The Wall Street Journal on Sunday

published an item reporting on a nationwide decline in misdemeanor arrests, a trend

this blog has been documenting for several years. So Grits thought it worth comparing the national trends cited to Texas data.

The WSJ article focused on jurisdictions where misdemeanor arrests could be broken out by race, with arrests of black people accounting for a disproportionate share of the decrease. Texas data don't immediately allow us to make similar, racially delineated analyses, but the overall trend of reduced misdemeanor cases holds for Texas.

Texas misdemeanor cases by the numbers

Looking at top-line stats from the

Office of Court Administration's 2018 Annual Statistical Report (from which all graphs below are screenshots), the number of non-traffic misdemeanor cases in Texas peaked in 2007 at 585,499, declining to 404,001.

When you consider Texas' dramatic population growth over these years, the decline appears even more significant.

Texas witnessed especially large declines over the previous five years in misdemeanor theft (-47%), theft by check (-81%), and driving with an invalid license (-25%), with small increases (less than population growth) for family violence (5%), marijuana possession (4%), and 1st offense DWI (2%).

Grits finds especially interesting the decline in misdemeanor-property-theft cases. Texas

raised property-theft thresholds in 2015, so that one must now steal $2,500 to be charged with a felony. Felony-theft cases predictably declined in response, but misdemeanor theft cases declined even more. Perhaps that's a function of cops being less willing to focus attention on low-level cases, the tuff-on-crime crowd will surely say. But both reported crime stats and the National Crime Victim Survey tell us property thefts declined throughout this period. So if police did de-prioritize them, then policing clearly wasn't having the crime deterring effect that traditional models might predict. In fact, if such "de-policing" occurred, it correlated with less theft, not more. This raises a counter-intuitive possibility:

Maybe what police do after the fact doesn't have that much to do with crime rates in the first place?

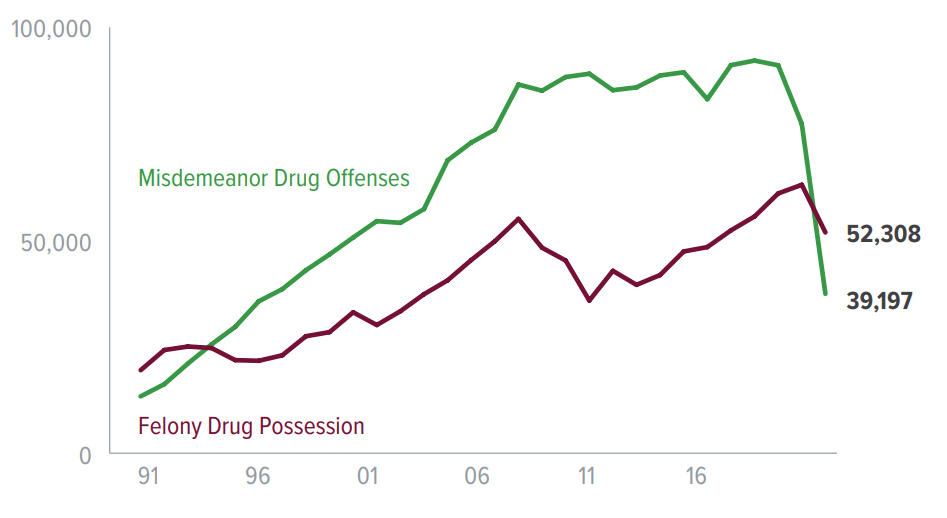

The 2018 data don't capture the period after the Texas Legislature accidentally made pot cases more difficult to prosecute without a lab test, but before then, both misdemeanor drug cases (mostly pot) and felony drug cases (mostly harder drugs) were a big source of growth in prosecutions:

Here's how new Texas misdemeanor and felony cases broke out in FY 2018:

The biggest decline, however, has been in traffic cases and other Class C misdemeanors, a trend which

this blog has documented in the past.

Delving more deeply into these Class Cs, every category except local traffic ordinances have declined over the last five years. (I'm curious if readers have any suggestions why enforcement of local traffic ordinances would increase by a third over the last five years while enforcement of state traffic laws declined?)

Moreover, juvenile Class C cases have plummeted, driven largely but not entirely by the state's decriminalization of truancy:

Reporters or policy makers who would like to replicate these data for their local area may use the

OCA's data query tool to break them out by jurisdiction.

What's going on?

So why is this happening? Some of the trends cited in the WSJ article don't apply to Texas - e.g., marijuana legalization or decrim hasn't happened here, and Texas' car-patrol-based policing doesn't see as frequent use of "stop and frisk" tactics as do jurisdictions where officers walk a beat.

The WSJ cited

FBI statistics to document "steady declines in disorderly conduct, drunkenness, prostitution and loitering violations," which arguably could be a function of the rise of smart phones, gaming, and internet culture. Much "disorderly conduct" now occurs online, much to the detriment of the political culture, while "loitering" these days may more frequently involve staring at a telephone. Similarly, prostitutes in 2019 are less likely to stand out on the street and more likely to respond to text messages or queries on a website.

Grits has written before about

declines in DWI and public drunkenness arrests, which I suspect may also related to the rise of car sharing apps that can easily get drunks off the streets or out of their own cars.

On Twitter, Grits asked a couple of national experts their opinions on sources of declines in misdemeanor arrests. Megan Stevenson, an economist and legal scholar at George Mason Univesity, suggested, "Broken windows policing going out of vogue. Gentrifying cities means poor people no longer live where rich people work. Increased surveillance technology reduces willingness to shoplift/graffiti. Lower blood lead levels in children." She also wondered if the trend may be influenced by "Shifting law enforcement to private security companies who intimidate but don’t arrest?"

And our pal Alexandra Natapoff, now of UC Irvine and author of

Punishment Without Crime, a book-length treatment of misdemeanor questions, suggested the trend might also relate to "changes in police arrest quota and promotion policies" or attempts to reduce "Jail costs."

Austin's

recent brouhaha over decriminalizing sitting, lying and camping in public spaces makes Grits give extra credence to Professor Stevenson's hypothesis about gentrifying cities removing poor people from the places rich folks live and work. Austin has always had a significant homeless population during the 34 years I've lived here. But as long as they were sleeping in creek beds and behind dumpsters where no one could see them, for most of the city's more affluent population, "out of sight, out of mind," was good enough. As soon as middle and upper class folks began to see homeless people in their daily lives - mostly under highway overpasses and in tents on roadsides - the weeping and gnashing of teeth began (with GOP officials at the local, state and national levels fanning the flames of discontent as vigorously as they could muster).

Grits considers these interesting suggestions, but all of them beg the question, why were misdemeanor arrests going up before 2007? After all, both reported and unreported low-level crime (as judged by the National Crime Victim Survey) has declined dramatically since the 1990s, and we didn't see arrest reductions until relatively recently.

Since we don't know why arrests continued to rise as crime declined, it's equally hard to tell why arrests went down as crime declined even more. For that matter, no one knows for sure why crime has declined in the first place. There are

many hypotheses.

In an era when economists have built out a sizable cottage industry developing Bayesian "causal inference" models that supposedly flesh out specific

causal relations for crime trends, in reality, nobody really understand the whys and wherefores of even the most basic tendencies of the justice system. Your correspondent has come to believe that running ever-more regression analyses on the same, extremely limited datasets is unlikely to cast more light on the subject.

Regardless of the cause, the

footprint of the Texas justice system has reduced dramatically over the last decade, even if prison populations

remain stubbornly high. These misdemeanor data provide further evidence of that trend and arguably played a big part in creating that outcome.

For my part, Grits considers the decline in misdemeanor arrests and cases mainly a positive development, not a problem to solve. Others' mileage may vary.

.jpg)