, and Frizell as the ostensible resistance candidate. But Frizell's pitch, like Mark Gonzalez's, at the end of the day is incredibly general:

Frizell said her experience was different that that of Creuzot, who was a judge and prosecutor when Republicans controlled Dallas County politics.

"It's hard to do that when you came up in an era when prosecutors were not reform-minded," she said, adding that she would be a better choice to deal with bail reform and community concerns over police shootings.That's a promise to have a subtle difference in perspective on the part of the agency's top decision maker, but it's not a promise for radical, progressive reform. She says she'll be "better" on these issues, but doesn't specifically say what she'd do differently.

Which brings me to why our friends at the Fair Punishment Project are inevitably disappointed when they see the elected DAs they supported in action: They've sometimes projected more reformist heft onto these candidates than their campaign rhetoric ever justified, which really isn't the candidates' fault.

Mass incarceration is not a partisan issue and replacing an R with a D, or vice versa, doesn't change much regarding how the justice system operates.

For most of these reformer DA campaigns, and certainly for Gonzalez's, the big pitch was "I'm less of an asshole than the guy who has the job now." IMO, only when that is reason enough - i.e., when the incumbent is so much more actively harmful than is typical that simply removing them from power would improve outcomes - is an electoral strategy justified. That's because such elections can send a political message to pols about voter preferences that other politicians, like state legislators, will notice and heed.

But with less egregious cases, unless one is very clear-eyed regarding the import of potential achievements (e.g., "getting rid of Mark Skurka is a good thing," which it is), electoral strategies targeting DAs will mostly result in disappointment in terms of reducing mass incarceration.

Don't say you weren't warned.

Labels:

District Attorneys,

ideology,

Nueces County

Monday, October 31, 2016

Police pension bailouts, dreaming of Oklahoma, and other nightmarish scenarios on Halloween

A few things, while I've got you:

Lab delays spur boost in Nueces Co. personal bond use

In Corpus Christi, prosecutors have enacted a standardized policy of offering personal bonds to defendants charged in synthetic marijuana cases, mainly because of crime lab delays. The most likely reason for the shift: "The time it takes to get test results on the substances has been longer than the maximum allowed sentences. Possessing synthetic marijuana is a class B misdemeanor punishable by up to six months in jail. Test results from the Department of Public Safety labs have been taking about nine months to a year to get back." They should keep close track of outcomes with these defendants, it will create a natural experiment to compare them with defendants convicted before they changed the policy.

With the chairmen of the House Criminal Jurisprudence and Calendars Committees both residing in Nueces, perhaps this news will place more pressure on the Lege to either adequately fund crime labs or adjust sentences to reduce pressure on them. Honestly, the whole crime lab system - at DPS and otherwise - is at the breaking point. Numerous disciplines have come under attack as fundamentally non-scientific, and even disciplines like toxicology with a more sound scientific basis are overwhelmed by volume and undercut by attempts to perform them on the cheap, as evidenced by the following item.

News flash: Bad field tests cause false drug convictions (and not just in Houston)

ProPublica has a great piece on the use of scientifically flawed "field tests" for drugs used in Las Vegas, NV, following up on important NY Times coverage earlier this year of the use of the same type of $2 tests in Houston. Both are must-read pieces of journalism for anyone interested in the topic. In Houston, this topic plays directly into debates in the DA's race over racial disparities in drug enforcement, as 59 percent of defendants falsely accused and convicted based on false positive from cheap field tests were black. They also pump up the state's "exoneration" numbers, ensuring that Texas will lead the nation in disproven false convictions for years to come just based on what's come out of Houston alone. The thing is, we know that EVERYONE who uses these field tests likely accuse innocent people, not just those in Houston or Vegas. These stories show us the tip of a much larger iceberg.

Requests for police pension bailouts pit cops vs. anti-tax conservatives

Increasingly it's clear that police pensions are a latent but fully primed flash point between anti-taxation Republicans in the Legislature, more liberal city councils, and local police unions. In Dallas, the pension us oversubscribed with too-generous benefits, has engaged in a series of flawed, risky real estate deals, and is losing money hand over fist. The fund in Houston isn't much better. In those and ten other Texas cities, local control of police and fire pensions has been wrested away by the Legislature and vested into independent bodies on which cities have a voice but unions (and the Lege) have ultimate control. Lately, the Laura and John Arnold Foundation's Josh McGee has been pounding away at the fundamental fiscal insolvency of these funds, mos recently in this excellent short report written with Paulina Diaz on the Dallas police and firefighters' pension. Their bottom line assessment of the crisis in Dallas: "The city’s public pension debt has doubled in less than two years due to inadequate funding, irresponsible benefit enhancements, and poor investment decisions. The total unfunded liability is now at least $4 billion—and the plans do not have enough money to pay for nearly half of the retirement benefits workers have already earned."

All these pension funds want bailouts either from local or state taxpayers, putting the police and firefighters unions directly in conflict with low-or-no-tax conservatives around the state, not just in the Tea Party wing of the GOP but also among establishment Chamber of Commerce types who abhor large tax hikes. Police and firefighters are among the last employees who receive defined benefit pensions instead of defined contributions (typically in 401ks) like most everybody else. They'll claim the sky will fall if that's changed, but the truth is, as the Arnold Foundation report ably demonstrates, the sky will fall if nothing changes. MORE: The Texas Public Policy Foundation is holding an event on public employee pensions in Austin next week.

Dreaming of Oklahoma, and other unlikely scenarios

Grits never thought the day would come when I could write this, but part of me is a little envious of Oklahoma, or I should say Oklahoma reformers. They've put drug sentencing reductions on the ballot and therefore can have a conversation about the idea's merits directly with the voters instead of filtering reform through the legislative process, with the resulting compromises, delays and special-interest interventions that inevitably entails. OTOH, Grits was doing this work in the '90s, so I can remember an era when I was quite grateful Texas didn't have initiative and referendum. The tough-on-crime crowd could and would have proposed, and voters would likely have passed, much worse stuff, even, than actually got through, except in a venue where opponents have had no way to oppose, modify, counter or coopt the details of the proposals.

So while the prospect of ballot initiatives is tempting - and while part of me wishes we could similarly test Texas voters' views on criminal justice reform more directly than just polling, which generally shows support for the main reforms presently on the table, but whose results haven't been tested by the gauntlet of special-interest attacks which face a ballot initiative of this sort - I'm still glad Texas doesn't have initiative and referendum and would oppose it here if it were seriously suggested. If I were in Oklahoma, though, right about now I'd be busting my hump to help Questions 780 and 781 pass. Good luck to them.

Piling onCCA CoreCivic

In response to federal prison contracts being rescinded and surprisingly successful divestment campaigns aimed at reducing their capital, Corrections Corporation of America, the private prison operator, has rebranded and renamed itself as CoreCivic. According to this source, "Last month, CCA fired 12 percent of its corporate workforce to deal with sharply dropping investment—largely thanks to growing pressure campaigns to divest from private prisons." Here's the company's press release. Not to pile on, but I should mention several of the private prison facilities Grits has argued should be prioritized for closure by the Texas Legislature in 2017 areCCA CoreCivic units.

Lab delays spur boost in Nueces Co. personal bond use

In Corpus Christi, prosecutors have enacted a standardized policy of offering personal bonds to defendants charged in synthetic marijuana cases, mainly because of crime lab delays. The most likely reason for the shift: "The time it takes to get test results on the substances has been longer than the maximum allowed sentences. Possessing synthetic marijuana is a class B misdemeanor punishable by up to six months in jail. Test results from the Department of Public Safety labs have been taking about nine months to a year to get back." They should keep close track of outcomes with these defendants, it will create a natural experiment to compare them with defendants convicted before they changed the policy.

With the chairmen of the House Criminal Jurisprudence and Calendars Committees both residing in Nueces, perhaps this news will place more pressure on the Lege to either adequately fund crime labs or adjust sentences to reduce pressure on them. Honestly, the whole crime lab system - at DPS and otherwise - is at the breaking point. Numerous disciplines have come under attack as fundamentally non-scientific, and even disciplines like toxicology with a more sound scientific basis are overwhelmed by volume and undercut by attempts to perform them on the cheap, as evidenced by the following item.

News flash: Bad field tests cause false drug convictions (and not just in Houston)

ProPublica has a great piece on the use of scientifically flawed "field tests" for drugs used in Las Vegas, NV, following up on important NY Times coverage earlier this year of the use of the same type of $2 tests in Houston. Both are must-read pieces of journalism for anyone interested in the topic. In Houston, this topic plays directly into debates in the DA's race over racial disparities in drug enforcement, as 59 percent of defendants falsely accused and convicted based on false positive from cheap field tests were black. They also pump up the state's "exoneration" numbers, ensuring that Texas will lead the nation in disproven false convictions for years to come just based on what's come out of Houston alone. The thing is, we know that EVERYONE who uses these field tests likely accuse innocent people, not just those in Houston or Vegas. These stories show us the tip of a much larger iceberg.

Requests for police pension bailouts pit cops vs. anti-tax conservatives

Increasingly it's clear that police pensions are a latent but fully primed flash point between anti-taxation Republicans in the Legislature, more liberal city councils, and local police unions. In Dallas, the pension us oversubscribed with too-generous benefits, has engaged in a series of flawed, risky real estate deals, and is losing money hand over fist. The fund in Houston isn't much better. In those and ten other Texas cities, local control of police and fire pensions has been wrested away by the Legislature and vested into independent bodies on which cities have a voice but unions (and the Lege) have ultimate control. Lately, the Laura and John Arnold Foundation's Josh McGee has been pounding away at the fundamental fiscal insolvency of these funds, mos recently in this excellent short report written with Paulina Diaz on the Dallas police and firefighters' pension. Their bottom line assessment of the crisis in Dallas: "The city’s public pension debt has doubled in less than two years due to inadequate funding, irresponsible benefit enhancements, and poor investment decisions. The total unfunded liability is now at least $4 billion—and the plans do not have enough money to pay for nearly half of the retirement benefits workers have already earned."

All these pension funds want bailouts either from local or state taxpayers, putting the police and firefighters unions directly in conflict with low-or-no-tax conservatives around the state, not just in the Tea Party wing of the GOP but also among establishment Chamber of Commerce types who abhor large tax hikes. Police and firefighters are among the last employees who receive defined benefit pensions instead of defined contributions (typically in 401ks) like most everybody else. They'll claim the sky will fall if that's changed, but the truth is, as the Arnold Foundation report ably demonstrates, the sky will fall if nothing changes. MORE: The Texas Public Policy Foundation is holding an event on public employee pensions in Austin next week.

Dreaming of Oklahoma, and other unlikely scenarios

Grits never thought the day would come when I could write this, but part of me is a little envious of Oklahoma, or I should say Oklahoma reformers. They've put drug sentencing reductions on the ballot and therefore can have a conversation about the idea's merits directly with the voters instead of filtering reform through the legislative process, with the resulting compromises, delays and special-interest interventions that inevitably entails. OTOH, Grits was doing this work in the '90s, so I can remember an era when I was quite grateful Texas didn't have initiative and referendum. The tough-on-crime crowd could and would have proposed, and voters would likely have passed, much worse stuff, even, than actually got through, except in a venue where opponents have had no way to oppose, modify, counter or coopt the details of the proposals.

So while the prospect of ballot initiatives is tempting - and while part of me wishes we could similarly test Texas voters' views on criminal justice reform more directly than just polling, which generally shows support for the main reforms presently on the table, but whose results haven't been tested by the gauntlet of special-interest attacks which face a ballot initiative of this sort - I'm still glad Texas doesn't have initiative and referendum and would oppose it here if it were seriously suggested. If I were in Oklahoma, though, right about now I'd be busting my hump to help Questions 780 and 781 pass. Good luck to them.

Piling on

In response to federal prison contracts being rescinded and surprisingly successful divestment campaigns aimed at reducing their capital, Corrections Corporation of America, the private prison operator, has rebranded and renamed itself as CoreCivic. According to this source, "Last month, CCA fired 12 percent of its corporate workforce to deal with sharply dropping investment—largely thanks to growing pressure campaigns to divest from private prisons." Here's the company's press release. Not to pile on, but I should mention several of the private prison facilities Grits has argued should be prioritized for closure by the Texas Legislature in 2017 are

Monday, September 05, 2016

Mark Skurka's passive-aggressive Davy Crockett impression

Nueces County DA Mark Skurka, having been ousted by voters in his primary and facing lame duck status, has clearly entered his "To hell with all y'all, I don't give a f&%$" phase.

Regular readers may recall that, in early 2012, then-Gov. Perry's Criminal Justice Division deployed new rules governing the timeline by which counties must submit data on court cases, penalizing them for noncompliance by taking away federal grants if they refused to submit data in a timely manner. (See Grits coverage here, here, here, and here, and coverage of the state auditor's report that inspired the rule.).

In Nueces County, they've run up against a unique problem: The DA refuses to dismiss low-level misdemeanor cases which aren't being prosecuted and thus the county can't meet the normally generous reporting deadline for finalizing cases. At the Corpus Christi Caller-Times, Krista Torralva reported that, "Nueces County was denied $142,000 in grants and is at risk of losing about $1 million in all." Now, "The five county courts at law and eight state district courts have until Oct. 1 to resolve more than 400 cases from between 2010-2014. The Governor's Criminal Justice Division granted Nueces County a 60-day extension from Aug. 1 to get in compliance."

Skurka appeared uninterested in helping the county solve its grant problem, though grants include "funding for GPS monitors with victim notification in domestic violence cases." Already, "More than $142,000 in grants were denied to fund drug court for juvenile offenders, drunken driving court for adult offenders, security cameras for the courthouse and electronics systems." State district judges at the meeting, who normally oversee felony cases

Reading between the lines, this comes off as a final "FU" from an embittered pol aimed at his peers and the electorate, neither of whom appear particularly sorry to see him go. It's sort of a passive-aggressive version of Davy Crockett's declaration to the voters in Tennessee after losing his Congressional seat: "You can all go to hell and I shall go to Texas." By contrast, we likely won't see I don't care if you lose your stupid grant money emblazoned on t-shirts and swag. Whoever replaces Skurka will no doubt put this ignoble, spite-based behavior to rest and seek to work with the courts more productively. For the next few months, though, Nueces judges and court staff are left with a partner on these questions with no incentive to cooperate and who doesn't seem to care about them, their opinions, nor stewardship of county faith and funds. Ain't democracy grand?

Regular readers may recall that, in early 2012, then-Gov. Perry's Criminal Justice Division deployed new rules governing the timeline by which counties must submit data on court cases, penalizing them for noncompliance by taking away federal grants if they refused to submit data in a timely manner. (See Grits coverage here, here, here, and here, and coverage of the state auditor's report that inspired the rule.).

In Nueces County, they've run up against a unique problem: The DA refuses to dismiss low-level misdemeanor cases which aren't being prosecuted and thus the county can't meet the normally generous reporting deadline for finalizing cases. At the Corpus Christi Caller-Times, Krista Torralva reported that, "Nueces County was denied $142,000 in grants and is at risk of losing about $1 million in all." Now, "The five county courts at law and eight state district courts have until Oct. 1 to resolve more than 400 cases from between 2010-2014. The Governor's Criminal Justice Division granted Nueces County a 60-day extension from Aug. 1 to get in compliance."

Skurka appeared uninterested in helping the county solve its grant problem, though grants include "funding for GPS monitors with victim notification in domestic violence cases." Already, "More than $142,000 in grants were denied to fund drug court for juvenile offenders, drunken driving court for adult offenders, security cameras for the courthouse and electronics systems." State district judges at the meeting, who normally oversee felony cases

offered to take misdemeanor cases from the five county courts at law to quickly relieve them. But District Attorney Mark Skurka said that presented an issue because the misdemeanor prosecutors can't be in two places at once.Instead, the DA's office wants convictions out of these old cases:

[Judge David] Stith suggested the judges hire temporary special prosecutors to handle cases. But it would be nearly impossible for the two-person witness office to get all the witnesses together, Skurka said.

[Judge Sandra] Watts asked Skurka for his suggestion. He didn't offer one.

Assistant District Attorney Lorena Whitney suggested reaching plea agreements in cases of marijuana possession, driving with a suspended license and criminal trespass, which make up a large chunk of the pending misdemeanors.It should be mentioned that Nueces is nearly alone in still struggling with this problem. Most other counties are able to comply with the rules and nobody but Mr. Skurka is balking over old pot and suspended license cases. The idea that Skurka's recalcitrance stems from a commitment to "justice" beggars belief. How does it serve justice to keep 400 people in limbo for years without a speedy trial? Or to divert judges from felony courts that hear rape, robbery and murder cases to handle old misdemeanor leftovers? Dig deeper into these issues and Skurka loses hands down on the "justice" question.

Stith suggested dismissing cases that prosecutors weren't prepared to take to trial.

"See, that's the problem Judge," Skurka said. "You're trying to get these cases dismissed and that's not justice."

Hasette asked if the cases were worth prosecuting, especially in years-old cases in which witnesses haven't been located. Skurka suggested the witnesses weren't found because the judges hadn't set the cases for trial.

"Well we're about ready to set them," Watts said.

Reading between the lines, this comes off as a final "FU" from an embittered pol aimed at his peers and the electorate, neither of whom appear particularly sorry to see him go. It's sort of a passive-aggressive version of Davy Crockett's declaration to the voters in Tennessee after losing his Congressional seat: "You can all go to hell and I shall go to Texas." By contrast, we likely won't see I don't care if you lose your stupid grant money emblazoned on t-shirts and swag. Whoever replaces Skurka will no doubt put this ignoble, spite-based behavior to rest and seek to work with the courts more productively. For the next few months, though, Nueces judges and court staff are left with a partner on these questions with no incentive to cooperate and who doesn't seem to care about them, their opinions, nor stewardship of county faith and funds. Ain't democracy grand?

Labels:

crime data,

District Attorneys,

Grants,

Nueces County

Sunday, August 28, 2016

On interpreting meaning from Nueces DA ouster and the limitations of reform via prosecutor elections

The vanquishing of Nueces County DA Mark Skurka by a defense lawyer with "Not Guilty" tattooed across his chest was one of the prime examples offered up in a new academic article by Stanford's David Alan Sklansky titled, "The changing landscape for elected prosecutors." According to the article, Mark Gonzales was one of several prosecutors who have recently "won office by promising, in part, to reduce prosecutorial misconduct, excessive punishment, or overly aggressive, racially disproportionate police tactics." He "campaigned against overly aggressive prosecutions" and for "greater transparency." Here are the specific references to the Nueces County race:

None of this means Gonzales will be a shoo-in. He faces a Republican candidate and in 2012 Nueces County went for Romney. His best hope will be if Donald Trump inspires significant numbers of Republican voters to stay home. And even if he is elected, what meaning can one derive from it? You can argue Democratic primary voters were making a statement, but if Gonzales loses in the general along partisan lines, would that be a pro or anti-reform statement? Neither, really. It just means partisanship outweighs nearly every issue in the minds of general election voters, which is hardly news.

While attempting to rebut arguments that prosecutor elections are poor vehicles for reformist aspirations, Sklansky does recognize the "limitations" on elections' ability to hold DAs accountable:

In February 2016 [sic], the incumbent District Attorney in Nueces County, Texas, Mark Skurka, lost his primary race to Mark Gonzales, a defense attorney who lacked prosecutorial experience and had “not guilty” tattooed across his chest; Gonzales had promised greater transparency and a crackdown on prosecutorial misconduct.Here's a bit more detail:

In March 2016, in what local media called “a huge upset,” the well-known District Attorney of Nueces County, Texas, career prosecutor Mark Skurka, was turned out of office in the Democratic Primary. Skurka lost to Mark Gonzalez, a longtime criminal defense attorney with no prosecutorial experience with “not guilty” tattooed across his chest. During the campaign, Gonzalez embraced his identity as a hard-charging defense attorney. The principal issues on which he ran were prosecutorial misconduct and, in particular, the improper withholding of exculpatory evidence. He emphasized a string of cases in which convictions obtained in Nueces County had been overturned on appeal and the prosecutors had been accused of misconduct. Every prosecutor, Gonzales said, should have “not guilty” tattooed “on their heart,” because until convicted at trial, “everyone accused of a crime is not guilty.”In a preview of the Nueces DA race, Grits earlier noted that Skurka was "the hometown DA for the Democratic Chairman of the Texas House Criminal Jurisprudence Committee and the Republican Chairman of the House Calendars Committee, giving him out-sized political influence for a Democratic office holder." A significant scandal just weeks before the election probably helped seal the incumbent's fate. At 56-44, the race was pretty much a stomping.

None of this means Gonzales will be a shoo-in. He faces a Republican candidate and in 2012 Nueces County went for Romney. His best hope will be if Donald Trump inspires significant numbers of Republican voters to stay home. And even if he is elected, what meaning can one derive from it? You can argue Democratic primary voters were making a statement, but if Gonzales loses in the general along partisan lines, would that be a pro or anti-reform statement? Neither, really. It just means partisanship outweighs nearly every issue in the minds of general election voters, which is hardly news.

While attempting to rebut arguments that prosecutor elections are poor vehicles for reformist aspirations, Sklansky does recognize the "limitations" on elections' ability to hold DAs accountable:

Perhaps the most serious [limitation] is that voters generally are poorly positioned to assess the performance of an elected prosecutor. Prosecutors do much of their most important work not in open court but behind closed doors: that is they consult with police officers, make charging decisions, determine what evidence needs to be disclosed, and hammer out plea deals. And prosecutors’ offices tend to be secretive and opaque, far more so than even most police departments. So the public often lacks basic information about how a district attorney’s office is operating. Moreover, it isn’t even clear what information the public should want or should care most about; there is remarkably little consensus about what distinguishes good prosecutors’ offices from bad ones. It isn’t just that people disagree; most of us have, within ourselves, conflicting expectations for prosecutors. We want them to be zealous advocates and dispassionate ministers of justice; champions of justice and instruments of mercy; creatures of the law and exercisers of discretion. All of this —the lack of transparency, the disagreements and conflicting expectations about how prosecutors should do their jobs— makes it difficult to assess the ultimate significance of ... any of the election results we’ve been discussing.Real prosecutorial reform must extend beyond elections to the statehouse and the judiciary. But when the opportunity arises for voters to make a statement, it's encouraging to find that increasingly more and more are willing to do so.

Monday, April 25, 2016

Nueces jail overcrowding caused by pretrial detention

In Nueces County, the Sheriff is raising the alarm about jail overcrowding problems. But the reasons being suggested for high inmate numbers don't really explain things. "Some reasons for the spike include a reduced number of referrals to

medical facilities, increases in arrests for criminal trespass in the

new RTA building across from city hall and cases waiting to be presented

to a grand jury, said court administrator Marilee Roberts," according to a report in the Corpus Christi Caller Times (April 19).

A quick look at the latest Texas Commission on Jail Standards inmate population report from Nueces County shows that assessment was a misdiagnosis. Like most other crowded jails in the state, the real trouble in Nueces is excessive pretrial detention. A whopping 60.6 percent of Nueces jail inmates were incarcerated awaiting trial as of April 1st. Further, a full 22.5 percent of inmates are misdemeanor defendants incarcerated pretrial, compared to only 9.5 percent statewide.

By contrast, in April 2006 only 21.7 percent of Nueces jail inmates were incarcerated awaiting trial, and only 3.2 percent of Nueces County inmates were pretrial misdemeanor defendants. Nueces would have no jail overcrowding problem if they'd kept pretrial detention at those levels.

At this point, Nueces County has 4 percent of the state's incarcerated pretrial misdemeanants but only 1.3 percent of the state's population.

Jail overcrowding in Nueces County amounts to a self-inflicted wound. While some local officials want to use the situation to promote new jail construction, really what's needed is greater accountability for judges and prosecutors who're allowing the jail to be misused in this fashion.

A quick look at the latest Texas Commission on Jail Standards inmate population report from Nueces County shows that assessment was a misdiagnosis. Like most other crowded jails in the state, the real trouble in Nueces is excessive pretrial detention. A whopping 60.6 percent of Nueces jail inmates were incarcerated awaiting trial as of April 1st. Further, a full 22.5 percent of inmates are misdemeanor defendants incarcerated pretrial, compared to only 9.5 percent statewide.

By contrast, in April 2006 only 21.7 percent of Nueces jail inmates were incarcerated awaiting trial, and only 3.2 percent of Nueces County inmates were pretrial misdemeanor defendants. Nueces would have no jail overcrowding problem if they'd kept pretrial detention at those levels.

At this point, Nueces County has 4 percent of the state's incarcerated pretrial misdemeanants but only 1.3 percent of the state's population.

Jail overcrowding in Nueces County amounts to a self-inflicted wound. While some local officials want to use the situation to promote new jail construction, really what's needed is greater accountability for judges and prosecutors who're allowing the jail to be misused in this fashion.

Labels:

County jails,

Nueces County,

pretrial detention

Thursday, December 17, 2015

Nueces jailer who beat inmate, accused him of assaulting a public servant, faces no consequences

Here's a story that reminded me of the unheralded Carlos Flores exoneration, where a man pled guilty to assaulting an officer when really the officer had assaulted him, while handcuffed, and the police department had exculpatory video in its possession that it failed to turn over to prosecutors.

In Corpus Christi in August, reported Krista Torralva at the Caller Times (Aug. 12):

For prosecutors, though, that didn't mitigate what they'd seen on the videotape:

So far, though, the jailer has faced no reprisals, has not been charged with a crime, nor even been named publicly in news coverage. On September 11, Torralva reported that:

At least, unlike in the Carlos Flores case, prosecutors vetted the evidence and outed the jailer's assault before forcing Gonzales to plea bargain to a crime he didn't commit. Thank heaven for small blessings.

In Corpus Christi in August, reported Krista Torralva at the Caller Times (Aug. 12):

A Nueces County jailer who accused a former inmate of attacking him admitted video footage showed the inmate was the victim, according to a sheriff's office investigator's report.Though none of the newspaper's coverage names the jailer, to its credit, the Caller Times filed extensive open records requests regarding the incident and obtained video:

Prosecutors declined to move forward in June with a charge of assault on a public servant against the inmate, Danny Gonzales. Last week, a case against him involving another jailer in a separate incident in the jail was dismissed.

Video of the May 31 incident shows an officer open the door to Gonzales' cell. Gonzales approaches the officer and appears to say something to him. The officer then pushes Gonzales, pins him against the cell wall and wrestles him to the ground while another officer looks on. The second officer joins the first in forcing Gonzales to the ground and the two officers punch the inmate several times. At one point, the second officer pushes Gonzales' face against the ground. About six additional jailers respond as the incident ends. Two of the officers then lead Gonzales out of the cell.In addition:

The video, which lasted about three minutes, has no audio.

Both officers wrote in their reports that Gonzales swung at one of them when they tried to secure his left arm. The officer told a sheriff's office investigator that he placed his hand on Gonzales' arm to have him back up before Gonzales struck him, according to the investigator's report. The video does not show the officer placing a hand on Gonzales before charging him.

The investigator wrote that she had the officer watch the video and asked "if he still considered himself as the victim or if he felt that he assaulted" Gonzales.

"(Correctional Officer) stated that after viewing the video surveillance that Inmate Gonzales was the victim," the investigator wrote in the incident report.

Lorena Whitney, a chief prosecutor, cited the video when she declined to accept the case against the inmate.In the next day's paper (Aug. 13), Sheriff Jim Kaelin defended the jailer's action, and emphasized that the victim was somebody they'd frequently seen before. "Gonzales has a 2013 conviction for assaulting a public servant," the paper reported, and "Court records show he also has misdemeanor convictions including failing to identify himself as a fugitive, driving with an invalid license and for assaulting a family member. Gonzales was arrested last year for violating conditions of his probation."

"Video does not match what officers described as to what occurred before assault (and) during assault," Whitney wrote in a form rejecting the case dated June 11, five days before the investigator interviewed the officer.

For prosecutors, though, that didn't mitigate what they'd seen on the videotape:

District Attorney Mark Skurka said as a result his office is tightening its requirements of the jail to accept assault on public servant cases. He expects prosecutors will need video evidence in most cases of assaults on jailers or an explanation as to why video does not exist. He also wants any existing reports of prior or subsequent incidents involving the inmate and jailer.One wonders how many of those 30-40 cases per year have people who, like Gonzales, were in fact innocent of the charges?

Each year, the district attorney's office gets an estimated 30-40 cases from the jail involving assault on a public servant, Skurka said.

So far, though, the jailer has faced no reprisals, has not been charged with a crime, nor even been named publicly in news coverage. On September 11, Torralva reported that:

A Nueces County jailer shown hitting an inmate in a cell during a videotaped confrontation has been cleared of any wrongdoing through an internal investigation.In that story, we get this tidbit:

"His actions were justified and were not in violation of rules and policies," Nueces County Sheriff's Office Chief Deputy John Galvan said.

During a video taped interview with a sergeant before the internal affairs investigation one officer changed his account after watching video of the incident. The sergeant tells the officer his actions were inappropriate and asks him if he still feels like he is the victim, to which he answers "no."So the correctional officer admitted he was not the victim of an assault, as he'd claimed in an official report, and that in fact he'd assaulted the inmate. But the Sheriff's department cleared him of any wrongdoing, and so far the DA's office has not indicted him.

Twice, Sergeant Marilyn King asks the officer if he assaulted Gonzales. The officer answers "yes" both times.

"I don't feel like I was the victim," the officer said.

At least, unlike in the Carlos Flores case, prosecutors vetted the evidence and outed the jailer's assault before forcing Gonzales to plea bargain to a crime he didn't commit. Thank heaven for small blessings.

Labels:

County jails,

District Attorneys,

Nueces County,

testilying,

use of force,

video

Saturday, January 24, 2015

Is reticence of Nueces prosecutors to disclose evidence an institutional failure?

Grits had missed a story from earlier this month about the Nueces County DA allegedly withholding evidence in criminal cases. Reported the Corpus Christi Caller Times (Jan. 7):

The story also pointed to whistleblower litigation by "Eric Hillman, a former Nueces County prosecutor [who is] suing the county for wrongful termination. Hillman claims his bosses instructed him not to tell the defense team he found a witness who would help a man he was prosecuting." In addition, "three other defense attorneys sat in the courtroom gallery and were ready to testify Wednesday but weren’t called to the stand for time reasons."

It's hard to understand - aside from their general lameness and historical unwillingness to discipline prosecutors - how Mr. Hillman's allegations, or Judge Hernandez's ruling, in particular, wouldn't trigger a disciplinary review by the state bar against prosecutors in the office.

Defense lawyers lost the motion at the trial court level but simply exposing such stories to disinfecting sunlight has a salutary effect.

MORE: See additional background on the Hillman case.

The Nueces County District Attorney’s Office has shown a pattern of turning over evidence at the last minute and sometimes withholding it all together, defense attorneys testified Wednesday.In addition to that case, "In June, then 105th District Judge Angelica Hernandez found prosecutors withheld evidence and acted in bad faith in a child endangerment case," the paper reported.

Attorneys for Trinity Ringelstein, who is serving a life sentence, argued prosecutors waited until the week before his capital murder trial to give them tapes containing more than 72 hours of phone conversations he had while in the Nueces County Jail.

Ringelstein was first arrested in 2012 on suspicion of fatally shooting Micah Seth Horn, 23, near a park in the 1000 block of Harbor Lights Drive. After a three-week trial, Ringelstein was convicted and sentenced to life in prison last year.

The law requires prosecutors to hand over evidence in a timely manner.

During the daylong hearing his attorneys sought to prove prosecutors have delayed turning over key evidence in several other felony cases.

District Attorney Mark Skurka, who did not attend the hearing, disputed the claims in a statement to the Caller-Times.

“The District Attorney’s Office provides evidence to the defense as required by law. We strongly deny these allegations,” Skurka said.

The story also pointed to whistleblower litigation by "Eric Hillman, a former Nueces County prosecutor [who is] suing the county for wrongful termination. Hillman claims his bosses instructed him not to tell the defense team he found a witness who would help a man he was prosecuting." In addition, "three other defense attorneys sat in the courtroom gallery and were ready to testify Wednesday but weren’t called to the stand for time reasons."

It's hard to understand - aside from their general lameness and historical unwillingness to discipline prosecutors - how Mr. Hillman's allegations, or Judge Hernandez's ruling, in particular, wouldn't trigger a disciplinary review by the state bar against prosecutors in the office.

Defense lawyers lost the motion at the trial court level but simply exposing such stories to disinfecting sunlight has a salutary effect.

MORE: See additional background on the Hillman case.

Labels:

Brady violations,

District Attorneys,

Nueces County

Thursday, January 22, 2015

Pretrial detention, not 'growth,' driving overincarceration at Nueces County Jail

Here's another Texas jail building proposal - this time out of Nueces County (Corpus Christi) - in which officials are claiming population growth is driving overincarceration. Reported KRIS-TV:

In July of 1995, the Nueces County jail population stood at 892, of which 222 (25 percent) were being detained pretrial. In July 2014, the total population stood at 1,042, with 645 (62 percent) of those being detained pretrial. (See historical reports since 1992 here.) By comparison, the total 1995 population in Nueces County was 310,435, and 352,107 in 2013, or a 13.4 percent increase, while the jail population grew at a slightly greater rate - 16.8 percent.

Looking more closely, though, the 1995 jail population figure is artificially inflated because the jail was full back then of convicted offenders awaiting transfer to TDCJ, an issue that's been largely resolved in the 21st century since the state-prison system tripled in size. There were 334 convicted felons in Nueces awaiting transfer to prison on July 1, 1995, and only 132 in July 2014. Adjusted to account for those, the remaining jail population grew more than 50 percent.

Virtually all of the difference in the Nueces County jail population is accounted for by increased pretrial detention, which as we've discussed vis a vis Kerr County is a policy decision by judges and prosecutors, not a function of "growth." And keep in mind this is a period when crime rates dramatically declined.

Finally, the Sheriff speculated that extra jail space "could be paid for in part by money that comes from housing federal inmates." Any fiction that the jail will pay for itself in the current, over-saturated Texas incarceration market must be snuffed: Ask voters in Lubbock or Waco how that story turns out!

Perhaps, when it's debated publicly, Nueces County voters will support the policy decision to incarcerate so many more people pretrial, including hundreds of misdemeanor defendants. Or maybe they'll think scarce jail resources should be deployed more frugally. But portraying the need as stemming from simple population growth misrepresents the demand for more beds, which results from choices by elected officials, not some cosmic inevitability because there are sooo many more criminals these days.

This is a critical time for the Nueces County Jail because it's now at 93% capacity.Once again, I've no doubt the jail is overcrowded, but let us not suffer the absurd declaration that it's overcrowded because "We are 20 years behind the growth of the city." Instead, let's review the facts.

"The jail has been overcrowded a number of years. When I say overcrowded we have almost reached our capacity," said Nueces County Sheriff Jim Kaelin.

The jail can hold 1,068 inmates. It's limited by law not to exceed 90-percent capacity in case more space is needed for problem inmates or if maintenance issue surface.

"We are 20 years behind the growth of the city and that is a long time for everything else to grow around you and for your jail not to grow," said Kaelin.

In July of 1995, the Nueces County jail population stood at 892, of which 222 (25 percent) were being detained pretrial. In July 2014, the total population stood at 1,042, with 645 (62 percent) of those being detained pretrial. (See historical reports since 1992 here.) By comparison, the total 1995 population in Nueces County was 310,435, and 352,107 in 2013, or a 13.4 percent increase, while the jail population grew at a slightly greater rate - 16.8 percent.

Looking more closely, though, the 1995 jail population figure is artificially inflated because the jail was full back then of convicted offenders awaiting transfer to TDCJ, an issue that's been largely resolved in the 21st century since the state-prison system tripled in size. There were 334 convicted felons in Nueces awaiting transfer to prison on July 1, 1995, and only 132 in July 2014. Adjusted to account for those, the remaining jail population grew more than 50 percent.

Virtually all of the difference in the Nueces County jail population is accounted for by increased pretrial detention, which as we've discussed vis a vis Kerr County is a policy decision by judges and prosecutors, not a function of "growth." And keep in mind this is a period when crime rates dramatically declined.

Finally, the Sheriff speculated that extra jail space "could be paid for in part by money that comes from housing federal inmates." Any fiction that the jail will pay for itself in the current, over-saturated Texas incarceration market must be snuffed: Ask voters in Lubbock or Waco how that story turns out!

Perhaps, when it's debated publicly, Nueces County voters will support the policy decision to incarcerate so many more people pretrial, including hundreds of misdemeanor defendants. Or maybe they'll think scarce jail resources should be deployed more frugally. But portraying the need as stemming from simple population growth misrepresents the demand for more beds, which results from choices by elected officials, not some cosmic inevitability because there are sooo many more criminals these days.

Labels:

County jails,

Nueces County,

pretrial detention

Friday, September 13, 2013

Probation revocations down, but not by much; re-arrest rates among DWI probationers plummets

More evidence that Texas' 2007 probation reforms perhaps contributed less than has been previously estimated to recent prison population declines. The main strategy of the 2007 reforms was to reduce probation and parole revocations to prison by incentivizing diversion and progressive sanctions programs. That's worked better on the parole side than for probation (aka "community supervision"). From the Dec. 2012 "Report to the Governor and Legislative Budget Board on the Monitoring of Community Supervision Diversion Funds" (pdf):

County-level probation revocation trends

By contrast, reducing probation revocations has been a tougher nut to crack, in part because of decentralized local control over the process among various counties and judges. Here are the relative increases and decreases for probation revocations among Texas' largest departments since just before Texas' much-vaunted probation reforms took effect:

This chart perhaps provides a better sense of relative county practices than the previous one. It compares probation populations and revocations among large counties as a proportion of their statewide total. (See this data for all counties in Appendix C to the report.) Counties in which the right-side number is significantly greater than the left-hand column may be considered more aggressive at revoking probationers than their peers. That differential is especially significant in massive Harris County because of the sheer volume they process. Tarrant's numbers here are especially striking, putting their paltry 4.3% decline from the earlier chart in context. Meanwhile, Travis, Hidalgo, and even Bexar don't appear nearly as problematic on this chart as they did in the first table.

Recidivism among probationers declining, especially DWI

According to the Dec. 2012 report, 71.7% of felony probationers revoked back to prison in FY2012 were convicted of nonviolent crimes - drug offenses (32.2%), property offenses (30.4%), and DWI (9.1%), with the rest coming from violent (17.9%) and other (10.4%) felony offenses.

Remarkably, and for the most part unheralded, recidivism rates for felony probationers have been declining. "The overall two-year re-arrest rate for the FY2005 sample was 34.4% (8,914 offenders). The overall two-year re-arrest rate for the FY2010 sample was 31.8% (8,811 offenders), which was a decrease from the FY2005 sample."

The drop in re-arrest rates for DWI offenders in those two studies was especially striking: 16.9% of the 2005 cohort was re-arrested compared to 11.5% of the 2010 cohort - a 32% drop! That's a success story nobody tells much. Re-arrest rates for probationers convicted of drug offenses declined 13% over this period; 10.6% for property offenders. But DWI stands out. Perhaps new treatment resources aimed at that group are helping.

Felony revocations to TDCJ in FY2012 represent a 2.8% decrease from FY2005 (677 fewer felony revocations) and a 1.8% decrease from FY2011 (432 fewer felony revocations). However, the percentage of revocations to TDCJ for a technical violation of community supervision conditions increased from 48.5% in FY2011 to 49.0% in FY2012.Those are essentially insignificant reductions given the scope of the decline in state prison populations witnessed over the last half decade.* Felony technical revocations among probationers declined 10.9% from 2005 to 2012, TDCJ reported, but they're still awfully high and that small decline was far out-paced by two factors on the parole side: Dramatically reduced parole revocations and marginally increased approval rates by the parole board. Both may be viewed as an expression of legislative policy. Reduced parole revocations stem from greater use of intermediate sanctions facilities (ISFs) and other diversion programs created after 2007. And higher approval rates, particularly for low-risk offenders, resulted in large part from the board finally edging closer to targets under non-binding release guidelines that the Lege mandated they create.

County-level probation revocation trends